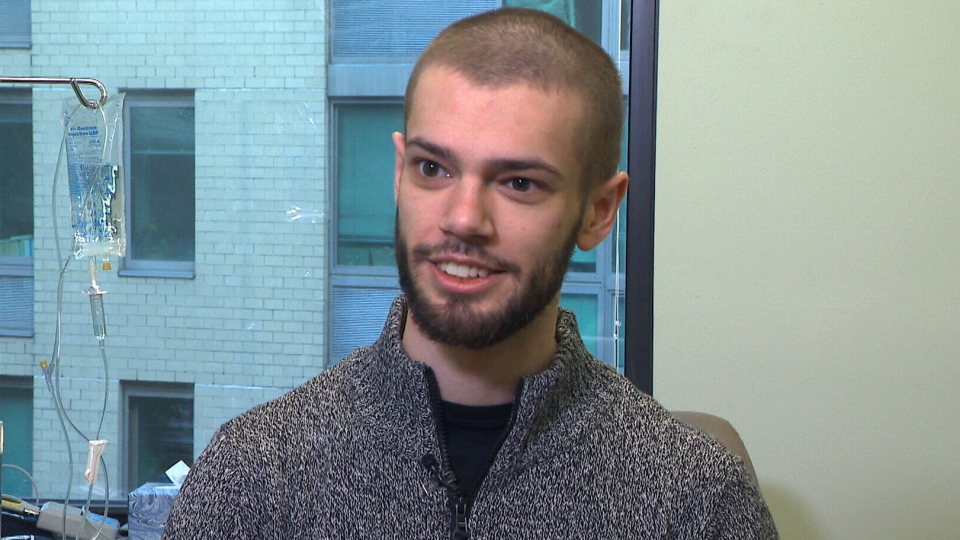

William Jamieson is only 23, but he’s already spent almost one-third of his life battling severe depression.

Once a top student and athlete with a large group of friends, the young Ottawa man fell into a depression at age 16 that he couldn’t shake.

“It got pretty bleak,” he says. “In terms of energy, I just couldn't get out of bed. I couldn't eat. I didn't have the energy to eat. I was wasting away."

“I kind of kept myself in the dark. That goes to how you see the world,” he adds.

He tried at least 10 medications and received electric shock therapy -- but nothing worked.

Watching his son sink further into his depression left William’s father Charles desperate to help.

"There was nothing more they (the doctors) could do, and as a parent, that is not what you want to hear, because the depths of William's depression were as dark and black as you can imagine," Charles says.

Fearing for his son’s life, the elder Jamieson went online.

"I typed in Google: ‘breakthrough depression treatments,’ and ‘ketamine’ came up," he says.

Though probably best known as the party drug “Special K,” ketamine has been used as an anesthetic and painkiller for decades. But in recent years, it’s been explored as a treatment for depression.

Researchers say the drug can lift depression and suicidal thoughts in patients with even one treatment.

Doctors at the Royal Ottawa Mental Health Centre have been using intravenous ketamine on patients with treatment-resistant depression and say they are seeing promising results.

Ketamine isn’t approved by U.S. regulators to treat depression, but hundreds of private health clinics have been offering it off-label. Jamieson now travels from his home in Ottawa to New York City every six weeks to get infusion from anesthesiologist Dr. Glen Brooks.

The darkness began to lift two days after the first treatment, William says.

“It feels like there is a loosening of the fist that is inside of your head.”

His father Charles grows emotional thinking about that weekend.

“I say, ‘Will, how are you feeling?’ He says, ‘Dad, it is gone. The depression is gone. The colours are brighter.’ I will never forget those words. ‘The colour is brighter. The fog is gone,’” he says.

Dr. Brooks has used ketamine for 35 years to treat neuropathic pain. After reading research on using of ketamine for depression, he began to offer the drug to patients with long histories of post-traumatic stress disorder and other mood disorders, charging up to US$400 per infusion.

Many of his patients have tried multiple medications and electroshock therapy and have not responded.

“So this is generally more of a last stop than a first stop,” he explains.

He says the improvements are often rapid and dramatic.

“What patients report is a sense of calmness and wellbeing that comes over them,” he explains.

Dr. Brooks believes that for suicidal patients, “ketamine saves lives every day.”

“I don't think anything is as effective as ketamine has been,” he says.

In Canada, many psychiatrists are excited to better understand how ketamine works in the brain, but others are urging patience until more is known about the drug’s possible side-effects, including elevated blood pressure, blurred vision, and bladder inflammation.

“We don't know who is more prone to the side effects or indeed, the long-term consequences of the side effects,” says Dr. Sidney Kennedy, the Arthur Sommer Rotenberg Chair in Suicide and Depression Studies at St. Michael’s Hospital in Toronto.

But Dr. Brooks says patients should be able to access a drug that could save their lives.

“In my experience of treating over 1,500 patients, I see no reason for any patient to wait, especially if they are critically ill with their mood disorder,” he says.

Charles Jamieson thinks ketamine should be more widely available in medically supervised settings. Until it is, he will pay for his son to get the drug in the U.S.

“I have got my son back and I know he will have the life that he wants to make. He has an opportunity that he would not have had without ketamine,” he says. “Without ketamine, it would have been a terrible, different story.”

With a report from CTV medical specialist Avis Favaro and producer Elizabeth St. Philip