TORONTO -- The start of school is typically a stressful time for families, but none more so than this year as families try to adjust to a new reality in which even the slightest sniffle or minor headache could mean COVID-19 tests, days of isolation, and interruptions to education and work.

Now that schools and daycares across the country have reopened and welcomed students back, coronavirus cases numbers have crept back up in certain regions, forcing children and staff to return home to get tested for the virus and self-isolate.

In some cases, entire schools have shut down in response to rising case counts, such as in Montreal where one private high school, Herzliah High School, suspended in-person learning for two weeks after more than a dozen students and staff tested positive for COVID-19.

While medical experts have been warning the public for months there would be a second wave of cases in the fall, the practical implications for families are only just being realized.

Dr. Andrew Morris, an infectious disease specialist at the University of Toronto and the Sinai Health system who contributed to a report by medical experts on the return to school, said public health authorities are working closely with school boards to find the right balance of teaching students while keeping them and their families safe.

“It’s really complicated. There aren’t, unfortunately, any simple fixes right now,” he told CTVNews.ca during a telephone interview on Thursday.

SYMPTOM SCARES

The confluence of coronavirus, flu, and allergies has made identifying symptoms for each a tricky task with most schools and daycares erring on the side of caution and mandating that children who exhibit any symptoms, whether it be a cough or stomach ache or runny nose, to stay home and get tested for COVID-19.

While the guidance varies across provinces and regions, generally, families have been asked to assess their children’s symptoms before taking them to school or daycare and to keep them home if there’s any sign of sickness.

“The advice in many ways hasn’t really changed,” Morris said. “Sick kids shouldn’t be going to school.”

If the child develops symptoms during the day, most schools and daycares are asking families to take them home and have them tested for coronavirus or self-isolate for two weeks before they will be allowed to return.

That was the case for Denise Faubert’s 10-year-old daughter who was sent home from her Ottawa elementary school on Monday because she had developed a headache.

“My daughter was sent home for a headache because she was dehydrated because they’re in a portable and they don't want to drink a lot because they don't want to go into the school to go to the bathroom,” she explained.

“We got home, literally an hour-and-a-half later, after a little Tylenol, she was fine. Like literally fine, jumping, going on the internet, going outside.”

Despite her daughter’s improvement, Faubert said she was forced to pick up her 15-year-old daughter from a nearby high school and bring her home as well. The next day, she drove her younger daughter to a testing clinic in Casselman, Ont., located 50 kilometres outside of Ottawa, for the test because the lineups in the city were too long.

On Wednesday night, Faubert said her daughter’s test results came back negative and both of her children were allowed to return to school the next day after she sent the results to both schools.

“The schools are so paranoid,” she said. “The guidelines for what they’re required to look for…They're just too afraid of keeping anyone at school.”

TESTING CONCERNS

Faubert’s concerns were echoed by other parents who spoke with CTV News about their worries for what the school year will look like if they have to keep picking up their child, getting them tested, or self-isolating every time they have exhibit a symptom.

Sharon Cheng-Ghafour said she felt most anxious about having to take her 20-month-old twins to a Toronto hospital for COVID-19 testing after one of them woke up on Monday morning with a dry cough. Even though she suspected it was only a minor irritation and not the virus, she decided to keep the twins home as a precaution and informed their daycare.

Cheng-Ghafour said the daycare operator told her the twins wouldn’t be able to return unless they received a negative test result or after 14 days. She said she wished there was a pediatric assessment centre where she could have taken her children instead of the ER, but the drive-thru testing centres don’t test children under the age of two.

“You don’t want the ERs to be loaded with these parents to try to prove that their kids don't have COVID,” she said.

With long lineups and not enough sites in some regions, Morris said the testing backlog poses a risk to the school system because families may become more reluctant to report symptoms if they know they will have to go through an ordeal to have their child tested.

“The fact that we are having people wait in line for hours, the fact that we don't have the capacity at the moment, and for a variety of means, to do all the testing that is being demanded, that’s a huge risk to our fight against COVID,” he said.

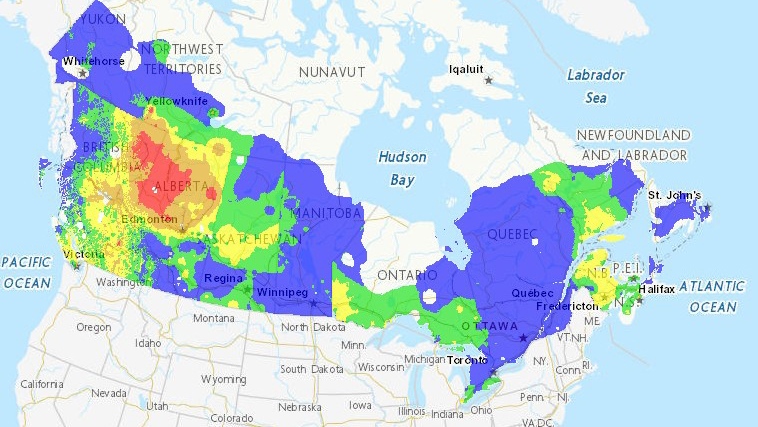

In an effort to respond to the increasing demand for tests, provinces are scrambling to introduce more testing sites, such as at pharmacies in Ontario and Alberta, mobile clinics in Quebec, and an easier method of testing using a “mouth rinse gargle” in B.C. to speed up the process.

INTERRUPTIONS

All of the parents CTV News spoke said they were concerned about how they would be able to manage their schedules if they’re required to pick up their children, take them for a test, stay at home with them, and work at the same time.

“I don't know how it’s going to work in the future,” Cheng-Ghafour said. “If every time somebody has a sniffle or dry cough or something, we have to stay home for 14 days… I’m just in the process of opening a new practice and I'm thinking ‘I don't know how it’s going to work.’”

Miriam Beamish said she had to make a difficult decision about where to send her four-year-old son to school this year. The Toronto mother said she had to pick up her son from his kindergarten class at a private daycare in the city after he developed a runny nose.

She said her son didn’t end up having COVID-19 and he always has a runny nose at this time of year so he was able to return a few days later.

“I don't have somebody who to make these big decisions with. I have to make them all by myself and it's really hard to know what the right thing to do is,” she said. “It’s just such a scary, scary time.”

In addition to the disruption in parents’ lives, Gilda Benhamou, whose son attends the Montreal private high school that paused in-person learning, said she’s concerned about the impact on his education.

“I'm more worried about my son’s education,” she told CTV News Montreal on Thursday. “I think the school is going above and beyond and has done everything in their power to make sure the kids are safe.”

Morris said families will have to try to be adaptable as they can as public health guidance and school policies evolve over the course of the school year in response to virus’ spread.

“Things are going to change. They [families] are getting used to changes. They’re about to have more changes,” he said. “We need to learn to adapt. When you get more information, you need to be adaptable.”

With files from CTV News Montreal

Correction:

An earlier version of this article mistakenly stated that Miriam Beamish had a daughter and not a son. It also said she was having difficulty caring for them, which is not the case.