DALLAS -- A Texas border town is working to restore what is believed to be the only remaining site that once helped process the millions of Mexicans who came to the U.S. as temporary guest workers under a program that started during the Second World War.

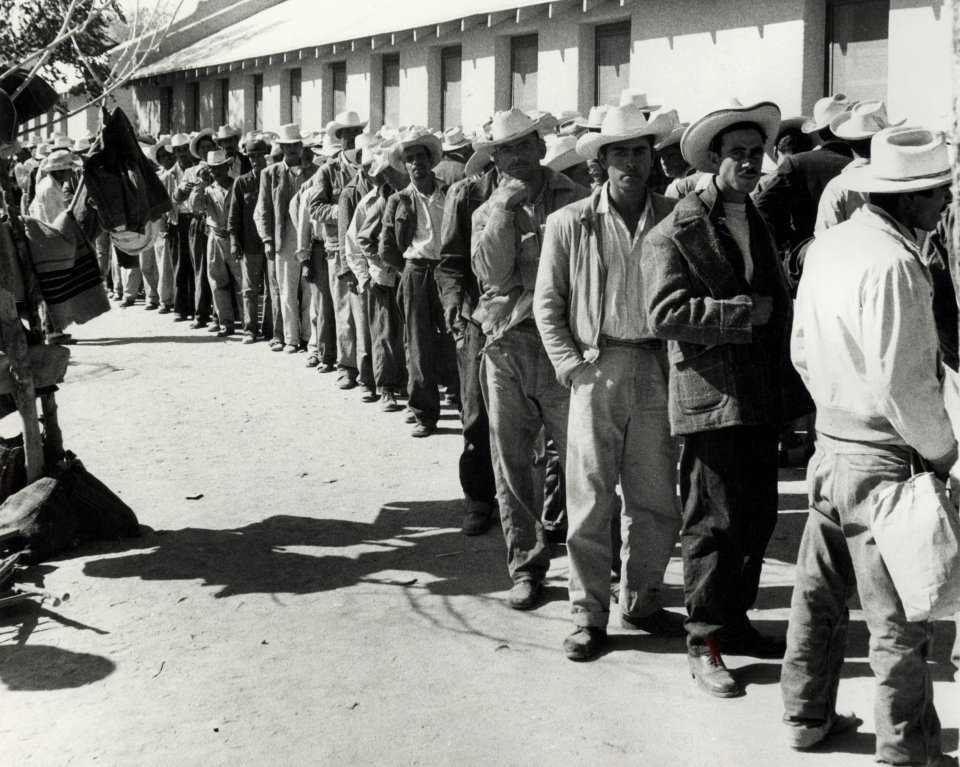

The crumbling white adobe buildings at Rio Vista Farm in Socorro, a town along the Rio Grande about 996 kilometres west of Dallas, were the arrival point for "braceros" -- Spanish for labourers -- who came to the U.S. to work on farms and railroads as part of a program in the middle part of the 20th century. Local officials and preservationists hope to turn it into a site that will tell the story of the workers and a largely forgotten program that lasted for about 20 years.

"These men left their families, left their communities with the hope of economic opportunity and often worked incredibly hard and in very difficult kinds of conditions," said Peter Liebhold, curator at the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C.

The effort to preserve the 102-year-old site as a sort of museum documenting a program that helped the U.S. get workers during the Second World War has gained new significance since President Donald Trump took office after promising to build a wall along the U.S.-Mexico border and step up deportation efforts.

Running from 1942 to 1964, it has been the United States' largest guest worker program, with an estimated 4.6 million short-term labour contracts issued to Mexican workers, with some coming through multiple times. The program did not provide a path to U.S. citizenship, although many braceros went on to become citizens, according to Liebhold.

Rio Vista Farm in Socorro was one of five processing sites for the braceros, who would have spent anywhere from several hours to a day there before being sent to their work sites.

Francisco Uvina, who was among the braceros who went through Rio Vista, wants "the good and the bad" of their story to be known. Uvina, now 83, eventually became a U.S. citizen and lives in Sunland Park, New Mexico.

The good part of being a bracero, he said, was the money the workers earned.

The bad was how he and the others were sometimes treated. Upon arrival at Rio Vista, workers were stripped and fumigated with a pesticide. The braceros also sometimes worked in difficult conditions. Uvina, speaking through a Spanish translator, recalled a work site where the bosses wanted the braceros to work even when it was so cold icicles formed. Pointing out that one can't wear gloves while picking cotton, he also noted that their barracks had no heat.

"It wasn't perfect and there were a lot of really sad and ugly parts to this story," said Sehila Mota Casper, a field officer with the National Trust for Historic Preservation. "But I think that it goes to show that when countries come together in a time of need, we can be stronger together."

The private non-profit trust is working with local officials on the restoration and is seeking stories of those who came through Rio Vista Farm when it operated as a bracero processing centre from 1951 to 1964.

"Of course, the interest in places like Rio Vista has only increased as the national conversation about immigration policy has intensified," said Stephanie Meeks, CEO of the trust.

Rio Vista was established in 1915 as a county poor farm, sheltering homeless and destitute adults and neglected and abandoned children. After serving as a bracero processing centre it was eventually purchased by the city. In recent years a couple of the buildings have served as a senior citizen centre.

The city has earmarked $1.1 million toward the site's restoration and federal, state and private grants have been awarded to help with the project. So far, the plan for the site includes placing a cultural centre and the city's first library on the site.

Among those with connections to the bracero program is Socorro's mayor, Gloria M. Rodriguez, whose father was a bracero. Although her dad didn't go through Rio Vista, Rodriguez hopes the site can draw attention to this little-known piece of U.S. history.

"The site is not visited very often. Maybe if we can preserve it a little bit better it will be," she said.