TORONTO -- The worldwide spread of a new coronavirus halted a decades-long air travel boom and is poised to forever change how we fly, how much we will pay, and perhaps how safe we will feel strapped into our seats among hundreds of others.

Few industries face more uncertainty about what the future holds after COVID-19 than passenger airlines. With success built on cramming as many people together as possible, airlines are now faced with that business model being turned on its head, at least for the foreseeable future.

The risk of the reality of being in close proximity to many people will likely abate – thanks to a vaccine, effective treatment, herd immunity, or perhaps a combination of all three – long before the fear does.

A germ-phobic public will be wary of closed-in and crowded spaces – literally the definition of an airplane. That’s not to mention the economic toll of lost jobs and battered revenues on discretionary household and business budgets. Only adding to the woes: a dramatic uptick in virtual meetings and remote work, and the success of the so-called flight-shaming movement that was already making some think twice about the carbon impact of flying.

- Complete coverage at CTVNews.ca/Coronavirus

- Coronavirus newsletter sign-up: Get The COVID-19 Brief sent to your inbox

Passenger confidence is key: 40 per cent of recent passengers said they expect to wait at least six months after the outbreak is contained to travel again, according to a survey by the International Air Transport Association released April 21.

Why will people fly in the short term? Certainly reunions with friends and family after a long period of isolation will be a strong draw. But there is no clarity around how long it might be before borders open to non-essential travel or when tourist attractions will be operational or large events, including festivals, sports matches, and concerts will return.

But long-term, our collective wanderlust and global supply chains, both fed by several decades of declining real costs for air travel, are powerful forces, too. In fact, TSA numbers have been slowly climbing for the last two weeks and in an earnings call Friday, United Airlines executives said searches for spring break travel for 2021 were higher than at the same time last year.

