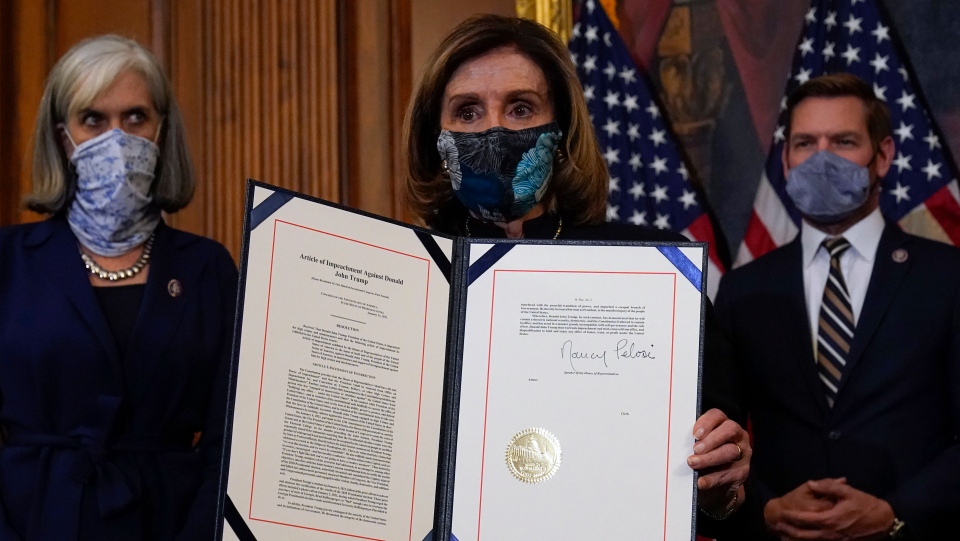

TORONTO -- With just days left before the end of U.S. President Donald Trump’s presidency, the House of Representatives voted to impeach Trump for a historic second time Wednesday, citing “incitement of insurrection” after a mob of supporters stormed the U.S. Capitol one week ago.

At the same time, the FBI has been making arrests across the country relating to the riots, prompting some to wonder whether Trump would try to squeeze in more pardons before his term is up, including pardoning his supporters, his family, and even himself.

Trump’s presidency has raised legal questions around pardons previously never tested in federal courts: the constitutionality of a self-pardon, for example, remains unclear since no president had ever attempted it before, with legal scholars divided on how to interpret the law.

Does Trump’s impeachment change anything when it comes to issuing pardons?

In Article II, Section 2 of the U.S. Constitution, it states that the president “shall have power to grant reprieves and pardons for offenses against the United States, except in cases of impeachment.”

But legal experts appear divided in what the clause “except in cases of impeachment” means.

“The conventional wisdom and centuries of treatises and textbooks tell us that when the Constitution says that the president can pardon ‘except in cases of impeachment’ means that the criminal process and the impeachment process are separate, and the president can only pardon crimes,” Brian Kalt, an expert on constitutional law and presidential history, and a law professor at Michigan State University, told CTVNews.ca in an email.

“He can’t stop an impeachment or undo an impeachment conviction, but he can still pardon any related crimes.”

With the House voting 232-197 to impeach the president, a two-thirds majority is still needed in the Senate in order to convict and remove Trump, the only U.S. president ever to be impeached twice. But the earliest a Senate trial would begin is next Tuesday, right before president-elect Joe Biden’s inauguration.

Kalt explains that Trump retains all of his powers until he is convicted or his term ends, meaning, “he can still issue pardons -- whether related to his impeachment or not -- while he is impeached.”

Kalt noted that former president Bill Clinton pardoned 34 people between his impeachment on Dec 19, 1998 and his acquittal on Feb 12, 1999.

“Nobody batted an eye at that because, again, the standard reading of the impeachment exception to the pardon power … is uniformly understood and accepted.”

Based on Clinton’s example, Trump could still issue pardons during his final week in office. Prior to his impeachment, he had already discussed issuing pardons for himself and his children, according to a CNN report this week, citing multiple sources. The report noted Trump, his allies and family members who partipated in the rally at the Capitol could potentially face legal exposure following the riots.

Trump could, in theory, issue a blanket pardon that covers himself and his children up until the time he leaves office, according to CNN’s source. Another source indicated that Trump may extend it to others outside the family as well, including Trump’s personal lawyer, Rudy Giuliani.

Already Trump’s previous pardons -- which have included four American men convicted of killing Iraqi civilians, his former campaign manager Paul Manafort, ex-adviser Roger Stone, and his son-in-law’s father, Charles Kushner -- have generated enormous outrage.

WHAT CAN BE PARDONED?

While pardons can not be overturned by the courts or Congress, the power to pardon someone is not unlimited, according to numerous legal articles around the subject.

A presidential pardon can not be used for crimes committed under state law.

While there is general agreement that a president can not grant pardons for crimes not yet committed, they can be issued for “conduct that has not resulted in legal proceedings,” according to Reuters.

In an 1866 Supreme Court decision, it stated that “the power of pardon … extends to every offence known to the law, and may be exercised at any time after its commission, either before legal proceedings are taken or during their pendency.”

PARDONS RELATING TO TRUMP’S IMPEACHMENT

Despite the pardons issued by Clinton, and Kalt’s view that Trump can still issue them even if they are related to the impeachment, others have a different interpretation of the constitutional clause.

“One of the key things that the impeachment … will do is really limit his ability to pardon. In cases of impeachment, a presidential pardon is not operative,” Stephen Farnsworth, a political science professor with the University of Mary Washington, told CTV News Channel.

“If you were worried -- or if some of the Democrats were worried -- about President Trump basically pardoning everyone involved in this matter, that’s going to be a much more difficult legal road to do going forward.”

A Washington Post analysis by two professors and experts on the U.S. presidential office said that only Congress, not the Supreme Court, can decide whether the president “can pardon himself or others directly connected to the high crimes for which he is impeached.”

“We and other legal scholars understand the clause to mean ... the president cannot pardon himself or others in matters directly associated with his own impeachment,” wrote Corey Brettschneider, a professor of political science at Brown University and Jeffery K. Tulis, a professor of government at the University of Texas at Austin.

“Under this view, Trump could issue no pardon for himself or the insurrectionists for criminal charges related to the events of last week.”