The diseases of humans and animals are strikingly similar, argues a new and fascinating book called "Zoobiquity: What Animals Can Teach Us about Health and the Science of Healing.”

Author Dr. Barbara Natterson-Horowitz, a cardiologist by training, says her perspective on medicine changed when she visited the Los Angeles Zoo for a sleepover with her daughter more than six years ago.

She struck up a conversation with some of the veterinarians, and became fascinated by how similar the ailments of animals are to those of humans. It wasn’t long before she was asked by the zoo to offer her medical expertise.

“I was lucky enough to be asked by the Los Angeles Zoo to perform some cardiac ultrasounds on some of their animals. And there, I listened to the veterinarians on rounds and I learned that their patients have many of the same problems that we do,” Natterson-Horowitz told CTV’s Canada AM Tuesday.

She learned, for example, that cocker spaniels, kangaroos and beluga whales can get breast cancer. Miniature ponies get diabetes. Siamese cats and Dobermans can suffer from obsessive-compulsive disorder and anxiety, but can be treated by being put on Prozac.

And she learned that animals can develop “capture myopathy” a stress-induced condition that’s a lot like “broken-heart syndrome” in humans.

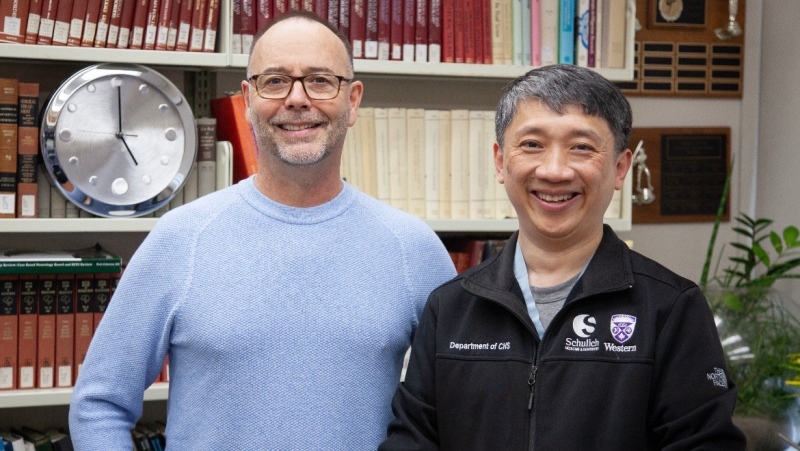

She decided to write a book about how to better bridge the knowledge of animal diseases and human diseases and enlisted the help of science writer Kathryn Bowers.

Bowers, too, was astounded by how similar even the strangest animals are to humans.

“This was what was fascinating to me as a journalist. I didn’t know that animals and humans could get so many of the same diseases. And it’s not just physical; it extends to behavioural,” Bowers says.

Natterson-Horowitz is still an attending cardiologist at the UCLA Medical Center and as a heart specialist, knows all the intricacies of the human heart. But she says it’s amazing to her how much more diverse the knowledge of veterinarians is.

“I think in a lot of ways, veterinarians have a lot harder jobs than we do. They have to be pediatricians, dieticians, geriatricians. They need to know mammals and reptiles and birds. And they have to do this with patients who can’t tell them what’s going on,” she says.

In fact, Natterson-Horowitz says, veterinarians have a joke about doctors: What do you call a veterinarian who treats only one species? The answer: A physician.

“Zoobiquity” argues that physicians could learn a lot from veterinarians. But Natterson-Horowitz laments that the culture of medicine doesn’t allow for much collaboration.

“I hope that changes,” she says.

"…So much of the knowledge that veterinarians and wildlife specialists have is applicable on the human side, but there are few bridges between the two.”

Natterson-Horowitz never expected that sleepover at a zoo would change the way she looks at medicine and at animals. But she’s glad it did.

“It’s really broadened my perspective as a doctor, as a mother and as a patient myself.”