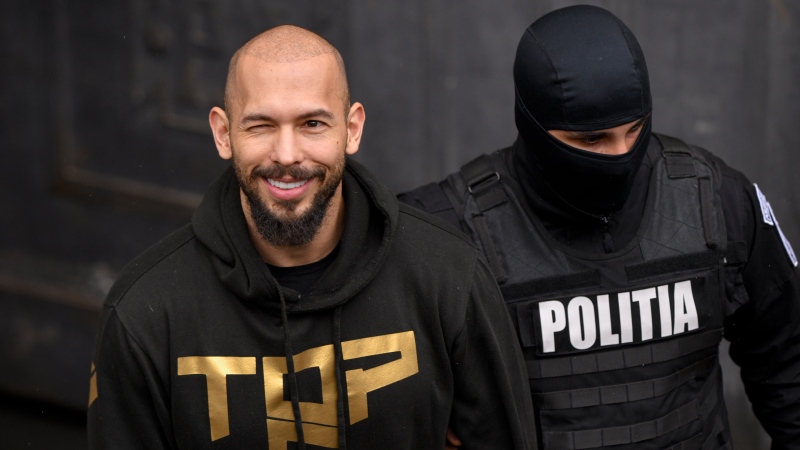

Ahmad Muna comes from a prominent Arab family in East Jerusalem, a young man who grew up surrounded by books and privilege. He has a business degree from Kent University in England and drives a scooter to work, two kilometres of weaving and dodging through Jerusalem traffic.

That recently included going through a new checkpoint less than a hundred metres from the family compound. On the day the checkpoint went up, it took Ahmad an hour and a half to travel a distance that would normally take five minutes. It’s an annoyance, among many annoyances Arabs feel under Israeli occupation. But Ahmad Muna, 24 years old, wearing jeans and a T-shirt, takes a philosophical approach.

"I think the State of Israel has to decide," he says. "Do you want us in, or do you want us out?"

We’re standing on the rooftop of the compound, in bright sunshine, taking in the view. On one side, I see an Israeli flag; Ahmad points out a long stone building that looks like a dormitory. It’s a settlement, he says, occupied by right-wing Jews who have taken over the property and are slowly encroaching on the Arab neighborhood below; his neighborhood. In the other direction, neat rows of bleached Jewish graves cascade down the Mount of Olives, white, white and spectacular against the dark blue sky. Above it all, floats a military observation balloon that I assume is watching us, but not only us.

"I don’t really see light at the end of the tunnel," he says. "I'm 24 years old and I don’t see a horizon for hope." That's a depressing way to look at life when you haven’t even had your 25th birthday. "I want to see a solution during my lifetime," he says. "I don’t want to get married and have kids. I don’t want them to live under occupation." I wonder if he’s talked to his father about this. Or if he has a girlfriend.

I ask him the same question I’ve asked other young Palestinians, trying to understand the motivation behind the latest violence. Terrible violence. Running at Israelis with kitchen knives. Using a truck as a battering ram. What’s behind a 13-year-old Arab boy trying to murder a 13-year-old Jewish boy at a candy store? Many of the attacks were carried out by residents of East Jerusalem, who have a status that Palestinians in the West Bank can only envy.

So, here's what Ahmad Muna has to say:

"Some people find it unbearable. Some people get to their limit and think, what’s been taken by force can only be taken back by force."

To be remembered in this long bloody struggle, Palestinians accuse Israelis of routinely using military domination and collective punishment as weapons of oppression.

Ahmad, who will one day take over his father's bookstore and stationary business, is against violence. From my perspective, he's too middle class, too protected, to get involved in clashes with the army. (A few days before, another young Palestinian from Jerusalem told me his mother would kill him if she found out he was throwing stones at Israeli soldiers.)

"With every period of violence," says Ahmad,"we have ended up worse than when we started. Every single time. Going back to 1948. I don’t think it’s the answer today."

He also doesn’t believe putting up concrete barriers will stop Palestinians who are intent on attacking Israelis. A lot of his Jewish neighbours would agree with that. "They know they are risking their lives, and mostly will be shot dead," he says. "And why would somebody do that? It’s just because they’ve lost hope. They’ve got nothing to lose."

He uses a term I’ve never heard before. "Mature occupied."And he wants to make sure I know where he's coming from: he blames Israel, not the Palestinians for the situation they face.

"We understand occupation today. We understand the behavior of occupation, a lot more than we used to. We know what to expect. But I also think we need to be smarter as Palestinians in the way we tackle it."

There are strong but beautifully crafted steel doors at the entrance to the Muna family compound. Ahmad puts on a black helmet, rides out the gate on his scooter and heads for the checkpoint. The Israeli guards barely pay attention as he glides around the concrete barriers and heads up the hill towards the Old City. Days earlier they made him pull up his shirt and pant legs, searched his scooter for hidden weapons. Compared to what it was, compared to what it could be, today was easy. He waves and carries on.