Canadian researchers are exploring whether diseases and other health problems can be prevented by taking a peek at DNA and setting out a diet for people in an emerging field known as nutrigenomics.

The science of measuring how genes in the body react to nutrients in foods is gaining popularity and a test designed for dieticians, called Nutrigenomix, has been developed at the University of Toronto.

That means you may be able to learn if you need more or less vitamin C or folic acid and whether too much salt or caffeine will negatively affect your genes, leaving you vulnerable to disease.

Dietician Doug Cook used the test on himself and learned his DNA doesn’t agree with salt, possibly increasing his risk for high-blood pressure later in life.

“Based on the results, I am cutting back more on sodium that I did before,” he said.

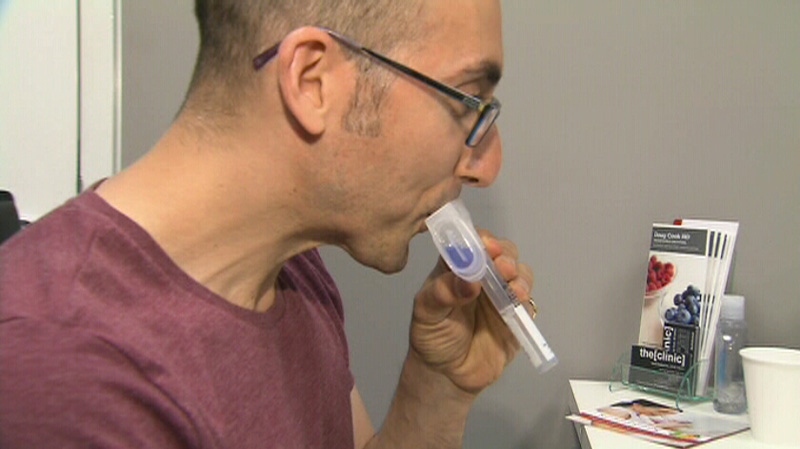

The Nutrigenomix test requires only a saliva sample and reveals how a person's unique genetic code determines their body's response to seven components of their diet.

The test kits were developed exclusively for the use of registered dietitians, since they are the most knowledgeable practitioners to deliver reliable nutrition advice.

Based on the results, a dietitian can guide a client to eat more - or less—of certain foods in order to decrease their risk of developing heart disease, diabetes, high blood pressure, obesity and related health conditions.

Dr. Ahmed El Sohemy, a researcher in the Department of Nutritional Sciences at the University of Toronto who helped develop the test says the response has exceeded his team’s expectations.

“We are receiving calls from dieticians from around the world,” he tells CTV News

While studies show many Canadians ignore advice from experts encouraging consumption of healthy food, some dietitians think such a DNA test might “scare” people into eating better.

“People hear about nutrition, they don’t act on the advice, but if they know they have certain genes, they are more likely to put it to practical use,” dietitian Rosie Schwartz told CTV News.

By next year, scientists hope to expand the test to be able to tell people if it’s in their genes to crave sugar or carbohydrates.

Artist Mark Gleberzon is a health-conscious person, but he craves caffeine.

He knows that studies have shown the stimulant in coffee and some soft drinks can increase the risk of heart attack in some, while actually protecting others.

“If ultimately I am going to live a better life, I’d rather know that,” he said.