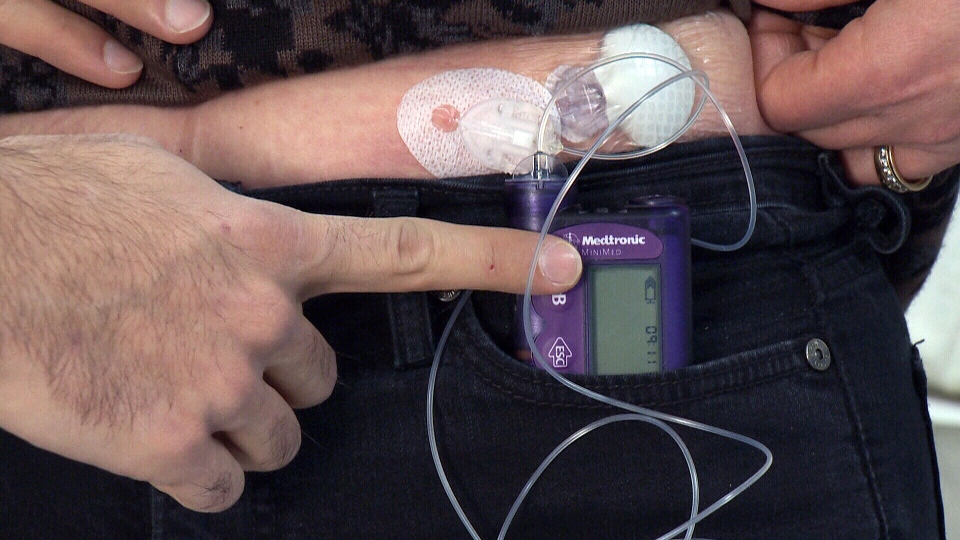

An “artificial pancreas” that constantly monitors glucose levels to ensure timely delivery of insulin is more effective at managing type 1 diabetes than a traditional insulin pump, new Canadian research has found.

Researchers at the Institut de Recherches Cliniques de Montreal say their dual-hormone artificial pancreas improved glucose levels and lowered the risk of hypoglycemia in 15 patients with type 1 diabetes.

Their study found that glucose control had improved by 15 per cent over the study period, while an eight-fold reduction in the risk of hypoglycemia was also noted.

Type 1 diabetes is a chronic disease that occurs when the body does not produce enough insulin, which leads to dangerously high blood glucose levels.

Keeping blood glucose, or blood sugar, levels in check with insulin injections or a pump is key to preventing long-term complications associated with high blood glucose, such as blindness or kidney failure. Treatment also helps prevent against hypoglycemia, when a patient’s blood glucose is so low that it can cause him or her to become confused or disoriented, or even lose consciousness.

“We have hope to be close to the improvement of treatment (less high blood glucose and less low), which would be a tremendous improvement in patients’ lives,” Dr. Remi Rabasa-Lhoret, director of the obesity, metabolism and diabetes research clinic at the IRCM, told CTV News. “And less complications, which is very exciting for doctors and patients.”

The researchers said the artificial pancreas system is based on an intelligent algorithm, which constantly monitors the patient’s changing glucose levels to recalculate the required dose of insulin.

While many diabetes patients already use a conventional insulin pump to control their disease, they are required to regularly check the pump’s sensor themselves and then adjust the pump accordingly.

Researchers liken the algorithm to a car’s GPS system, which constantly recalculates directions according to the car’s movements.

“Approximately two-thirds of patients don’t achieve their target range with current treatments,” Rabasa-Lhoret explained in a statement.

“The artificial pancreas could help them reach these targets and reduce the risk of hypoglycemia, which is feared by most patients and remains the most common adverse effect of insulin therapy.”

The researchers note that the system can also deliver glucagon, which can raise glucose levels when they are too low.

For the current research, patients were admitted to the IRCM’s research facility for two 15-hour visits: one in which they received the standard pump therapy and the other in which they were treated by the dual-hormone artificial pancreas. Researchers monitored their blood glucose levels as they exercised on a stationary bike, ate an evening meal and a bedtime snack, and as they slept.

Patient Evelyne Pytka is one of the more than nine million Canadians the Canadian Diabetes Association estimates has diabetes or prediabetes.

She was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes at age 31, and her life quickly became about consistent meals, testing her blood several times a day and injecting insulin.

She tested the artificial pancreas overnight as part of the study, and found it liberating to be able to go hours without checking her blood.

The artificial pancreas allowed her to sit down at dinner and “for the first time in 25 years, I didn’t have to test my blood sugar, I didn’t have to calculate my food. I could just eat. And I had forgotten what that was like.”

The findings are published in the Canadian Medical Association Journal.

Rabasa-Lhoret said that researchers are hoping to conduct clinical trials that test the system for a longer period of time and across a broad age group.

Rabasa-Lhoret said he has a waiting list for patients who wish to participate in the study.