LESS LUGGAGE, MORE SCREENING

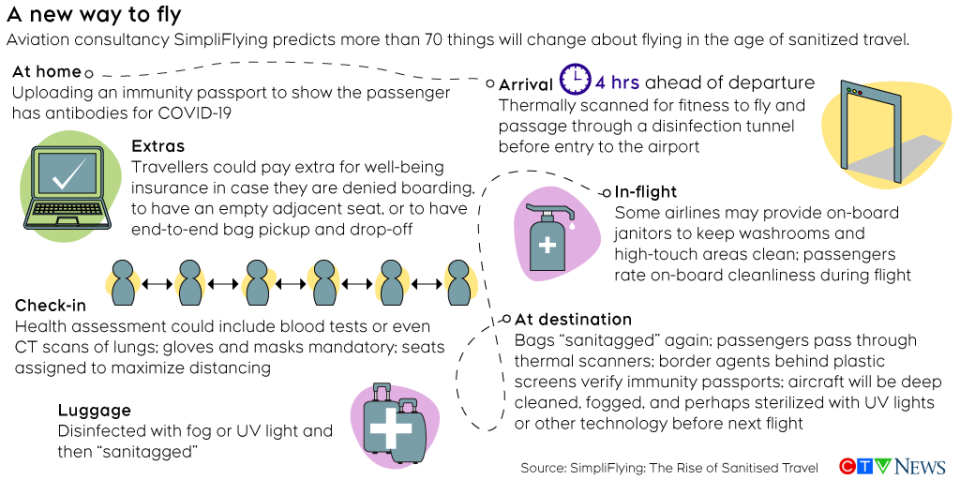

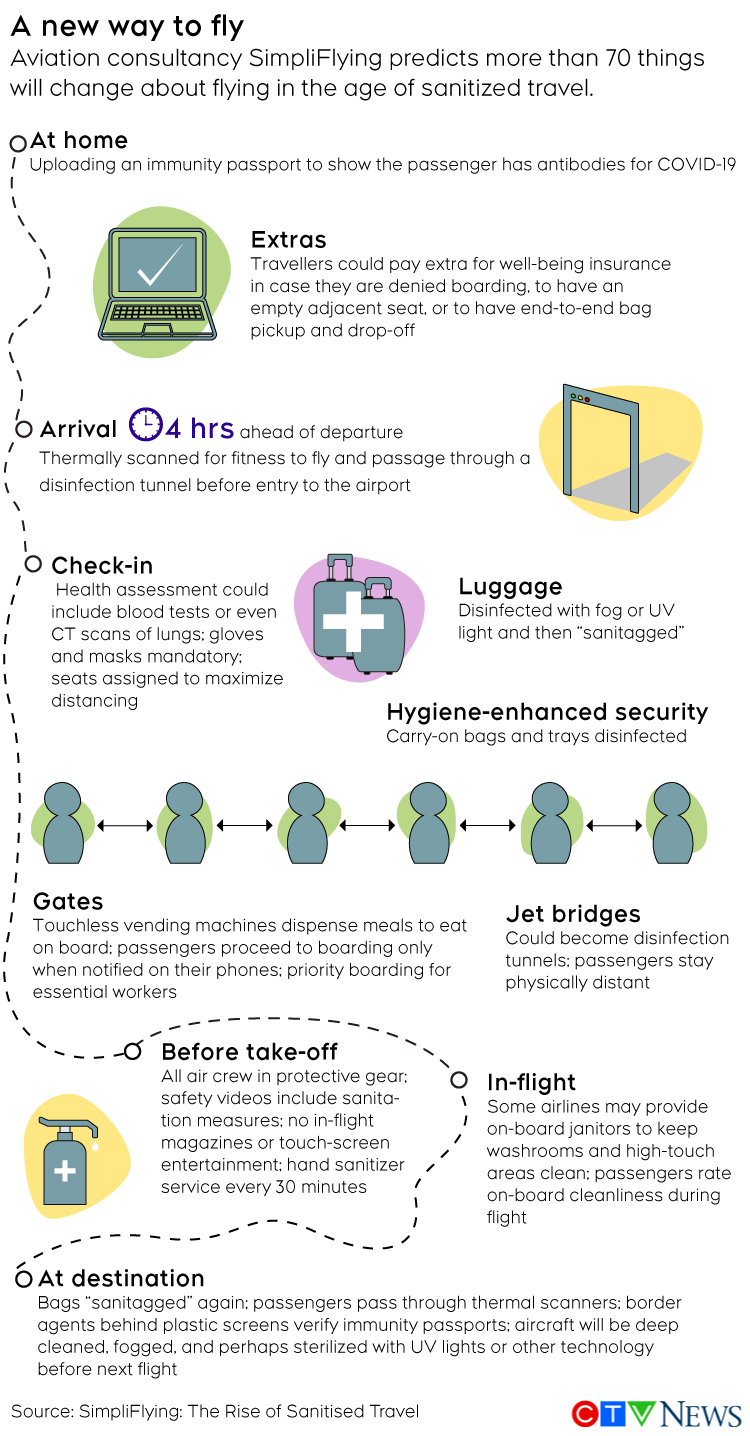

Airline experts say that much like the 9/11 terrorist attacks rocked air travel and transformed security measures in 2001, the COVID-19 pandemic is going to revolutionize health protection and cleanliness procedures in airports and airplanes.

“How you’re seated on board will be different. Processing at the airport is going to be different. But consensus on what that should look like requires research that is underway now,” John Gradek, a former executive at Air Canada, told CTVNews.ca in a phone interview from Montreal.

Gradek, who now teaches aviation leadership and airline management at McGill University, believes passengers will go through check-in, security and boarding without touching surfaces. That may involve voice-activated terminals, facial recognition or other biometrics.

Angela Gittens, director general of ACI World, which represents the world’s airports, told a live industry briefing on April 9 that health screenings are “likely to become the new normal” along with “solutions for truly autonomous, hands-free passenger self-processing throughout the journey.”

Screening for illnesses will likely include scanning for body temperature through infrared detectors, something that is common in airports in Europe and Asia, says Tae Hoon Oum, an air transportation specialist at the University of British Columbia, said in a phone interview from Vancouver.

That could be done en masse or be integrated into body scans, he says.

Air Canada announced Monday that it will be the first airline in the Americas to require pre-flight temperature checks for all passengers beginning May 15. Anyone deemed unfit to travel will be rebooked at no cost but will have to obtain medical clearance prior to travel, the airline said.

Decontamination chambers, such as one being tested at Hong Kong airport that kills viruses and bacteria on skin and clothes in 40 seconds, will likely become common, Gradek says. The airport is also using cleaning robots and testing an antimicrobial coating that destroys all germs for use on high-touch surfaces, such as handles, baggage trolleys and elevator buttons.

Gradek even foresees a time when passenger luggage is picked up at home and sterilized before it goes to the airport.

“I think we will be allowed very limited carry-on luggage. There won’t be rolling or overnight bags, just purses and briefcases.”

