Canada's health-care crisis: Who's accountable, and how can we fix an overburdened system?

This winter, two Nova Scotia communities were left reeling after two women, Charlene Snow and Allison Holthoff, died following lengthy emergency room waits in hospitals on opposite sides of the province.

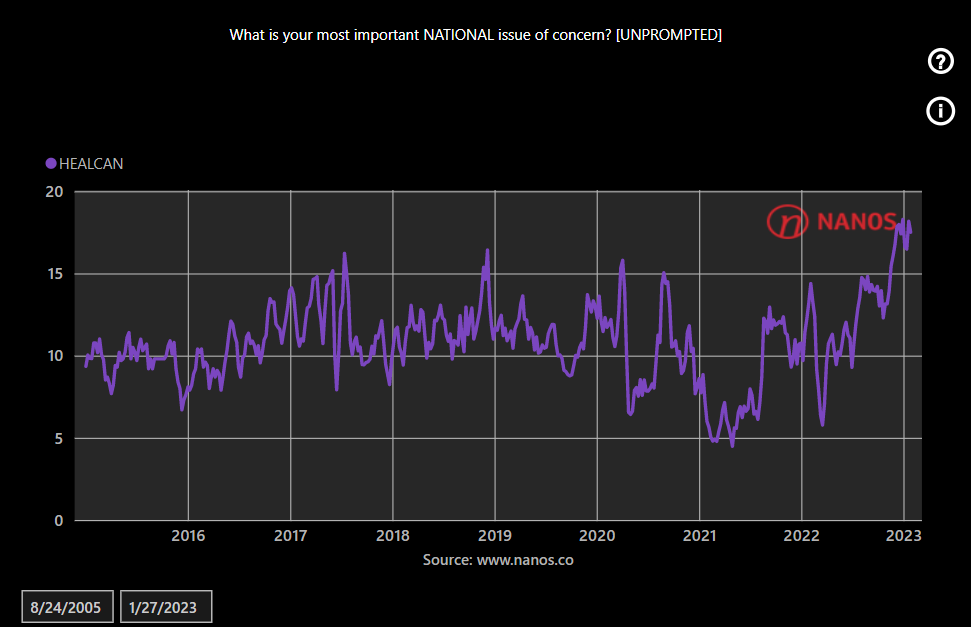

According to the latest weekly issue tracking by Nanos Research, more Canadians consider health care their biggest national concern now than at any point since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic.

As concern mounts for the future of health care in Canada, CTV News Trend Line host Michael Stittle and pollster Nik Nanos sit down for an interview with health journalist and CTV News contributor Avis Favaro to get to the root of the crisis.

During the conversation, Favaro – Canada's longest-serving on-air medical correspondent – inventories the list of long-standing issues plaguing the universal health-care system Canadians rely on, from inconsistent delivery and funding cuts, to surgical delays, hallways lined with beds and under-staffed long-term care centres.

They get to the root causes of these issues and how the COVID-19 pandemic pushed an already weakened system to its limits.

Here is the episode and a full transcript of the interview. The text has been edited for clarity.

Michael: This winter in Nova Scotia, two women, Charlene Snow and Allison Holthoff, died after lengthy emergency room waits. In this episode of Trend Line, Nik and I want to do a deep dive on one issue, health care. And to do that, we're joined by health reporter and CTV News contributor Avis Favaro. Welcome, Avis.

Avis: Good morning.

Michael: Avis, I know you've you've got some stories to tell. Having reported on on the strain that our health-care system is under.

Avis: I want to just position it that I'm a huge fan of Canadian health care. I actually remember when my parents, who emigrated here from Italy, got a card that said OHIP, the Ontario health plan, and they were so happy and so excited. So it was1969. I realized they had been paying every time they had a baby. And this was completely liberating. So I'm a big fan, but this is a very hard time. And you mentioned two stories. Those are just two. There are many stories of people waiting for care in hallways. You're seeing bits of it all over the media. And I think it's really not a good time. You've got COVID that has added to the strain.

But any health-care worker will tell you this has been going on for a long time and governments have not really created robust systems. We'll get into that. But I've heard from people waiting six months for an MRI, six weeks for a blood test. I've heard from people who are still waiting for cancer surgery in various parts of the country and people who have actually given up and flown to the United States for an MRI. I mean, we're experiencing, I believe, six million Canadians who don't have a GP. One gentleman who wrote to me said that if you want care in his B.C. community, you line up at a walk-in clinic at 7 a.m. and pray you get into the lineup by nine because all the spots are filled. This goes against everything we thought about health care and preventive health care in Canada. Six million people without a doctor or a nurse practitioner. It's crazy. That's why people are so up in arms, so this is such an issue for them.

