Paying living kidney donors $10,000 would likely increase the number of transplants being performed, and end up being less costly than the current organ donation system, a new Canadian study concludes.

The study, co-authored by researchers from the University of Calgary, found that paying $10,000 per kidney would likely result in an increase in the number of potential living donors.

If donation rates rose by even five per cent – a conservative estimate, in the authors' view -- the health care system would end up saving money, since the cost of years of dialysis would likely be even higher.

“We based that on a previous survey that we did where we found that over half of those who answered stated that for $10,000, they would be willing to consider donating a kidney to a family member or friend,” study co-author Lianne Barnieh told CTV News.

And if donation rates rose even more than that, the authors say the costs savings could rise too.

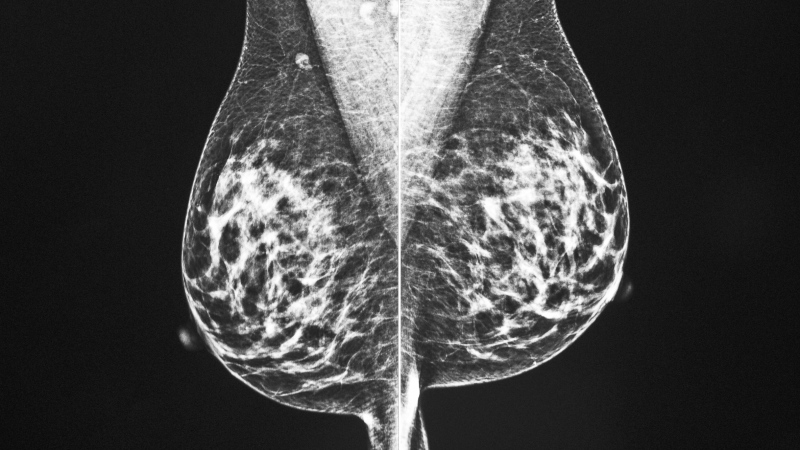

Many patients living with renal failure face a lifetime of dialysis to perform the waste removal work of their damaged kidneys. While dialysis can manage the condition, a transplant is the best treatment and extends life.

There is demand: More than 3,000 people in Canada are currently waiting for a kidney transplant, accounting for approximately 80 per cent of the all people in Canada waiting for an organ.

Kidneys can be transplanted from deceased donors, though organs from living donors are typically healthier and lasts 15 to 20 years longer, on average, compared to a deceased donor’s kidney.

But donation rates from both living and deceased kidney donors are low and have remained relatively unchanged over the last decade, the authors write in the Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology.

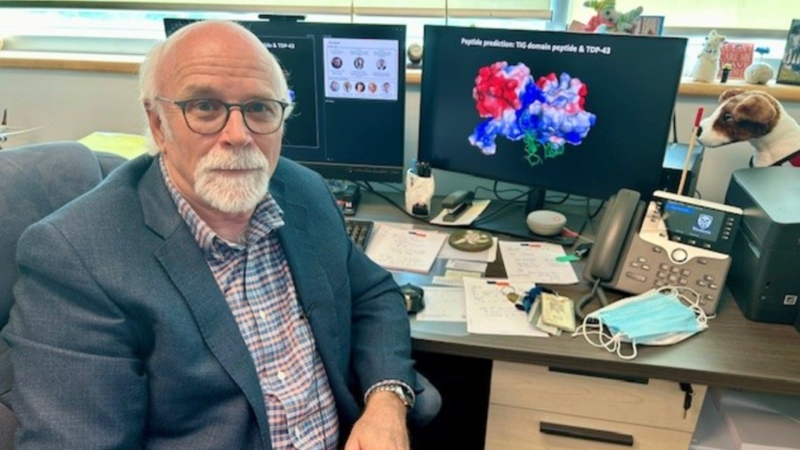

Barnieh, a University of Calgary researcher, and kidney specialist Dr. Braden Manns created a model to estimate the cost-effectiveness of paying living kidney donors compared to keeping patients on dialysis for years.

They looked at the cost data from a group of kidney patients over three years and determined that if living kidney donors were paid $10,000 apiece and donation rates rose five per cent, there would be a net savings of about $340 per patient compared with the cost of ongoing dialysis.

As well, the transplant would extend the time a patient would have a better quality of life, with scores of quality-adjusted life years, or QALY, rising by 0.11 years.

If donations rose by 10 per cent or 20 per cent, the cost savings would jump to $1,640 and $4,030 per patient, respectively. As well, quality-adjusted life years would rise by 0.21 and 0.39, respectively.

In 2012, Manns had a team survey 2,000 health professionals, kidney disease patients and members of the general public about offering payment to living and deceased kidney donors. A full 70 per cent of respondents said they supported offering payment to deceased kidney donors.

While 47 per cent of the general public supported offering payments to living donors, only 14 per cent of kidney patients and 27 per cent of health professionals liked the idea.

In an accompanying editorial to this week's study, the University of Pennsylvania's Matthew Allen, and Dr. Peter Reese, proposed beginning an actual study of the effect of financial incentives on donation rates and patient outcomes.

“Current trends regarding the use of financial incentives in medicine suggest that the time is ripe for new consideration of payments for living kidney donation… Reassurance about the ethical concerns, however, can come only through empirical evidence from actual experience,” they wrote.

Human organ commodification

Some say the research raises ethical and legal questions.

“The buying and selling of organs for transplantation is illegal everywhere, and it should remain illegal,” ethicist Arthur Schafer said in an interview with CTV News.

But laws have not stopped the selling of kidneys on the international black market, where one can sell for $200,000.

And some suggest that moving to a paid donation system would mean the most needy would be the most likely to sell kidneys.

“You’re probably going to likely attract the poorest segment of society,” said Dr. Jeff Zaltzman, a scientist at St. Michael’s Hospital in Toronto. “People of more substantial means would not do that for $10,000.”

With a report from CTV News’ Jill Macyshon