New research is showing that low-level oxygen deprivation may help people with spinal-cord injuries regain movement and strength.

The U.S. study, published earlier this week in the American Academy of Neurology medical journal, showed that exposing patients with limited movement to short periods of low oxygen helped them walk better and for longer periods.

Previous studies have shown that animals deprived of oxygen for short periods resulted in a flood of brain chemicals that help repair spinal cord cells.

Now, for the first time, researchers in Atlanta have tested the effects of low-oxygen therapy on people.

Over a five-day period, 19 patients with partial spinal cord injuries were given intermittent bursts of low oxygen, known as hypoxia. The patients breathed through a mask for about 40 minutes a day, receiving 90-second periods of low oxygen levels, followed by 60 seconds of normal oxygen levels.

The simple treatment alone helped patients walk faster, researchers found.

And patients showed “significant” improvement in their speed and endurance when the therapy was combined with rehabilitation exercises.

“What this tells us is that intermittent hypoxia may be a powerful way to dramatically enhance the benefits of current therapies that are already being used in spinal cord injury rehabilitation,” said study author Randy Trumbower, a researcher at Emory University’s School of Medicine, based in Atlanta.

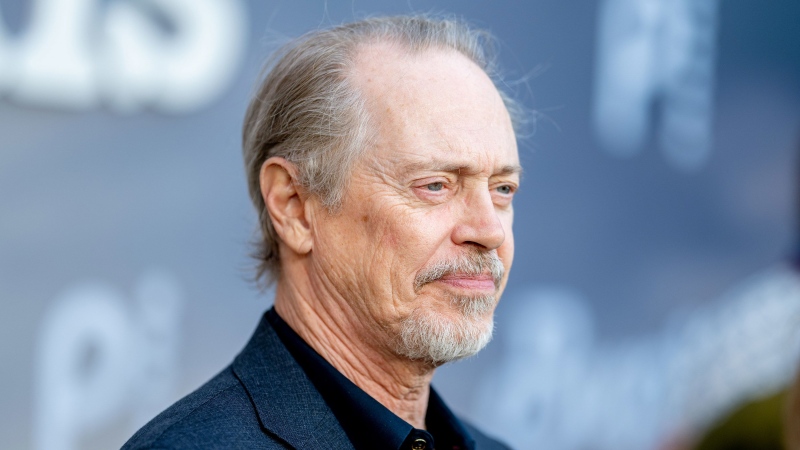

Christopher McClendon’s spine was damaged in a car accident – an injury that makes walking difficult for him.

But after participating in the unusual experiment, McClendon was able to move faster and easier.

“I felt a little bit more stable in my walk,” he told CTV News. “I felt like I had a little bit more control.”

The results are counterintuitive, given that low-oxygen environments are usually considered dangerous. Mountain climbers, for instance, know that being in such environments can lead to altitude sickness and other health problems.

“It was a bit edgy but when one actually looks at the science, it actually is supported by a pretty strong scientific rationale,” said Dr. Michael Fehlings, a surgeon with the University Health Network in Toronto.

The results are considered preliminary research, and doctors don't know yet if it works in patients with more severe forms or paralysis.

"It's not the big breakthrough, it's not going to influence standards of care at this point, and I think it does require further research," Fehlings said.

Trumbower said to the best of his knowledge, the clinical intervention is safe and his trial found no adverse effects. But he cautioned that individuals interested in trying it must do so in a clinical environment and under proper supervision.

Researchers say they are planning more trials, something McClendon welcomes.

“I really can’t wait until it develops into its potential,” he said. “I hope they call me.”

With a report by CTV’s Medical Specialist Avis Favaro and producer Elizabeth St. Philip