Michael: Thosee are some staggering numbers. And Nik, there's so much frustration out there and you've been tracking these issues of concern. Where does health care stand right now?

Nik: Well, it's a top issue, and to Avis's point, this is like a white knuckle issue for Canadians because most Canadians rely on a public health-care system. If you're in a car accident, you can get into the emergency pretty fast. From a polling perspective, when we look at the trend line and the proportion of Canadians that identify health care as our top unprompted national issued concern, well, check out the trend line at least back to 2005, up to present.

And you know, you can see that right now we're at a high, even higher now than it was during the pandemic, where Canadians identify health care as their top unprompted national issue of concern. So this is on the radar, but do you remember Bill Murray's Groundhog Day, where you wake up and he smashes the alarm clock? Well, health care's kind of like that. It's like every day we wake up and it's like we're repeating and having the same issues, the same stresses that we had before.

But now to Avis's point, in this post-pandemic world, it seems to be coming more intense, the pressure on the system and I think many Canadians are outright questioning how resilient is our health-care system in meeting our demands? And I think when they're asked that question, they're like, 'I'm not really sure how ready, prepared or resilient it is.'

22-HOUR AVERAGE WAIT TIME IN ERs

Avis: Absolutely. Just to follow up, I sense a lot of anxiety. The sense is that the health-care system won't be there when they need it. So where do you go if you don't have a doctor? You go to emergency. When you go to emergency, what's the average wait time? Twenty-two hours, when you look across the board, 22 hours. Canadians know that there's a trade off when it comes to health care. Everybody gets it, but everybody kind of waits and they understand that.

But 22 hours with rural emergencies closing where they have no doctors and walk-in clinics, it's just too much. And so you have people who have been in lockdown and everything who are now anxious about health care. And that's, I think, Nik, what's being reflected in your poll. People are worried: 'Maybe it's not there for me when I need it.'

Nik: At the same time, they don't know what the solution is, right? They know it's complicated. They know it's not necessarily throwing money at it, which creates another level. It's not like a lot of other public policy issues. And why don't we just use the pandemic as an example from an economic perspective? It's like, okay, so people might not be able to go to work. Businesses might be in stress. Let's spend stimulus and sent checks to people. That's a lot easier than the health-care system, which is much more complex, and Canadians are waiting to hear solutions, but I think we're not hearing a lot, at least from a lot of our political leaders.

Michael: You've both touched on this. At the center of it is a political dispute, let's say, from the federal government and the provinces. There's a huge fight on right now. They can't come up with a deal. One side's blaming the other. And I don't see Canadians having a lot of faith because as as we all know, this has been a fight that's been going on for pretty much as long as we've had health care.

Avis: The provincial governments position it as a fight; it's not a fight. Canadians want universal health care. They want reasonable delivery. They want preventive health care, which is what we've been sold on. But what I've noticed over my years of doing it, and most of my focus has been on health developments in health science.

But as an outside observer, what's become very clear to me through my 30-plus years and the pandemic is that the provinces are all doing their own thing and things don't line up, and they're doing things for political expediency over the best interests of the public.

I was at dinner with a health-care worker at one of the hospitals, and she said, 'absolutely, every four years it changes the direction Oh, we're going to privatize this. Oh, we're going to privatize long term care and different things.' So I think the public is confused and angry, and that leads to the anxiety. We can go into this. But what do you think, Nik?

