Two new studies released Monday suggest that the path to optimal health begins with a healthy paycheque.

The first study conducted by the Canadian Medical Association found that Canadians who have lower incomes report inferior health status compared to wealthier individuals.

The second study found that younger, poorer diabetes patients in Ontario run a higher risk of dying than their richer counterparts, though universal prescription drug coverage may help close the gap.

The second study was conducted by the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences and St. Michael’s Hospital.

CMA: ‘Wealth equals health’

The survey, conducted by the CMA, found that Canadians with lower incomes held a more negative view of their health than wealthier individuals, suggesting that good health starts with a healthy income.

The survey results also revealed that Canadians with lower incomes use health services more often than those with higher incomes.

“When it comes to the well-being of Canadians, the old saying that wealth equals health continues to ring true,” CMA President John Haggie said in a statement.

Only 39 per cent of survey respondents earning less than $30,000 a year described their health as excellent or very good, compared to 68 per cent of those earning $60,000 or more.

What’s more, in 2009, the CMA reported that there was no difference between lower- and higher-income Canadians when it came to how frequently either group accessed health services.

But that was not the case for the 2012 survey, which uncovered a significant gulf between lower-income earners and the affluent.

Almost 60 per cent of Canadians who earned less than $30,000 a year said they accessed health care services within the past month. Meanwhile, only 43 per cent of those earning $60,000 or more had accessed the same services.

“What is particularly worrisome for Canada’s doctors is that in a nation as prosperous as Canada, the gap between the ‘haves’ and ‘have nots’ appears to be widening,” said Haggie.

Education also appeared to contribute to the amount of time a person spent fretting about and sustaining their health. Individuals with a high-school diploma or less spent almost twice as much time and money on their health, compared to those with a university education.

Haggie told CTV News that one factor that may be causing the growing health gap between low-income and high-income Canadians is the economic downturn, which forces low-income families to make difficult decisions.

“You’re looking at an environment in which you have to make choices on a low income between heating in winter, eating and medication,” said Haggie.

“I have a patient for example, who skips their medication every second day to make it last longer,” he said. “It doesn’t do their health any good at all, and that means she has to access the system more often.”

The public opinion survey was conducted by research agency Ipsos Reid for the CMA, to appear in the organization’s 2012 National Report Card on Canadian health care.

The findings are a compilation of survey results from an online poll of 1,004 Canadians conducted between July 23 and 30, and a telephone poll conducted between July 25 and 30.

Drug coverage and diabetes care

Meanwhile, a second study found that younger, poorer Ontarians with diabetes have a 50 per cent higher risk of dying than their more wealthy counterparts.

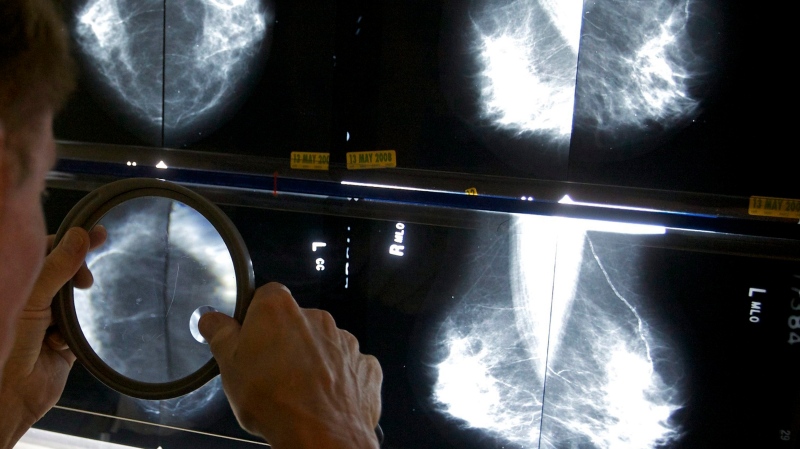

The ICES study found that while death rates among diabetes patients have fallen substantially, largely due to effective drug therapy, low-income patients under the age of 65 run a higher risk of dying compared to wealthier patients.

“In that group poor people are 50 per cent more likely to have a heart attack or stroke and poor people are also 50 per cent more likely to die than their high-income counterparts,” said Dr. Gillian Booth, the study’s lead author.

Booth told CTV News that these findings were consistent at all ages under 65, but the difference fell dramatically in the group over the age of 65 when universal prescription drug coverage kicked in.

The study noted that although diabetes drugs have become more effective over time, their cost has increased significantly over the past decade, making it harder for poor patients to afford treatment.

“We know that lower income groups are less likely to have private drug insurance,” said Booth.

Recent research also shows that low-income patients are more likely to withhold taking medications due to costs, said Booth.

“In the population that has universal health coverage there were far fewer deaths from diabetes,” said Booth.

The study used data from the health claims of more than 600,000 Ontario diabetes patients between April 2002 to March 2008.

The study found that socioeconomic status was a strong predictor of death and nonfatal heart attack or stroke among patients under the age of 65.

The study also looked at how diabetes patients were doing one year after experiencing a heart attack.

The findings revealed that income boosts long-term survival, with younger patients in the lowest income bracket having 33 per cent higher rates of death compared to their counterparts in the highest income bracket.

The study’s authors believe that extending universal prescription drug coverage to include those younger than 65 may help narrow the gap between the health status of rich and poor diabetes patients.

Currently, universal coverage for prescription drugs is only available to Ontario residents who are over the age of 65.

“Canada is one of the only wealthy nations that has a universal health care system that doesn’t cover prescription drugs for all of its citizens” said Booth.

“Based on our study and other evidence out there, I think we can be confident that making drugs accessible to all would help save lives.”

With a report from CTV’s medical correspondent Avis Favaro