SPACED OUT AND WAITING LONGER

Another idea being floated is that of an immunity passport that would certify that the holder has been infected with coronavirus and has overcome it, presumably having developed antibodies to make them immune.

Dubai-based airline Emirates is requiring that passengers submit to a COVID-19 blood test. Could that become standard until a vaccine is found?

Gradek isn’t convinced, but says anything is on the table, including denying boarding to anyone who can’t prove they've been vaccinated once a vaccine becomes available.

Whatever form health screening takes, it won’t be unique to air travel, says Paulette Soloman, owner of The Travel Store, which provides travel bookings through storefronts and home-based agents in Prince Edward Island, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. They will become the norm at all departure points, including rail and water, she says.

She also anticipates airlines will scrap free on-board drinks and snacks and take a hard look at the design of seating and air circulation systems.

“There is no question there will be changes, but what really has to happen is that people feel safe and secure,” she said in a telephone interview with CTVNews.ca from her home near Charlottetown. She hopes that measures that are implemented are based on the best advice of public health officials and scientists.

“Right now, at the height of the crisis, we have to be careful about making big decisions that affect a lot of people.”

Transport Canada began requiring masks or face coverings for all passengers in airports and on-board planes beginning April 20.

Whether or not masks will be mandatory on flights in the long term remains to be seen, but travel consultant Barry Choi expects they will be a lot more common than they have been in North America until now. Many more passengers will also wipe down their tray tables and screens themselves.

“A video came out last year of Naomi Campbell wiping down everything around her seat and people thought she was crazy. Now you’ll be crazy not to,” says Choi.

Crowding around boarding gates or on loading bridges won’t be allowed to happen, says Gradek. Boarding will have to be sequenced into blocks of 10 or 12 people, which will lengthen the process.

Luggage carousels will have to be redesigned to space people out, too.

However the details become reality, says Gradek, it all adds up to passengers spending much more time at the airport than they do now.

FEWER PASSENGER, HIGHER FARES

As airlines return to something resembling more normal service, passengers are likely to see fewer flight options and will have to contend with more connections to get to where they’re going, an Air Canada executive said at an industry panel event last week.

And house-bound Canadians dreaming of future holidays will not see drastic seat sales, say experts who spoke to CTVNews.ca. Airlines can’t price their way out of this crisis.

Profit margins in the business are already thin.

According to data released in December by the International Air Transport Association (IATA), a trade group of nearly 300 airlines worldwide, net profit per passenger landed at $5.70, or 3.1 per cent in 2019, down from $6.22, or 3.4 per cent in 2018.

There are major regional differences though. Per passenger net profit was about $16 for North American airlines.

Gradek says physical distancing will require that flights be much less crowded – with 50 to 60 per cent fewer seats occupied. That could be a fatal blow to the business model of low-cost carriers, such as Swoop, Flair, Rouge and Ryanair. He says the disruption will be particularly felt in Europe.

And it will inevitably mean fares will rise. Fewer paying customers means each pays more to get the plane off the ground. And all the cleaning and disinfection that will be needed to convince people it’s safe to fly will come with a cost, both in labour and in time on the tarmac.

If new processes double or triple current cleaning times, that amounts to fewer flights per day, says Gradek.

“We’ve been conditioned to these lower fares, but the fact is that the real cost of flying has fallen significantly over the last two decades. The industry has created a monster because passengers now expect this lower level of pricing,” he said.

“The pandemic will entirely change the conditions. The cost of flying will increase because the real costs will go up.”

There are pluses to that, most notably more sustainability for “oversaturated” tourist sites, says Gradek, pointing to Machu Picchu in Peru and Venice as examples. Much of the world has witnessed the return of wildlife, clean air and clear water when humans stop moving around so much.

“We have an opportunity to better manage these sites if we don’t have a carte blanche ability to fly wherever we choose.”

REAR-FACING SEATS?

Air Canada announced Monday that it will automatically block adjacent seats from being booked until June 30, even among parties travelling together, unless a party includes a child under 14 or someone else needing assistance.

Blocking off seats will be an easy decision in the short-term, when demand is low anyway, says airline analyst Seth Kaplan. But will it continue when it means turning away business?

He says governments could regulate passenger loads to enforce physical distancing or consumers may choose to only fly with carriers with lower passenger counts. While he thinks that most people are “more permanently germophobic than we were before” he’s not sure consumers will continue to want to pay for less crowded planes once a vaccine is in place.