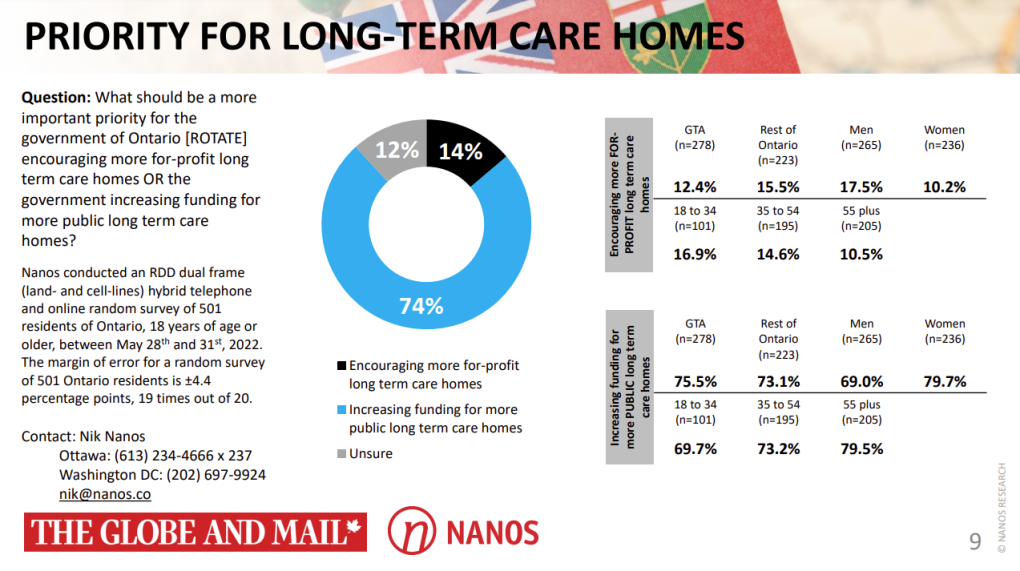

Nik: I would agree. And you talk about privatization and long-term care facilities in research that we did during the last provincial election in Ontario. And we asked Ontarians during the election, and this was for the Globe and Mail, how they'd like to fund long term care facilities or help on that front, 74% said increase public funding to long-term health-care facilities, while only 14% said that they would encourage a more private sector type stuff.

And what the survey shows is that people overwhelmingly just want to make sure that the public system is properly funded, that it can hire the people that we need. It would be like if this was a business, it would be like saying 'I don't have enough employees and I need to change my business model' when the reality is, you just need the employees to do the work and to deliver delivery of services to customers.

So, you know, I think that the first step in kind of dealing with this crisis is talking about how many beds do we need, how many nurses, how many frontline health-care workers are actually needed for the public health-care system to deliver what it needs to deliver? And we've never talked about that. It's like they start going to other options as opposed to focusing on the people in the system.

HEALTH-CARE WORKERS ARE 'EXHAUSTED' AND WE'RE LOSING THEM

Michael: On that note, Nik, we've heard a lot of surveys about burnout amongst health-care workers, where we all know we need more health-care workers. But through the pandemic, they've been through the wringer. And what steps do provinces need to take to counter burnout and to and to increase their their staffing?

Nik: It's pretty clear and Avis is probably hearing this on the front line, that all health-care workers from top to bottom are under stress and some of them are just walking away. And the pandemic was basically a tipping point for a lot of individuals who are already under stress. We have to remember that the system before the pandemic was under stress. And then we had the pandemic put on top of that. And now we have extra, post-pandemic pressure now. So should it really be a surprise that we're having trouble attracting people into the health-care sector?

Michael: What are you hearing about this, Avis? Are you hearing about health-care workers that have had burnout and they're not coming back?

Avis: Well, they're they're exhausted. I have a young niece who became a nurse and she's working in a hospital and she's only been there a few years, but she's already talking about finding an exit ramp. That's like, hello? It takes a long time to train these health-care workers. And there's absolutely no discussion, Michael, about retention. You don't poach other provinces or other countries, health-care workers, because we're all in the same boat. You grow them, you keep them. Good companies retain good employees. And I don't see any of that. I don't see provinces even counting properly on human resource planning.

I had to see the federal government hire a chief nursing officer, Leigh Chapman, to kind of work on it on a national basis because the provinces are like, 'Oh, we're short doctors. Oh, we'll take them from here.' You don't poach health-care workers, you poach eggs.

Nik: Absolutely. And, you know, think of it this way. For average Canadians, they expect that generally you can get the same level of health care regardless of what province you live in or where you reside or where you happen to be. And this whole idea, Avis, to your point of poaching health-care workers from other places. This is where we actually do need a federal, a national retention strategy, right? Because, let's face it, it doesn't matter whether you're in British Columbia or whether you're in P.E.I. or Ontario, you need to have a strategy to encourage new people to go into the sector and to retain who you have. And this would be like a natural place for the federal government to intervene, right? Not necessarily on delivering the health care. They could, but, you know, national standards, national solutions that benefit everyone, that cut across all the jurisdictions.

