Every minute of every day, malaria takes the life of a child somewhere in the world.

The mosquito-borne disease is endemic in most tropical and sup-tropical areas, but until now, the only ways to ward it off were through insecticides, bed nets and anti-malarial pills.

Now, there's growing hope that the world's first malaria vaccine could soon be available to countires that need it most, offering a new tool in the fight.

British drugmaker GlaxoSmithKline has just released clinical trial data that shows a vaccine they developed significantly cuts cases of the disease in children. The company says it will now seek regulatory approval for the vaccine, known for now as RTS,S, so that the most affected countries could begin using it by 2015.

Malaria causes an estimated 219 million infections a year. Many adults get infected multiple times and develop some immunity, but the disease kill 660,000 people annually, most of them young children and most of them in sub-Saharan Africa.

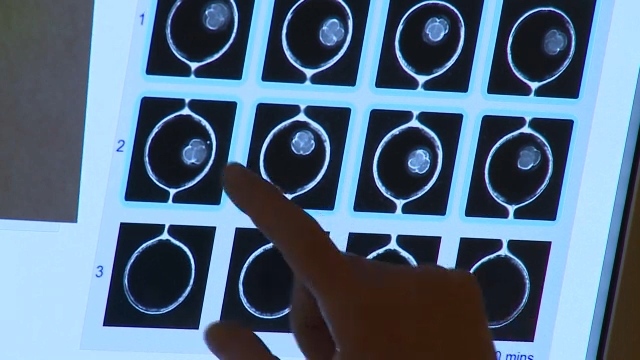

The latest data comes from a study of more than 15,000 children in 11 African countries. It shows that three doses of GSK's vaccine over an 18-month period cut the number of malaria cases in young children by half. In infants, it reduced the number of cases by approximately one quarter.

"Based on these data, GSK now intends to submit, in 2014, a regulatory application to the European Medicines Agency (EMA)," the company said in a statement. The trial results have not yet been published in a peer-reviewed journal.

Malaria causes an estimated 219 million infections a year. It is also linked to the deaths of 660,000 people annually, mainly young children in the poorest parts of sub-Saharan Africa.

GSK has been working for three decades to develop a vaccine against malaria. But efforts have been complicated because malaria is caused not by a virus or bacterium, but by a complex parasite, known as Plasmodium, that includes many constantly-evolving species.

The RTS,S vaccine works by taking part of an already-existing vaccine for hepatitis B and adding in a protein from Plasmodium falciparum, the most deadly species of the malaria parasite and the species that causes the overwhelming majority of infections in Africa.

The resulting vaccine isn't perfect, but researchers are excited nevertheless.

The clinical trial found that the vaccine's effectiveness was about 65 per cent in babies within six months of vaccination, but that the effectiveness waned over time. Data released from the study earlier this year found RTS,S protected only 16.8 per cent of children over four years.

But the World Health Organization says the vaccine could be a tool to be used in "addition to, not a replacement for" other malaria control measures, such as insecticides, mosquito nets, and anti-malaria drugs.

The non-profit PATH Malaria Vaccine Initiative has been helping to develop the vaccine along with GSK, and receives much of its funding from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation to MVI.

GSK has promised that it will price the vaccine at cost, plus a 5 per cent profit margin, if it receives regulatory approval. That margin would then be reinvested in further malaria research.

David Kaslow, vice president of product development at PATH said he hoped the vaccine could help boost anti-malaria efforts.

"Given the huge disease burden of malaria among African children, we cannot ignore what these latest results tell us about the potential for RTS,S to have a measurable and significant impact on the health of millions of young children in Africa," he said in a statement.