“It’s generally best to bet on people choosing what’s cheap,” he said in a call with CTVNews.ca from his home in Washington, D.C.

Cleanliness won’t drive decisions any more than safety has in the past, says Kaplan. It’s not that consumers don’t care about those things, it’s just they expect them and take them for granted.

Eventually, seat configurations could change, says Oum, who is president of the World Conference on Transport Research Society. An Italian airline design company released a concept drawing featuring middle seats facing backwards and plastic screens between passengers.

But that would be far from an overnight process and would require enormously expensive retrofits, he says.

A lot of ideas are being bandied around in the midst of this crisis, says Kaplan. But if they aren’t practical and don’t suit customer needs, they won’t stick long-term. He doesn’t think passengers will put up with having no carry-on luggage, for instance.

Fallout from the pandemic could also create clashes with other social priorities, says Kaplan.

For instance, if each flight has fewer people on board and there are more planes in the air, that will only intensify climate change concerns.

More people wearing masks in airports, and potentially less physically screening of luggage, could raise security implications.

But Choi sees a real opportunity, too. He says he will be hesitant about jumping on a long-haul flight for a while, so he’s going to explore his own country through road trips once they are deemed OK again.

“I think people will be considering trips they never would have considered before.”

In response to questions from CTVNews.ca, WestJet spokesperson Morgan Bell says it’s too early to tell what air travel will look like long-term.

“COVID-19 and its devastating impact on all aspects of life globally has not yet run its course. To suggest that air travel will look a certain way in the future would be speculation as the effects of this pandemic are unprecedented.”

WHAT ARE THE RISKS?

The conventional wisdom about the risk of transmission of infectious diseases in flight long centred on concern about two seats forward and behind, and on either side of the person shedding the virus, says epidemiologist Timothy Sly.

SARS called that into question when a so-called “super-spreader” travelling on an Air China flight from Hong Kong to Beijing on March 15, 2003 directly infected 20 passengers – some up to seven rows ahead – and two crew members during the three-hour flight. That 72-year-old man died a few days after the flight.

“The incident was clearly atypical, but it does suggest we should revise assumptions about infective ‘danger zones’ in passenger aircraft,” Sly, who was involved in the management of SARS in Toronto and who is now a professor at Ryerson University, said in an email to CTVNews.ca.

But the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in February repeated the two rows up, two rows back guidance for defining “contact” with an infected COVID-19 patient.

A team of researchers from Purdue University that examined SARS data last year found that passengers within seven rows of an infected person on a five-hour flight on a Boeing 767 would have a one-in-three chance of contracting the illness on a five-hour flight.

They concluded that having air flow upwards rather than downwards as is standard now cut the risk by at least half.

Sly says while COVID-19 remains active, airlines will have a difficult task in ensuring the well-being of passengers, but also of flight attendants, who move among all the passengers, often in close quarters, and on multiple flights in a week. A number of employee groups have expressed fears about their safety, demanding more protective gear as cases among flight crew mounted.

“The problems in confining a couple of hundred people in an aluminum cigar-tube at 38,000 ft for five, 10 (or) 18 hrs with at least 12 people within each person's two-metre radius seems to be a bit unhinged when compared with the restrictions over the last couple of months,” said Sly.

Widespread research is underway to tackle germ transmission on airplanes, including self-sanitizing toilets, ultraviolet lights, using robots and artificial intelligence to disinfect planes, and advanced air exchange systems. But none of that comes quickly or cheaply.

And different jurisdictions could have different rules. For instance, aviation regulators in China are now requiring that washrooms be sanitized in-flight every two hours or after they’ve been used by 10 passengers.

To its cabin cleaning measures, Air Canada is adding “state-of-the-art electrostatic sprayers to ensure a deeper clean with hospital grade disinfectant.”

For the few planes it still has flying, WestJet has added fogging to its cleaning regimen, which disinfects a plane’s interior with a hydrogen peroxide-based solution. The process takes approximately 15 minutes to complete, with the product dissipating within 20 minutes.

“Fogging enables us to thoroughly disinfect an aircraft at any time with little disruption to our guests and operations,” WestJet said in a March 5 blog on its website.

The company says it uses HEPA filters for air circulation, similar to what is used in hospital environments, to remove viruses and bacterial from the air. Fresh air is circulated into the cabin every two to three minutes.