It should be a no-brainer for the federal government to say, 'let's have a national retention strategy on H.R. and a national strategy for building the talent and the people that we need and the system to deliver the health care that people want.'

Michael: We're going to talk about solutions later. But I want to touch on one thing that you both mentioned, planning and short term planning versus long term planning. That the provinces and the federal government perhaps haven't been the greatest at long term planning. And that seems to be becoming even more of an issue because of our aging baby boomer population. We talked about the importance of funding long term care homes, Nik. Avis, how do you see this playing out? I mean, we have this big population boom. Do you see any long term planning?

Avis: No, I don't. I mean, they can say they do, but honestly, I don't. What I have seen over my 30 years is this lurch, in that they'll do things just after they're elected that might not be popular. You're witnessing that in Ontario, where they're talking about privatizing and moving things topharmacies, which might be good or not, but they're only interested in their 3 to 4 years. And what will it take us to get elected? What looks good, you know, what will appeal to the right voters at the right time?

I don't see the structural planning. I mean, any Crown corporation, as Nik says, plans ahead. We know we have an aging population. We know we have a rural population, but they're not doing it. So I feel and I've seen it with privatizing long term care in Ontario. I've seen it also with, you know, trying to lever the number of doctors, 'hey, let's save money by having less doctors.' That's what happened. And then they cut it back. And what happens? We don't have enough physicians. Did they put in nurse practitioners? No, it costs more. You know, so there's I don't see it.

And the last thing is that during COVID, I realized that the provinces are all doing different things. So, for example, in seven provinces, they went, 'We're not going to deal with vaccine mandates. We need them on duty.' And yet you have B.C., Ontario, Nova Scotia, saying 'oh, no, we don't want previously unvaccinated nurses, even if they've had COVID -- health-care workers.' What, is the science different in B.C. than it is in Quebec? Is the science different in Alberta than Ontario? So the provinces can't even come up with a similar health-care plan based on science. So I've actually been listening to people who say it's time for the provinces not to run health care because they make it a political game.

'MASSIVE CRISIS' EMERGING WITH DEMOGRAPHIC BUBBLE

Michael: Nik, I was wondering if you could speak more to the demographics playing into this and the average age of Canadians now.

Nik: The intersection of demographics and the human resource crisis in our health sector is going to be a massive car crash, period. Full stop.

Here's a trend line of the median age of the population back from the 1970s to now. And you can see that we're just getting older. Now, if you notice in the last year, it's actually flattened a little bit. It's because of all the new Canadians that that have arrived in Canada. You know, if we bring in 400,000 to 500,000 new Canadians, that might flatten the curve a little bit. But the reality is, that we're going to be hitting, as soon as the baby boomers get a little older, we're going to hit a wall, and it's going to be a massive crisis where the demographic bubble hits what I'll say, the H.R. crisis that we're having in the health-care system. And it's going to be ugly.

And to Avis's point, I don't understand how anyone can't see the trend line on demographics and can't see what's happening in terms of H.R. retention. And put those two things together and say we have to deal with both of these issues, the fact that our population is aging, but also at the same time, that we need to make sure that we retain and have the health-care workers, the frontline health-care workers that are necessary. But I don't know what it is. It's like denial.

Avis: I think it just it doesn't serve their purposes because it's a short three to four year window. And if they fix the system in a good way and they lose the election, then the next government gets credit. And I noticed that when I put out a little note to ask people about what's going on, the immense amount of skepticism among Canadians that the current system will work, ever, is very high. They just don't believe there's really an incentive to long term planning. There's no visionaries to say, 'okay, let's chart the right course.' There's a lot of talk.

Nik: Avis, you remember what I remember. And you talk about the story of your parents and getting their OHIP card. There was a time when people were proud of the health-care system, proud of what Canada had done in terms of a public health-care system. And it was something that we talked about when we'd visit our friends and relatives in the United States and in other countries and stuff like that.

We're not there anymore, because, you know what? To your point, if anybody is talking about the health-care system, it's about going to the emergency room where your child might have a sprained arm or a broken leg and it's not life threatening and they're waiting, or they or they just have a non-threatening issue, but they don't have a doctor and they're in the emergency room for 20 hours.

POSSIBLE SOLUTIONS

Michael: Avis, I want to talk more about solutions for our health-care system. And one of the things you talked about is proposals to take some of the jurisdiction away from the provinces.

