A new report concludes that transvaginal mesh products used to help treat incontinence and organ prolapse were approved on the basis of weak evidence and “may have exposed women to avoidable harms.”

Researchers writing in the BMJ medical journal say regulatory “failings” enabled the devices to be brought to market without good evidence to show the products were safe.

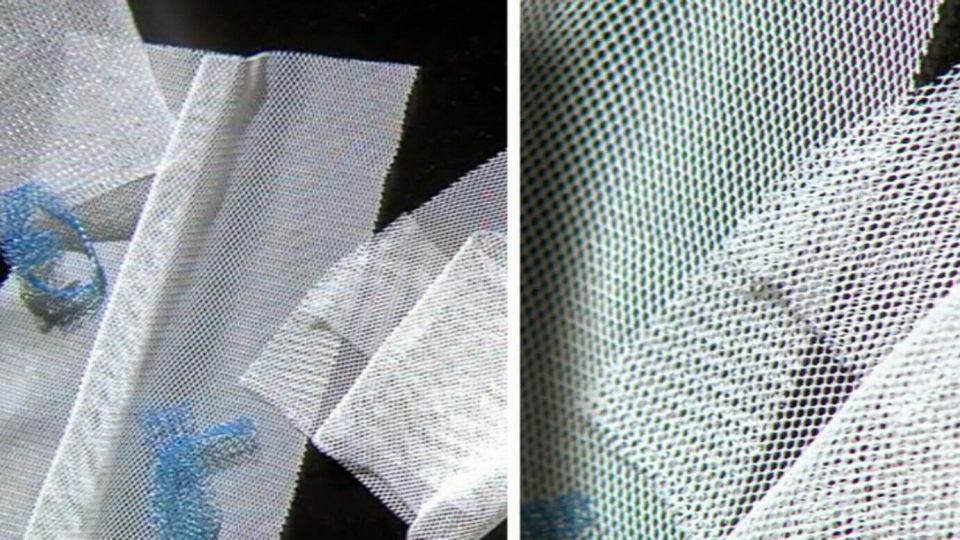

Vaginal mesh has been used for close to 20 years to treat urinary incontinence as well as pelvic organ prolapse (POP), a condition in which the muscles that hold pelvic organs become weak from childbirth or age.

While thousands of women have had no problems with the mesh, thousands of others have complained about serious complications, including painful and seemingly never-ending bacterial infections.

More than 100,000 lawsuits have been launched over the meshes. CTV News has spoken with many of the women behind the Canadian lawsuits, including Chrissy Brajcic, of Windsor, Ont., who suffered numerous infections even after having her mesh implant removed.

Brajcic died last week after being treated for sepsis. A coroner has yet to determine whether her mesh implant played a role in her death.

In the new BMJ paper, a research team from Oxford University's Centre for Evidence Based Medicine looked at how 61 mesh devices received approval from the Food and Drug Administration.

They found that in the U.S., the FDA initially considered transvaginal meshes as equivalent to mesh products already on the market for other uses. That allowed them to be approved and classified as “Class II devices (lower risk).”

The British researchers say they could not find evidence that manufacturers submitted data from clinical trials that tested the meshes specifically for use in POP or incontinence.

“Clinical trials evidence did not form part of the approval process, and when trials were conducted, they occurred a considerable time later (up to 14 years),” the authors write.

The authors conclude that there was not enough evidence to approve the mesh products and “when evidence has been forthcoming, it has often emerged too late to inform clinical practice.”

Dr. Vladimir Iakovlev at Toronto’s St. Michael’s Hospital, who has researched some of the complications of transvaginal mesh, notes that the regulatory approval process in Canada is typically based on FDA analysis.

“We use the same meshes (in Canada) and the complications with patients are exactly the same,” he told CTV News.

The researchers who traced the FDA approvals of the 61 mesh products found the approvals were often based on “equivalence” to two existing products approved in 1985 and 1996.

One of those products was called the Protegen sling, which was made from polyester. But newer transvaginal mesh is typically made from polypropylene – a significant difference “that should have negated the use of equivalence," the authors say.

Polypropylene has a tendency to shrink significantly after implantation, they write, which can lead to serious complications, such as tissue erosion and organ perforation.

Removing the mesh once problems arise is not simple, the authors note, since the meshes are designed to integrate into the nerves and blood supply of nearby tissues.

Iakovlev says there need to be a better regulatory approval system for new medical devices such as transvaginal mesh.

“We have to develop a better approach for how to assess their safety… because these devices are implanted for life; they’re permanent,” he said.

The report authors say they would like to see national registries of “invasive devices,” that would detail the evidence behind the devices and keep track of any complications.

Iakovlev would like to see the same and says similar registries are needed for other devices such as hip replacements, implanted defibrillators.

“This study shows we need to monitor these devices. We need to slowly introduce them to the market. And that can only be achieved with nationwide registries.”

With a report from CTV medical specialist Avis Favaro and producer Elizabeth St. Philip