“We hold ourselves to the highest standard to create an environment as clean as realistically possible and continue to expand and enhance our sanitization measures onboard to keep guests and crew safe.”

WHAT WILL RECOVERY LOOK LIKE?

For weeks on end, airports have been eerily empty, except for tarmacs, runways and taxiways where about three-quarters of the world’s commercial aircraft are lined up wing to wing and nose to tail.

Worldwide lockdowns grounded about 90 per cent of flights in North America. The Transportation Security Administration in the U.S. said fewer passengers arrived at American airports in April this year than on any one day in April 2019. The agency said it screened almost 2.3 million passengers on March 1. By April 8, that number was under 95,000, a daily number not seen since the 1950s. (Canada does not release passenger screening numbers.)

But we know that Canadian airports are handling a trickle of passengers compared to a flood. At the nation’s busiest air hub, Pearson International Airport in Toronto, about 200 flights carrying 5,000 passengers were taking off at the beginning of April, compared to 1,200 flights and 130,000 passengers each day before the pandemic.

Calgary airport is forecasting a 60 per cent drop in traffic in 2020 over 2019.

It’s so many adjectives: remarkable, unprecedented, uncharted and certainly devastating.

The global airline group IATA estimated in January the new coronavirus would be a US$29-billion hit to the industry. On March 5, that was revised to $113 billion.

On March 24, IATA revised its forecast to a loss of $252 billion and three weeks later, it offered its most recent projection: a loss of $314 billion. That’s 55 per cent of the revenues for 2019.

The organization estimates a 39.8 million reduction in passenger volumes in Canada for 2020 and has warned that half of the world’s airlines face bankruptcy in two to three months without government help.

Many jurisdictions have given direct aid to airlines, but some, including the U.S., have mandated that much of it must go to employees. Canada has not directly promised cash for its carriers, though they already benefit from general wage guarantee programs. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has said more aid for airlines is coming, but nothing has been announced.

The federal government, which owns the land on which 21 airports sit, has waived rent payments from March through December, amounting to $331 million in relief.

As to when airlines will see sunnier skies, recovery scenarios and timeframes vary by expert.

Oum thinks that without a second-wave of virus cases, that about half of air travel demand could return by the end of the year and that full recovery might take two years.

He believes a rebound will begin in the second quarter, with some uptick in international operations and stronger demand for domestic service. Lucrative business travel – averaging five to six times the fares of discount travellers – will be the slowest to return.

“They learned that digital conferencing services could accomplish about 70 per cent of the work without the travel.”

Tim Strauss, vice-president of cargo at Air Canada, is also optimistic about a recovery this year.

"I think by Christmas you will see a significant amount of flying again," he said at a livestream panel event hosted by Canadian Club Toronto last week. "I do think in the fourth quarter, we'll be flying to most places around the world and certainly domestically."

Airline analyst Helane Becker at investment bank Cowen predicted at the same event that the North American airline sector will be about 30 per cent smaller at the end of the year but that no major airline will go bankrupt.

Her firm forecasts it will take three to five years for North American air travel to be restored to pre-pandemic levels and that it will take five to seven years for international passenger numbers to rebound.

But in the meantime, Air Canada is “living through the darkest period ever in the history of commercial aviation," Calin Rovinescu said Monday in the airline's first-quarter report. It showed earnings sank almost 90 per cent and a net loss of $1.05 billion.

The freefall won’t last forever. One day the pandemic will be behind us and planes will be full again, says Gradek, but hard lessons will have been learned. In the end, flying is a unique casualty of COVID-19.

“The distribution of this virus from Wuhan to the rest of the world was facilitated by the airline industry. Out of this, there will be much better detection of a virus anywhere in the world and the industry will react much more quickly.”

When Soloman bought her travel company last November after years in the business, it was a great bet. Travel was booming locally, nationally and internationally, and forecasts saw a good year ahead for the industry.

She’s confident growth will eventually return. Initially, demand will come out of all the credits issued for trips that were postponed by the pandemic restrictions.

“I think after this period of isolation and being cooped up, there will be pent up demand to travel. I think many of us will really value our ability to travel after all of this but it’s going to take a while.”

New Normal is a CTVNews.ca series looking at how life will change in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Edited by Senior Producer Mary Nersessian, infographic by Mahima Singh

Correction:

This story has been updated to reflect that Canada's airlines only began to require that passengers wear masks after Transport Canada's directive that took effect April 20.