Avis: Well, I've been hearing people unhappy with the idea of how do we plan to fix this? And we understand that the prime minister and the provinces are going to be making some sort of a deal on February 7, where there will be more money given to the provinces to fix health care. But I think what people don't understand is that when money goes into provincial coffers and correct me if I'm wrong, the provinces don't have to say where it goes. And there's been a long history of the money going and not having a clear idea of the deliverables and the return of the income that they're getting in terms of patient well-being and care, timely care.

So I've been hearing people saying, 'okay, if provinces get more money, it's the definition of insanity, doing the same thing over again, expecting a different outcome,' and that we have to look at a bigger structural issue with many people and some doctors.

And then I discovered a petition that is saying make the deliverables, make the big planning, the human health resources planning, make the rural health-care picture, federal. Give the federal government more power to really make the changes that Canadians want for health care and put it on a steadier ship than provincially run health care, which is that 3 to 4 year lurch between elections and Liberals and NDP and that. And I'm hearing more of that. It's worth a debate.

Nik: I think I'd like to see an intervention. Here's what I'd like to see. I'd like to get the premiers and the prime minister in the room, and then I'd like to have patients come to them and tell them what they have to deal with so that they have to hear it first hand. And then I'd like front care health-care workers to go in and kind of tell them their story so that they can get it into their mind that they need to act, that this is more than just a political issue and that they need to start making long term decisions that are in the best interests of all the citizens of Canada.

Because I feel like we're hearing the same thing and the same type of posturing. We need to think outside of the box. Avis, to your point about about attaching strings. That's the way it used to be in the olden days. The federal government would fund universities and colleges and there'd be strings attached. They'd fund the health care. There'd be strings attached. As soon as that was removed, and I believe that was in the 1990s that that was removed. It changed everything because that accountability that you're talking about and that measurement and the deliverables was basically severed between at least the federal funding that went to provinces with certain intentions and what actually happened at the provinces where the provinces basically decided what to do with the funds that they received, based on what they thought was most important.

Avis: Do you know why those ties were severed? Was it political provincial demands?

Nik: I remember sitting with a cabinet minister one time, and I'd ask that cabinet minister, what was your most what's the one decision that you regret most as a cabinet minister? And that cabinet minister said,when we remove the strings that were attached to funding from the federal government and transfers, they said that was, in retrospect at the time, we thought it was good because it was part of the federation and us working together and allowing the provinces the fiscal flexibility to do what they needed. Right?

And that we weren't going to be as directive and let the provinces figure out what they needed. And I think that was also in the context of Quebec wanting more latitude and not wanting those strings attached. And I remember the cabinet minister saying that was the worst decision that I sat at a cabinet table that was made, because it was just wrong for Canada. We did it because we thought it would be good for the Federation in a kind of post-referendum world, but it was fundamentally bad.

Michael: To that point, though, Nik, how feasible is that once those strings are cut? Can you can you bring them back?

Nik: I think you can bring them back. It'll just cause a massive stink. All the provinces, the provincial premiers, will be up in arms because they'll say, 'How dare you tell us?' But you know what? The federal government has a responsibility. It collects taxes and it disperses taxes. It has a responsibility to account for the money that all the money that it spends and all the money that it transfers. That's that's my view.

Michael: Would you see that as a big political win for the Liberal government if they were to pull that off?

Nik: I don't know if they could. I don't know. Do you think they could? It would be a win. But could they do it? Would the province of Quebec ever agree to strings attached to funding from the federal government now that they've had that? I don't know.

Michael: If Prime Minister Justin Trudeau is looking for a major legacy before he potentially steps down...

Nik: Yeah, he'd have to quit politics right afterwards. I just think he's not going to be popular in Quebec.

Avis: Absolutely not. Because you see provinces moving towards like Ontario moving to privatize things because, you know, never waste a good crisis. We didn't hear it in Ontario during the election that they were going to do more private clinics and move that direction. But, you know, they're doing what works for whatever the Conservative government here wants to accomplish.

I do want to say, just on the private health-care system, I think that most Canadians don't realize we already have a lot of private health care. Every GP across Canada is a private corporation. A lot of the hospitals are private, not for profit corporations. Then there's the famed Shoudice clinic, which is grandfathered in and part of that is that they just do hernias, and high volume places have the best outcomes. So when you hear private care, it's a bit of a trigger word. And I just want people to sort of go, well, what kind of private private care?

