WASHINGTON -- Sarah Ball was a 15-year-old high school sophomore at Hernando High School in Brooksville, Fla., when a friend posted on Facebook: "I hate Sarah Ball, and I don't care who knows."

Then there was the Facebook group "Hernando Haters" asking to rate her attractiveness, plus an anonymous email calling her a "waste of space." And this text arrived on her 16th birthday: "Wow, you're still alive? Impressive. Well happy birthday anyway."

It wasn't until Sarah's mom, who had access to her daughter's online passwords, saw the messages that the girl told her everything.

More young people are reaching out to family members after being harassed or taunted online, and it's helping. A poll released Thursday by The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research and MTV found incidents of "digital abuse" are still prevalent but declining somewhat. It found a growing awareness among teenagers and young adults about harm from online meanness and cyberbullying, as well as a slight increase among those willing to tell a parent or sibling.

"It was actually quite embarrassing, to be honest," remembers Ball, now an 18-year-old college freshman. But "really, truly, if it wasn't for my parents, I don't think I'd be where I'm at today."

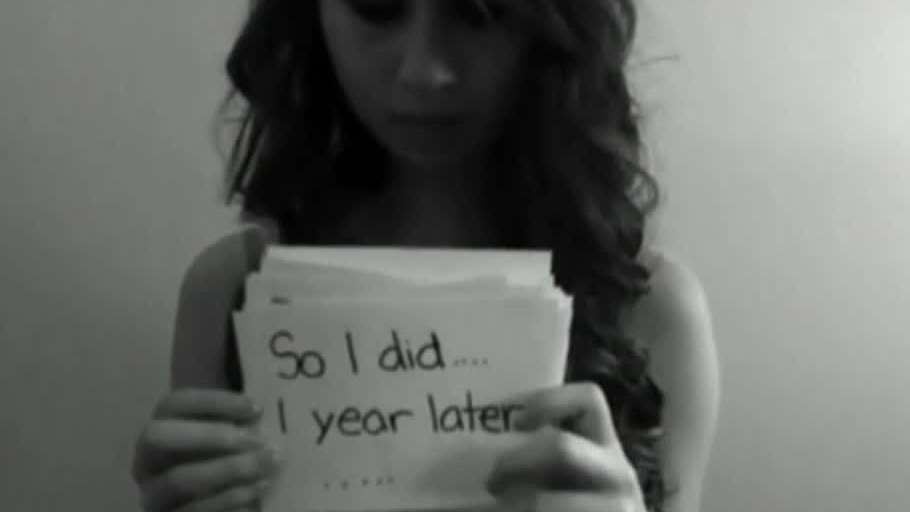

The survey's findings come a week after two Florida girls, ages 12 and 14, were arrested on felony charges for allegedly bullying online a 12-year-old girl who later killed herself by jumping off a tower at an abandoned concrete plant.

The AP-NORC/MTV poll found that some 49 per cent of young people ages 14 through 24 in the U.S. said they have had at least one brush with some kind of electronic harassment, down from about 56 per cent in 2011. Of those who have encountered an incident, 34 per cent went to a parent, compared with 27 per cent just two years ago. And 18 per cent -- up from 12 per cent in 2011 -- asked a brother or sister for help.

"I feel like we're making progress," said Sameer Hinduja, co-director of the Cyberbullying Research Center and professor at Florida Atlantic University. "People should be encouraged."

When asked what helped, 72 per cent of those encountering digital abuse responded that they changed their email address, screen name or cell number and it helped, while 66 per cent who talked to a parent said it helped too. Less than one-third of respondents who retaliated found that helpful, while just as many said it had no effect, and 20 per cent said getting revenge actually made the problem worse.

Girls were more likely than boys to be the targets of online meanness -- but they also were more likely to talk to reach out for help.

The poll also indicated that young people are becoming more aware of the impact of cyberbullying. Some 72 per cent, up from 65 per cent in 2011, said online abuse was a problem that society should address. Those who think it should be accepted as a part of life declined from 33 per cent to 24 per cent.

Hinduja credits school programs that are making it "cool to care" about others and increased awareness among adults who can help teens talk through their options, such as deactivating an account or going to school administrators for help in removing hurtful postings.

That was the case for Ball, whose parents encouraged her to fight back by speaking up. "They said this is my ticket to helping other people," she said.

With their help, Ball sent copies of the abusive emails, texts and Facebook pages to school authorities, news outlets and politicians, and organized an anti-bullying rally. She still maintains a Facebook site called "Hernando Unbreakable," and she mentors local kids identified by the schools as victims of cyberbullying.

She said she thinks if other teens are reaching out more for help, it's as a last resort because so many kids fear making it worse. That was one reason Jennifer Tinsley, 20, said she didn't tell her parents in the eighth grade when another student used Facebook to threaten to stab and beat her.

"I didn't want them to worry about me," Tinsley, now a college student in Fort Wayne, Ind., said of her family. "There was a lot of stress at that time. ... And I just didn't want the extra attention."

According to the Cyberbullying Research Center, every state but Montana has enacted anti-bullying laws, many of which address cyberbullying specifically. Most state laws are focused on allowing school districts to punish offenders. In Florida, for example, the state Legislature this year passed a provision allowing schools to discipline students harassing others off campus.

In Florida's recent cyberbullying case, the police took the unusual step of charging the two teen girls with third-degree felony aggravated stalking. Even if convicted, however, the girls were not expected to spend time in juvenile detention because they didn't have criminal histories.

The AP-NORC Center/MTV poll was conducted online Sept. 27 through Oct. 7 among a random national sample of 1,297 people between the ages of 14 and 24. Results for the full sample have a margin of sampling error of plus or minus 3.7 percentage points. Funding for the study was provided by MTV as part of its campaign to stop digital abuse, "A Thin Line."

The survey was conducted by the GfK Group using KnowledgePanel, a probability-based online panel. Respondents were recruited randomly using traditional telephone and mail sampling methods. People selected who had no Internet access were given it for free.