At least five people have become ill after eating beef from the XL Foods plant in Brooks, Alta., which has ceased production amid a massive recall of the beef processed there. Another 18 cases are still being investigated to see if they are linked as well.

While the conditions of the five confirmed cases have not been released, one woman who survived an infection of E. coli O157:H7 has a harrowing first-hand account of the illness.

Melanie Dwyer-Joyce was just eight years-old when she became infected with E. coli while on vacation in Niagara Falls in 2001.

What exactly made her sick has never been precisely determined, but she suspects it was the spaghetti and meatballs she ate at a restaurant. She was the only one in her group who got sick that weekend and that is the only thing she remembers that no one else ate.

Dwyer-Joyce says it took about three days for the illness to kick in but when it did, it led to severe vomiting and diarrhea.

“My parents took me to the doctor and that doctor said it was probably just a stomach flu,” she told CTV’s Canada AM Thursday.

“But the next day it was even worse. My dad called one of the on-call doctors at a hospital and they were like, ‘Get her to the hospital right away.’”

Dwyer-Joyce spent the next two weeks in hospital as her kidneys became overloaded and started to shut down. She had developed hemolytic uremic syndrome, a potentially fatal complication of E. coli poisoning that affects about 10 to 15 per cent of all those infected.

E. coli O157:H7 bacteria release powerful toxins and it was those toxins that were killing off Dwyer-Joyce’s red blood cells, which were then clogging the filtering system in her kidneys.

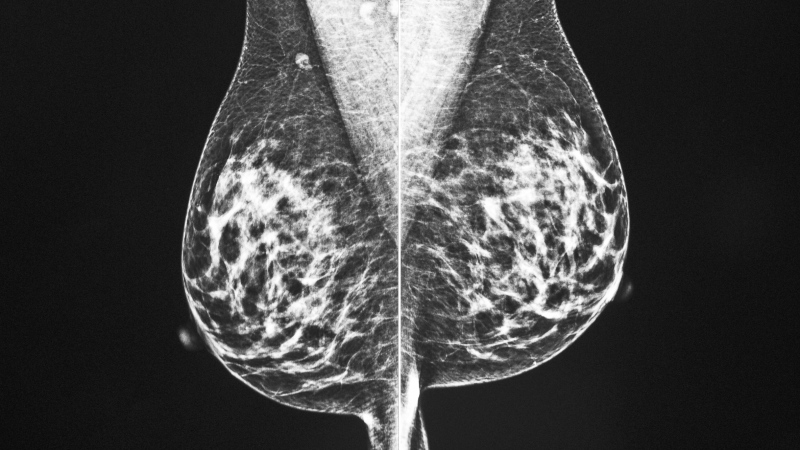

To help save her kidneys, doctors at Sick Kids Hospital in Toronto performed surgery on Dwyer-Joyce to insert a shunt in her stomach that was then hooked up to a dialysis machine.

The dialysis process was painful and every time the machine was switched on, Dwyer-Joyce would cry in anticipation.

“That was extremely painful and that would happen every half hour,” she remembers.

At the same time, nurses then had to take blood samples from her every four hours to ensure the dialysis was working.

The process did work, and after two weeks, she was able to go home. While Dwyer-Joyce was lucky, many infected with E. coli are not. Even those who survive can develop permanent kidney failure that will require lifelong treatment or a kidney transplant.

For the next five years, Dwyer-Joyce had to go for annual monitoring to see if her kidneys had sustained any permanent damage.

“A few years ago, I was given the all-clear and was allowed to stop going in for all the tests,” she says.

While people of all age groups are at risk for E .coli 0157:H7 gastroenteritis, the infection poses the largest risk to the very young and the very old.

According to the Kidney Foundation of Canada, at least 80 per cent of children who develop hemolytic uremic syndrome will require multiple blood transfusions, and around 50 per cent will need dialysis. Sadly, around three to five per cent die.