Nik: Avis, to your point, I think most patients would be surprised that their physician pays for their office, pays for the staff, pays for the nurse, pays for all the equipment and stuff like that, which is why they're a small business. And it's a bit unfair when they talk about these buildings.

You know, they report on the buildings of some positions and they don't report, well, yes, that's what they're billing. But the reality is, how many staff are they paying for it? People confuse the billing with the salary or how much a physician might be making when the reality is they're paying for rent, they're paying for the receptionist, they're paying for all of the equipment, all of the overhead, all of the staff that they might need. There are a lot of things that are misunderstood in our system, there is some private role in certain specific things already.

Michael: I'm curious, Avis, what frontline health-care workers think about what Ontario Premier Doug Ford is doing, with using private clinics to ease up some of the backlog in surgeries.

Avis: Well, it's a mixed response. The ones that understand the role of private in the context of how private health care is done at the moment, understand that in order to clear things up, you might need a bit of that. It's just the way in Ontario it's done, so, for example, a lot of the cataract surgery has gone to one particular company that has turned out to be a donor to the Conservative government. So I think there's skepticism. The other thing, too, though, again, is how it looks or who it benefits. People are skeptical about that. Instead of listening to the frontline workers who are saying, 'hey, maybe it's better if we improve workflow.'

I remember a crisis in the 1980s when I was reporting on people who couldn't get heart surgery and they were dying waiting for bypass surgery and the health system in Ontario, and I believe other places, started to fix it by having specialized centers (where) patients would get to the next available hospital surgeon who could perform it. And it worked out, the triage system.

So, you know, if you listen to your frontline workers, they have good solutions. They're there, they understand how it works and how to make it better. Instead, the government comes down with these top-down decisions and, you know, less so in other provinces. But it raises a lot of questions. And I think they're in a way, nurses are in conflict with the Ontario government. They're capping their pay. They're not working on retention. Physicians are tired and leaving. I don't think that they have generally the support of the health system, the health-care workers, I should say.

Michael: Avis, I was curious if you've heard of any other ideas from doctors and nurses about long term solutions for this.

Avis: Well, a shout out to the frontline workers who have been working like crazy and are still doing the work. I was talking to nurses when my mom was in hospital with COVID and she passed in September. But I watched these nurses work so hard, and they were saying there were simpler solutions. Number one, retention. Number two, you don't make people work crazy shifts because you don't have staff. You have enough staff to back up what was needed. Right? They were exhausted. I mean, I felt so sorry for them. And if we weren't there 24/7 with my mom, nobody would be with her. It just that's just the way it is.

I've had some doctors talk about just, forget the provinces and look at a federal leadership. But also I've had people say, we came up with solutions in 2002 with the Romanow report, 47 recommendations. A lot of them were never taken into practice. And a lot of them, I read them the other day, and I thought, well, why don't we do some of these? Like electronic medical records so that someone can get care in different areas without a lot of paperwork? Why do we have duplication between provinces and a lot of managerial staff as opposed to it going more to health care?

That report has a lot of really great ideas that if they hadn't been implemented, might make our health-care system right now have been much more robust and look much better than it is and have much happier staff working across the board. But, you can post suggestions. But if there's no political will and if the electorate is kind of like, help us, what do you do?

Nik: And I think, Avis, to your point, part of the problem is mixed accountability. The feds play a significant role in funding health care and the provinces are delivering. And that mixed accountability has led to mixed results. Period. Full stop. And it's just it just messes things up because there needs to be someone accountable. And I think right now, just from a governance perspective, there's not one level of government that's fully accountable for health care.

And for average Canadians, they they don't really care what the governance is behind the curtain. As long as they get the health care, as long as they have access to public health care, and they get it in a reasonably timely fashion. Because to your point, they know that it's a public health-care system. They know there's you got to wait a little bit, but it's not going to be on demand. But the thing is that lack of accountability I think someone needs to take leadership on this, and I'm not sure whether provinces or the federal government are hot to take leadership on this. Maybe because it's a tough issue and not necessarily a political winner. This would be a great issue for someone that's going to retire. I'd just like to say that. A kind of like a legacy issue to say, 'okay, I'm not going to be the leader of whatever, but for the next two years I'm going to do this' and to just push it through, push through some leadership and accountability.

