A Canadian toddler is being celebrated in the scientific world as the first treated in utero for a genetic disease that would have quickly killed her.

"She's our little miracle baby, and she's showed us that (the treatment) does work," said Sobia Qureshi, mother of 16-month-old Ayla.

Ayla, who lives in Ottawa with her parents Zahid Bashir and Sobia, underwent an experimental treatment in 2021, while still a fetus, after prenatal tests showed she had Pompe disease.

It's an inherited and usually fatal disorder that ended the lives of two of her sisters. Ayla, however, is not only surviving, she is also thriving, according to her family and doctors, detailed in a New England Journal of Medicine study describing her case as the world's first in-utero treatment for the disease.

Doctors at the Ottawa Hospital and the Children's Hospital of Eastern Ontario teamed up to deliver an enzyme that is missing in those with Pompe. The therapy is sometimes used in babies after birth, or in adults with the disease. But in the landmark case, Ayla's mother was given six infusions between the 24th and 37th weeks of pregnancy. The enzyme was delivered into the fetal umbilical cord vein, using needles guided by ultrasound.

Babies born with infantile-onset Pompe disease usually have enlarged hearts and muscle weakness. The disease is rare, seen in fewer than one in 100,000 babies, though is more common in certain ethnic backgrounds. It's caused by a faulty gene that prevents cells from releasing certain waste products, which accumulate in the body.

"There's damage being done even before a baby's born and that damage can't be reversed," said Dr. Pranesh Chakraborty, a pediatrician and metabolic geneticist at CHEO and co-lead of the case study, who treated the family’s previously affected children. "No matter how well you treat after a baby's born, you may never actually be able to achieve an optimal outcome," he told CTV News.

Zahid and Sobia were initially unaware they were both carriers of the genes for this disease. They have also two unaffected children, ages 13 and 5.

When they decided to try for another child, they knew it was a genetic roll of the dice. When tests confirmed Sobia was carrying another fetus with Pompe, she was devastated.

"Shock, fear, upsetting obviously but then we took a breath and we were like, 'OK, how do we move forward now?'"

Dr. Chakraborty's research on their behalf led him to a team at the University of California San Francisco (UCSF Health) where Dr. Tippi Mackenzie and her team were preparing to launch a study in 10 children with diseases like Pompe, to see if giving them the therapy before birth would normalize their development.

Studies in mice had shown that early treatment worked, with the suggestion the replacement enzyme could better cross the blood-brain barrier, improving the development of the neurological system in utero.

When Dr. Chakraborty approached the Ottawa couple early in the pregnancy in 2021, they were excited but declined. The infusions would require Sobia to be in California for up to six months. She and Zahid were worried about travelling during the pandemic and leaving their other two children in Canada.

The scientists, however, worked out a deal. The Ottawa medical team could use the study protocol, with the UCSF researchers helping along the way and charting the effects.

After six prenatal enzyme replacement treatments at the Ottawa hospital, Ayla was born at term June 22, 2021. Tests show her heart and muscle development are normal.

Ayla's first laugh as an infant was an important sign.

"That's something that our other two daughters could not do," said Zahid.

She's now a busy toddler, walking and climbing and getting into cabinets and cupboards, "which is fantastic," her parents say with a smile.

Ayla underwent an experimental treatment in 2021, while still a fetus, after prenatal tests showed she had Pompe disease.

Ayla underwent an experimental treatment in 2021, while still a fetus, after prenatal tests showed she had Pompe disease.

Doctors were also monitoring for risks to the mother and fetus, including the risk of premature delivery. But there were no problems noted in Ayla's treatment.

"So we learned from this family that it's possible to diagnose and treat a fetus with infantile Pompe before birth," said Dr. Mackenzie. "I feel like it represents a new chapter in fetal therapy, one in which we can potentially treat and potentially even cure fetuses with many genetic diseases."

"I think that could be a game changer for families to know that," said Brad Crittenden, the executive director for the Canadian Association of Pompe, from his home in Pentiction, B.C. The key is early testing.

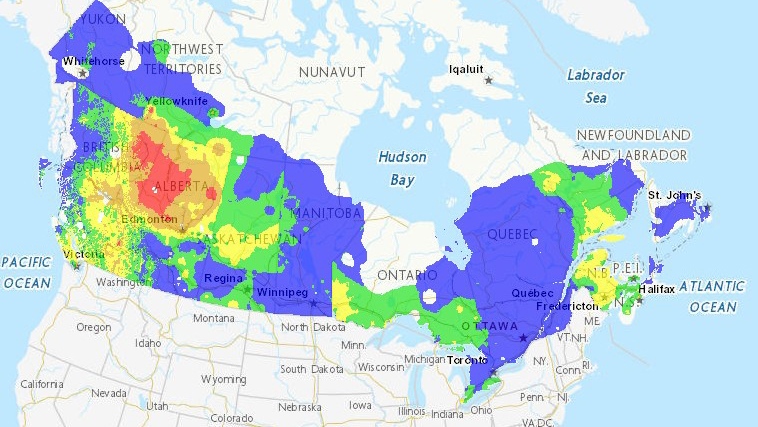

"Pompe is very underdiagnosed," he said, with some U.S states now starting regular screening in newborns. Pompe is not screened for in infants in Canada.

Ayla, meanwhile, continues to get weekly infusions of enzyme therapy at CHEO to maintain her development.

The U.S. researchers are now recruiting other families with pregnancies where the fetus has been identified as being affected with Pompe disease, or similar genetic disorders.

Canadian researchers want to treat other patients as part of a study but haven't been able to get funding to continue the work started with Ayla.

Her parents know she will be closely monitored for the coming years.

"We don't know what's going to happen in the future. All I hope for is that she has a happy, healthy and fulfilling life," said Sobia.