Muscle stem cells can be made to produce a type of good fat in the body that helps burn energy, according to ground-breaking Canadian research that may one day lead to a treatment for obesity.

Researchers at the Ottawa Hospital Research Institute are the first to discover that adult muscle stem cells not only produce muscle fibres, but can also turn into what’s known as “brown” fat. Brown fat is a tissue that burns energy and is vital to the body’s ability to keep warm and regulate its temperature.

Having more brown fat is associated with being leaner, the researchers say, which makes a potential new method for inducing the body to produce more an exciting discovery in the field of obesity research.

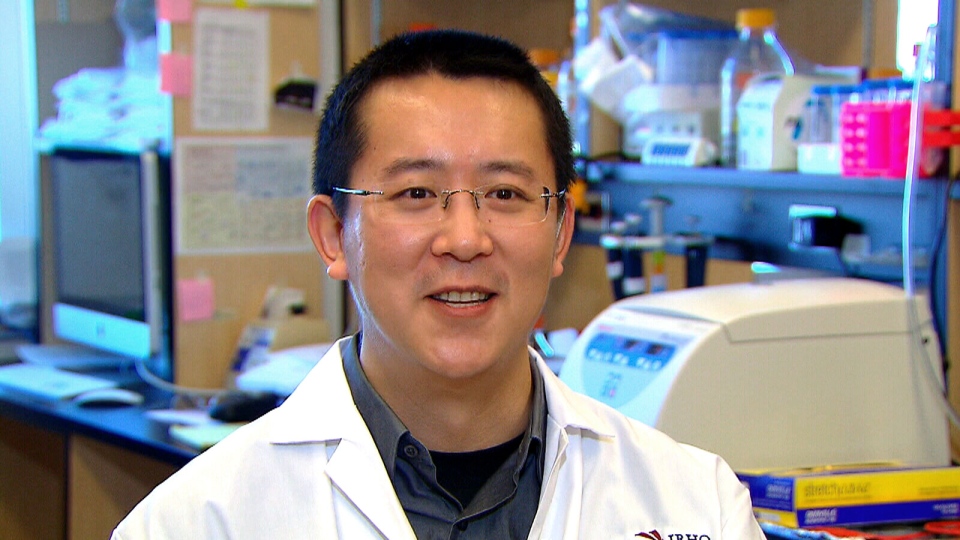

“It is the magic of stem cells,” study co-author Dr. Hang Yin told CTV News. “Stem cells have a lot of potential. In this case muscle stem cells, we can turn them into brown fat cells.”

Lead study author Dr. Michael Rudnicki and his team not only discovered that muscle stem cells can become brown fat, but also how. The researchers identified a gene regulator called microRNA-133, or miR-133, which helps stem cells turn into muscle. When there is less miR-133, those muscle stem cells turn into brown fat.

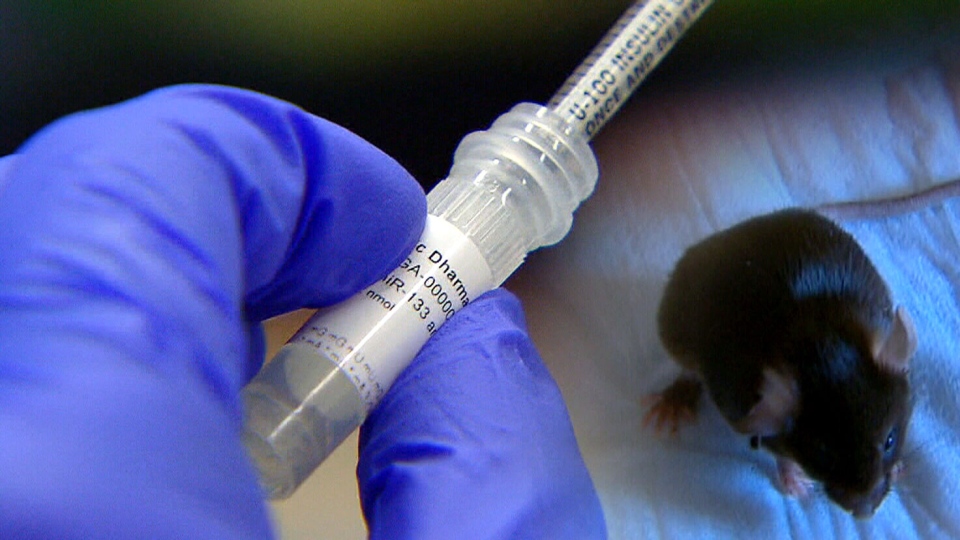

For their study, Rudnicki and his team injected adult mice with a substance that reduced their levels of miR-133 known as an antisense oligonucleotide (ASO). Those mice that received the injection had more brown fat, were leaner and were better able to process glucose. Also, a local injection into the hind leg boosted energy production throughout their bodies.

Rudnicki told CTV News that the mice who had the hind-leg injection stayed lean for four months afterward, “a shocking discovery” given that they remained on a high-fat diet.

Research into how to induce brown fat in humans and what that might mean for obesity is only in its infancy, the researchers say. However, their findings mark the beginning of a new path of study they hope will one day lead to the treatment or prevention of obesity.

"This discovery significantly advances our ability to harness this good fat in the battle against bad fat and all the associated health risks that come with being overweight and obese," Rudnicki, a senior scientist and director for the Regenerative Medicine Program and Sprott Centre for Stem Cell Research at the Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, said in a statement.

The findings are published in the journal Cell Metabolism.

A treatment for obesity could have a significant impact on public health worldwide, as an estimated 2.8 million people die each year from the effects of being obese or overweight, according to the World Health Organization. Obesity is associated with an increased risk for type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease and cancer.

As many as 25 per cent of Canadians adults are obese, the Public Health Agency of Canada says.

Human clinical trials are already underway to determine whether using an ASO to reduce levels of other microRNAs will help treat disease, the researchers say. But they acknowledge that a human treatment for obesity using miR-133 is still years away.

"While we are very excited by this breakthrough, we acknowledge that it's a first step," Rudnicki said. "There are still many questions to be answered, such as: Will it help adults who are already obese to lose weight? How should it be administered? How long do the effects last? Are there adverse effects we have not observed yet?"

Rudnicki told CTV that if human trials reach the same conclusions, scientists could one day develop drugs that impact miR-133’s relationship to brown fat. He said a pill with “a long-lasting effect” would allow obesity treatment to move away from the surgeries that are popular today.

The research has intrigued diabetes experts.

“This is fundamental science and is a long way from having clinical application,” Dr. David C.W. Lau, editor of the Canadian Journal of Diabetes and the president of Obesity Canada, told CTV in an email statement. “However, the science is quite exciting and novel, telling us that we could potentially turn on brown fat to burn energy instead.”

Mary Ellen Harper of the University of Ottawa, a specialist in brown fat, says it only takes about two tablespoons of it, or 50 grams, to keep blood-sugar levels steady.

She noted that while human trials are a long way off, she was “most excited” by the fact the mice that had the single injection were able to stay so lean and show better blood sugar control.

“I think it provides exciting potential for therapy for type two diabetes and obesity,” she told CTV.

The researchers say that they have already begun their next phase of animal trials.

With a report from CTV’s medical specialist Avis Favaro and producer Elizabeth St. Philip