Because I think the problem is, is that for anyone that's seeking reelection, it's kind of like Vietnam, right? Get mired in jungle warfare and you're just in a swamp and there's no political win. And if there is no political win, you will never be around as a politician to do the victory lap. You'll be around as individual, retired politician, to take credit. But there'll be no short term gain.

Avis: Question for you, Nik, what level of government do you think should be accountable?

Nik: Well, I can just speak to the numbers. Canadians expect national standards. And they expect provinces to be able to deliver, or regardless of where you live, to get a reasonably comparable level of health-care service. So I would say that if you asked average Canadians what they'd want to see is the federal government lead on standards and implementation, but that there would be local operationalization of whatever the national plan was. Why don't we use an example? If you're in a rural hospital, you'd have to meet the national standard, but you still have some flexibility to deal with your special patients and the fact that you're dealing in a rural hospital as opposed to a hospital in a high density urban area.

But I think for average Canadians, if you'd ask them who should lead, they'd say public health care is a national priority. We need national standards. The federal government has to pony up and set those standards. But, you know, we should be allowing local health-care facilities some flexibility to meet the needs of their unique communities. I think that's probably the way they would go, but that it would mean a heavier hand for the federal government on this. What do you think?

Avis: I agree. I think people don't want the fighting. I think people I hear say 'stop the political games, stop politicizing health care,' which is what we saw happen to a large degree during COVID. The pandemic taught us that we need some sort of more national cohesiveness in it. And I agree with you, people want national standards. And there's no reason why someone in Northern Ontario should have their emergency closed because there aren't enough doctors, they're all in Toronto or other places.

So I think we're at that point, but I think people don't know how to ask for it or get it, because when they vote, they're voting on X and then the government in power can change it to Y, because there is no leadership. So how do you know when a public person, the only tool that we have is to vote, and the votes don't seem to matter? How do you enact this?

Edited by CTVNews.ca and Trend Line producer Phil Hahn

IN DEPTH

Budget 2024 prioritizes housing while taxing highest earners, deficit projected at $39.8B

In an effort to level the playing field for young people, in the 2024 federal budget, the government is targeting Canada's highest earners with new taxes in order to help offset billions in new spending to enhance the country's housing supply and social supports.

'One of the greatest': Former prime minister Brian Mulroney commemorated at state funeral

Prominent Canadians, political leaders, and family members remembered former prime minister and Progressive Conservative titan Brian Mulroney as an ambitious and compassionate nation-builder at his state funeral on Saturday.

'Democracy requires constant vigilance' Trudeau testifies at inquiry into foreign election interference in Canada

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau testified Wednesday before the national public inquiry into foreign interference in Canada's electoral processes, following a day of testimony from top cabinet ministers about allegations of meddling in the 2019 and 2021 federal elections. Recap all the prime minister had to say.

As Poilievre sides with Smith on trans restrictions, former Conservative candidate says he's 'playing with fire'

Siding with Alberta Premier Danielle Smith on her proposed restrictions on transgender youth, Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre confirmed Wednesday that he is against trans and non-binary minors using puberty blockers.

Supports for passengers, farmers, artists: 7 bills from MPs and Senators to watch in 2024

When parliamentarians return to Ottawa in a few weeks to kick off the 2024 sitting, there are a few bills from MPs and senators that will be worth keeping an eye on, from a 'gutted' proposal to offer a carbon tax break to farmers, to an initiative aimed at improving Canada's DNA data bank.

Opinion

opinion Don Martin: Gusher of Liberal spending won't put out the fire in this dumpster

A Hail Mary rehash of the greatest hits from the Trudeau government’s three-week travelling pony-show, the 2024 federal budget takes aim at reversing the party’s popularity plunge in the under-40 set, writes political columnist Don Martin. But will it work before the next election?

opinion Don Martin: The doctor Trudeau dumped has a prescription for better health care

Political columnist Don Martin sat down with former federal health minister Jane Philpott, who's on a crusade to help fix Canada's broken health care system, and who declined to take any shots at the prime minister who dumped her from caucus.

opinion Don Martin: Trudeau's seeking shelter from the housing storm he helped create

While Justin Trudeau's recent housing announcements are generally drawing praise from experts, political columnist Don Martin argues there shouldn’t be any standing ovations for a prime minister who helped caused the problem in the first place.

opinion Don Martin: Poilievre has the field to himself as he races across the country to big crowds

It came to pass on Thursday evening that the confidentially predictable failure of the Official Opposition non-confidence motion went down with 204 Liberal, BQ and NDP nays to 116 Conservative yeas. But forcing Canada into a federal election campaign was never the point.

opinion Don Martin: How a beer break may have doomed the carbon tax hike

When the Liberal government chopped a planned beer excise tax hike to two per cent from 4.5 per cent and froze future increases until after the next election, says political columnist Don Martin, it almost guaranteed a similar carbon tax move in the offing.

