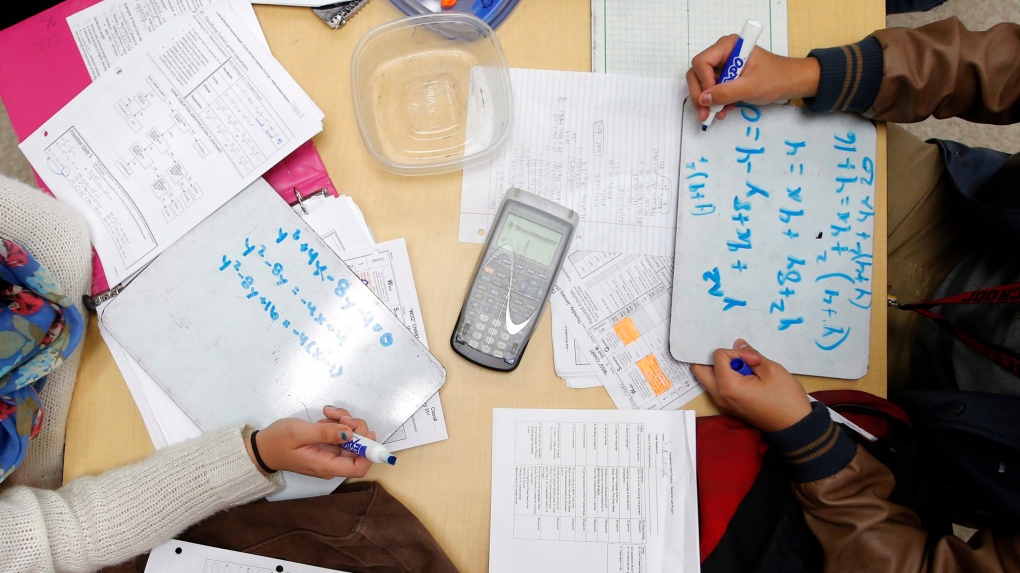

Most 15-year-old students in Canada met the basic standards for math and the country was among the top 10 performers in the tests, though scores have been dropping since 2003, according to a new global report.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development's (OECD) Programme for International Student Assessment's (PISA) latest study focused on mathematics and also tested the reading and science knowledge and skills of 23,073 students in 867 schools from all 10 provinces in Canada.

In the latest PISA study for 2022, it found that average scores in mathematics and reading were the lowest of any year going back to 2000, when Canada first participated in the assessments.

Though the country saw a decline in math, reading and science scores over time, the trend is similar in most other participating jurisdictions for the study, according to the Council of Ministers of Education, which represents Canada's ministers of education.

Canada was the only country in North America to make the study's top 10 for mathematic scores.

The 2022 report, released Tuesday, included students in 81 total jurisdictions worldwide. The PISA tests are intended to offer insights into how education systems are preparing students for the future.

Anna Stokke, mathematics professor at the University of Winnipeg, says she's concerned about the math performance of Canadian students based on the study's results.

"We're seeing more students performing at the lowest levels and fewer students performing at the top levels," she said in an email to CTVNews.ca.

To help improve math skills, she said they need to be the main focus in schools.

"Math is really cumulative and it's easy for kids to get behind if they don't get good instruction or if they don't get a lot of practice," Stokke explained.

The PISA report also found that 78 per cent of Canadian students achieved at least Level 2 – the baseline level of proficiency – in mathematics, beating the OECD average of 69 per cent. This means that they can understand simple mathematical scenarios, without direct instructions, such as converting prices into a different currency.

However, the proportion of students scoring below Level 2 proficiency rose by seven percentage points in mathematics, seven percentage points in reading and four percentage points in science compared to 2012 figures.

In Canada, about 12 per cent of students were top performers in mathematics, reaching Level 5 or 6, according to the report, compared with the OECD average of nine per cent. Six Asian countries and economies were the best performers, including Singapore (41 per cent), Taiwan (32 per cent), Macao (29 per cent), Hong Kong (27 per cent), Japan (23 per cent) and Korea (23 per cent). Students at these levels can model complex situations mathematically and evaluate problem-solving strategies, according to the OECD.

The PISA assessment found Canadian boys outperformed girls in math by 12 points, though girls did better in reading by 24 points.

Stokke of the University of Winnipeg noted that inquiry-based methods taught by many schools are more suited for advanced students.

"Students need systematic, explicit instruction, a rigorous math curriculum and a lot of practice," she said in an email to CTVNews.ca. "Teaching math through open-ended problems is what's gotten us to where we are today. Despite the warning signs that students have not been performing well when taught through open-ended problems, many school districts doubled down. You can't fix a problem by doubling down on methods that don't work."

In her view, another barrier is spending a lot of money on professional development for teachers that she says "is often grounded in inquiry-based methods that don't work."

"Parents and policy makers need to start paying attention to who is being paid to give professional development to teachers in Canada," Stokke explained. "That needs to change and we need to start focusing on giving students solid math instruction in schools."

Derek J. Allison, a professor emeritus of education at Western University in London, Ont., and a senior fellow at the Fraser Institute, said he believes Canada should recruit and train specialized math teachers.

"This is one of the most challenging subjects to teach and there are not enough specialist math teachers," he said in an email to CTVNews.ca.

In Canada and other jurisdictions covered in the PISA study, socio-economic status "was a predictor of performance" in mathematics.

As for barriers to math performance, the study found that in 2022, 44 per cent of students in Canada were in schools whose principal reported that instruction was hindered by a lack of teaching staff. Moreover, 24 per cent of students were in schools reported to have "inadequate or poorly qualified teaching staff."

"In most countries/economies, students attending schools whose principal reported shortages of teaching staff scored lower in mathematics than students in schools whose principal reported fewer or no shortages of teaching staff," the OECD stated.

Even with a more disadvantaged socio-economic profile than non-immigrant students, PISA concluded that immigrant students in Canada significantly scored better on average than non-immigrant ones by 12 points in math.

The learning environment posed a challenge for students, the study reports. About 21 per cent of students in Canada said they can't work well in most or all lessons compared to the OECD average of 23 per cent.

As well, 29 per cent of students don't listen to what their teacher says (OECD average is 30 per cent). Using digital devices was a distraction for 43 per cent of students (OECD average is 30 per cent) and 33 per cent get distracted by other students who are using digital devices (OECD average is 25 per cent).

Among all 10 provinces, Quebec scored the highest in math, followed by Alberta, British Columbia, Ontario, Prince Edward Island, Manitoba, Nova Scotia, Saskatchewan, New Brunswick, and Newfoundland and Labrador.

In Canada, students for the PISA study took two hour-long tests, which were a mix of multiple-choice questions and questions requiring a written response. The assessment is conducted every three years.