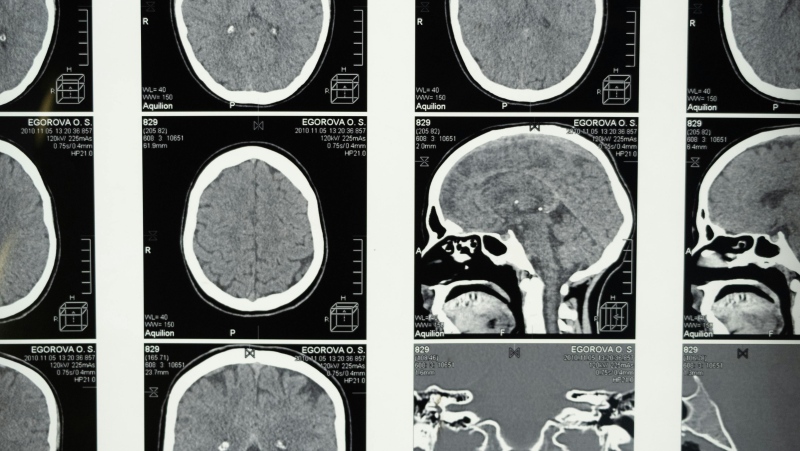

Scientists at the Moffitt Cancer Center in Florida have developed mathematical models that could predict how tumours grow and when to give medications to better treat cancer patients.

“Cancer is considered a complex system, not unlike the weather,” Dr. Alexander Anderson, chair of integrated mathematical oncology at the Moffitt Cancer Center, told CTV’s Your Morning on Friday.

Cancer is a disease in which mutations lead to uncontrolled and abnormal growth in cells. Part of what makes it so difficult to treat is that cancer is constantly evolving and adapting.

“Understanding the dynamics of a cancer, how it grows and evolves is not something that’s intuitive; it’s something that you can write down in equations and those equations can describe this non-linear and non-intuitive behaviour better than a human could,” said Dr. Anderson.

Most cancer treatments aim to cure cancer however, Anderson said that this might not always be the best course of treatment.

“When we give continuous, dose-dense therapies, what you’re treating is the sensitive cells and you’re treating so long that you wipe out all the sensitive cells and all that you leave behind are the resistant cells,” explained Anderson.

When there are only resistant cells left, treatment no longer works.

Instead, the goal of Anderson’s treatment isn’t to cure but rather to stave off metastasis and prolong life.

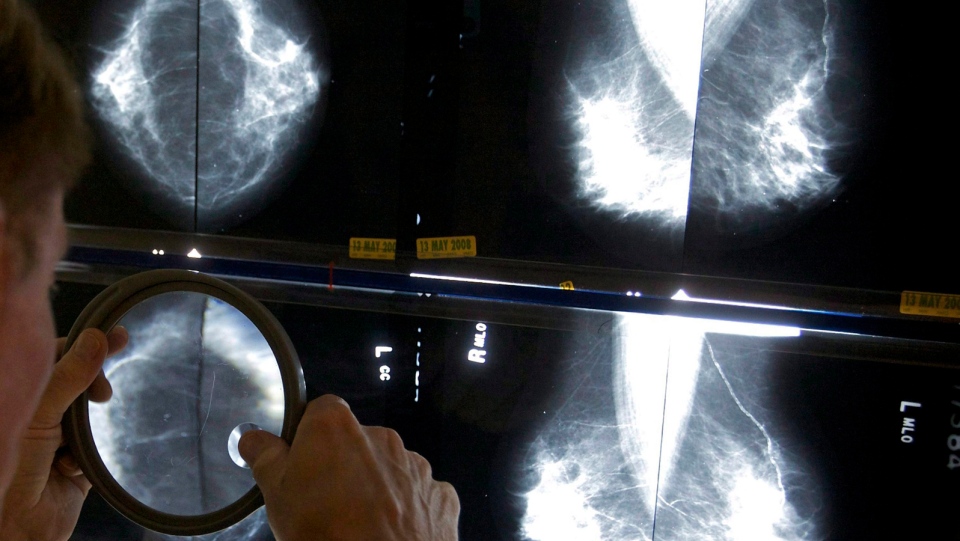

The mathematical models let doctors run various different treatment scenarios through an algorithm to determine the best one, without ever actually having to test anything on the patient themselves.

Using the algorithms, Anderson is able to find the sweet spot, not too much treatment and not too little, so that the treatment can be applied over and over again and ultimately control the tumour.

“It’s much more like treating cancer like a chronic disease,” he said.

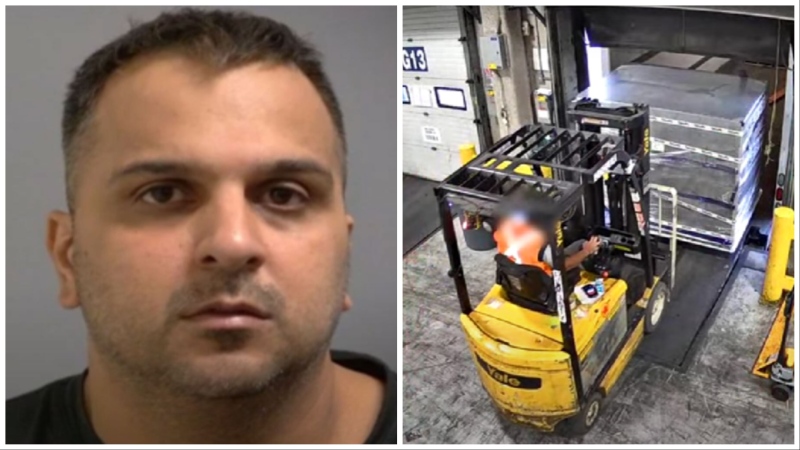

The Moffitt Cancer Center has been trialing this technique on metastatic prostate cancer patients for two years and according to Anderson there have been positive results.

“The median survival of those patients is 11 to 12 months with continuous therapies but we have patients now that are going out two and a half years,” he said. “We’re not curing them; we’re controlling their disease.”

Anderson is now working on more clinical trials that are looking at different kinds of cancer such as thyroid and skin cancer.

More research is needed before this approach makes its way into general practice but Anderson hopes that eventually it will be used in hospitals and cancer centres around the world.

“Tailoring mathematical models to each individual patient’s cancer and using that as a predictive tool shouldn’t be that far out. We’re talking five years probably,” he said.