CTVNews.ca Top Stories

Grandparents killed in wrong-way crash on Hwy. 401 identified

A 60-year-old man and a 55-year-old woman killed in a wrong-way crash on Highway 401 earlier this week have been identified by the Consulate General of India in Toronto.

‘We made them safer and more fun’: Here’s what’s new about e-scooters

Electric scooters (e-scooters) have been gaining popularity in the capital and this season comes with some changes and updates.

The kids from 'Mrs. Doubtfire' are all SUPER grown up now, and we're not OK

The adorable trio of child actors from the 1993 classic comedy 'Mrs. Doubtfire,' which starred the late and great Robin Williams, are all grown up and looking back on their seminal time together.

Premier Legault reiterates that McGill pro-Palestinian camp must be dismantled

Quebec Premier François Legault reiterated that the pro-Palestinian encampment at McGill University must be dismantled while police remain 'on the lookout for new developments.'

Canadian Auger-Aliassime reaches first Masters final in Madrid with another walkover

Montreal's Felix Auger-Aliassime has advanced to his first ATP Masters final, and he hasn't had to play all that much tennis to do it.

Drew Carey is never quitting 'The Price Is Right'

Drew Carey took over as host of 'The Price Is Right' and hopes he’s there for life. 'I'm not going anywhere,' he told 'Entertainment Tonight' of the job he took over from longtime host Bob Barker in 2007.

The UN warns Sudan's warring parties that Darfur risks starvation and death if aid isn't allowed in

The United Nations food agency warned Sudan's warring parties Friday that there is a serious risk of widespread starvation and death in Darfur and elsewhere in Sudan if they don't allow humanitarian aid into the vast western region.

Two killed after collision with truck on Hwy. 417 near Limoges, Ont.

Ontario Provincial Police say two people were killed after a car and a transport truck collided in the westbound lanes of Highway 417 near Limoges, Ont. on Tuesday afternoon.

Police officer hit by driver of fleeing vehicle in Toronto

York Regional Police say they are continuing to search for a suspect in an auto theft investigation who was captured on video running over a police officer in Toronto last month.

Local Spotlight

Twin Alberta Ballet dancers retire after 15 years with company

Alberta Ballet's double-bill production of 'Der Wolf' and 'The Rite of Spring' marks not only its final show of the season, but the last production for twin sisters Alexandra and Jennifer Gibson.

B.C. mayor stripped of budget, barred from committees over Indigenous residential schools book

A British Columbia mayor has been censured by city council – stripping him of his travel and lobbying budgets and removing him from city committees – for allegedly distributing a book that questions the history of Indigenous residential schools in Canada.

Three Quebec men from same family father hundreds of children

Three men in Quebec from the same family have fathered more than 600 children.

Here's how one of Sask.'s largest power plants was knocked out for 73 days, and what it took to fix it

A group of SaskPower workers recently received special recognition at the legislature – for their efforts in repairing one of Saskatchewan's largest power plants after it was knocked offline for months following a serious flood last summer.

Quebec police officer anonymously donates kidney, changes schoolteacher's life

A police officer on Montreal's South Shore anonymously donated a kidney that wound up drastically changing the life of a schoolteacher living on dialysis.

Canada's oldest hat store still going strong after 90 years

Since 1932, Montreal's Henri Henri has been filled to the brim with every possible kind of hat, from newsboy caps to feathered fedoras.

Road closed in Oak Bay, B.C., so elephant seal can cross

Police in Oak Bay, B.C., had to close a stretch of road Sunday to help an elephant seal named Emerson get safely back into the water.

B.C. breweries take home awards at World Beer Cup

Out of more than 9,000 entries from over 2,000 breweries in 50 countries, a handful of B.C. brews landed on the podium at the World Beer Cup this week.

Kitchener family says their 10-year-old needs life-saving drug that cost $600,000

Raneem, 10, lives with a neurological condition and liver disease and needs Cholbam, a medication, for a longer and healthier life.