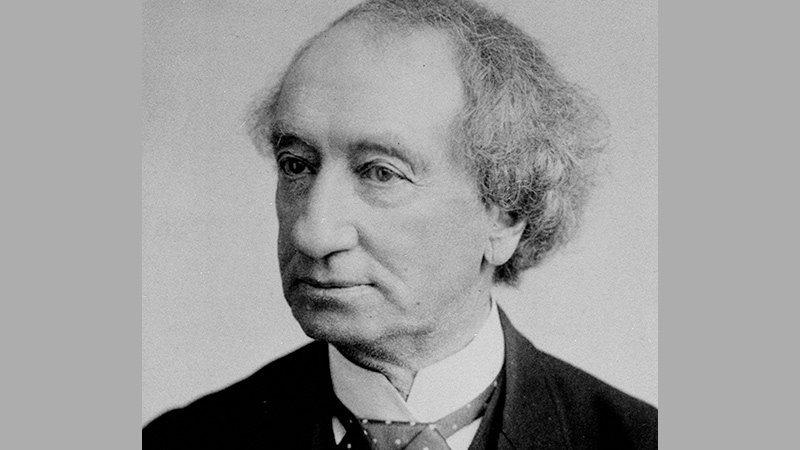

The Ontario city where Sir John A. Macdonald lived and worked for years is launching public consultations on the legacy of Canada's first prime minister in light of heightened scrutiny over his treatment of Indigenous people.

The City of Kingston said that starting next week, residents will get the chance to voice their opinions online and in person on Macdonald and his place in the community's history.

The public input will be used to develop a report on whether the city needs to offer re-interpretations of local exhibits, monuments and general historic programming in the future, said Jennifer Campbell, Kingston's manager of cultural heritage.

"What really sparked the need to have a more directed dialogue is our desire ... to think a little bit more deeply about how we unpack our histories, legacies and how they reflect the City of Kingston and our residents," Campbell said in an interview.

"We need to tell our histories and stories to be more inclusive of all of our residents."

Macdonald's role in establishing residential schools and limiting the mobility of Indigenous peoples has made him a polarizing figure. In 1883, he argued in the Commons for the removal of Indigenous children from their "savage" parents so they could learn the ways of white men.

The government-funded, church-run residential schools operated for more than a century. Indigenous children were ripped away from their families, usually starting in late September, and sent to schools where they endured widespread sexual, emotional and physical abuse.

The City of Victoria recently removed a statue of Macdonald as part of a reconciliation process with First Nations. In Montreal, a statue of the first prime minister was spray-painted red earlier this month, with an anti-colonial group claiming responsibility. A statue of Macdonald in Regina was also recently splashed with red paint.

Kingston, where Macdonald grew up and worked for years, has also seen protests related to the former prime minister, particularly around events that celebrated the bicentennial of his birth in 2015.

"Kingston has a lot of work to do to contemplate its relationship to Sir John A. Macdonald," said Laura Murray, an English professor at Kingston's Queen's University whose research has focused on Macdonald's memory in the city.

"I hope that Kingston is ready to really confront some of the serious effects that he had on Indigenous people."

Terri-Lynn Brennan, who identifies as Mohawk and British, said the consultations are a huge step forward for Kingston.

"I'm really happy they are taking these necessary steps to have a really good mirror up to themselves," said Brennan, a former inter-cultural planner for the city who produced a report with recommendations on how to approach Indigenous communities to build relationships.

"There's a lot of work ahead, but it's not just the City of Kingston," she added, saying many cities need to address their colonial past.

In addition to the consultations, Kingston is also currently reaching out to Indigenous communities for their thoughts on Macdonald -- an exercise that was started in response to recommendations from the Truth and Reconciliation commission.

The commission was established in 2008 to bring to light the abuses that occurred in residential schools and delivered a long list of recommendations in 2015.

The consultations in Kingston, which are expected to last six to eight months, come as the federal government looks at how to address concerns with figures like Macdonald.

Environment Minister Catherine McKenna said this month that she had tasked the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada to examine how issues with historical figures can be address thoughtfully. The board is also looking at ways to commemorate residential school sites and the history and legacy they left behind, in consultation with Indigenous groups.