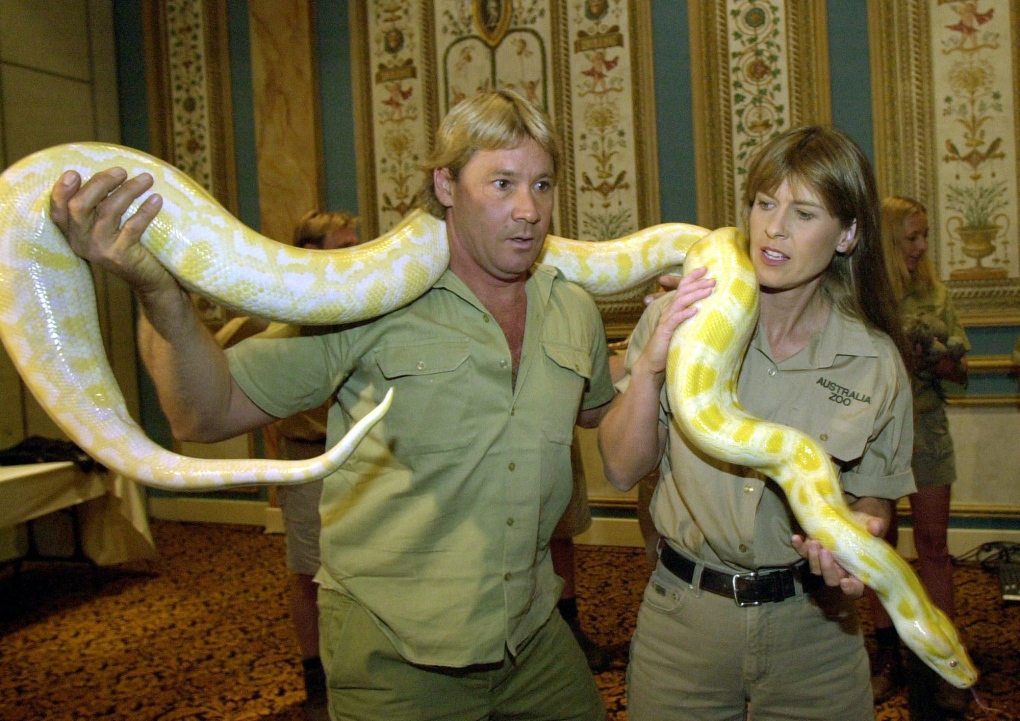

Steve Irwin, the legendary and seemingly invincible “Crocodile Hunter,” knew it was likely the end. He looked up at his cameraman, a gaping stingray barb wound in his chest, and said “I’m dying.”

Those were his only words -- his last -- before he died.

Irwin was fatally injured by a violent stingray attack in 2006 while shooting a documentary entitled “Ocean’s Deadliest” on the Great Barrier Reef.

Now the only man who witnessed Irwin death’s has spoken publicly about the incident for the first time in an interview with the Australian morning program Studio 10.

Irwin’s long-time cameraman Justin Lyons said the crew had been out on an inflatable boat in the Batt Reef in Queensland, Australia when they spotted a “massive” stingray swimming through the chest-high water.

Lyons said he and Irwin slipped out of the boat, briefly making a plan about how they would collect footage of the eight-foot-wide bull ray -- a type of stingray that gets its name from its distinct head shape.

After several minutes of shooting, Lyons said they stood up and decided “one last shot.” The plan was for Irwin to swim behind the stingray so Lyons could get a shot of the large creature swimming away.

“I had the camera and thought this was going to be a great shot,” Lyons said. “And all a sudden it (the stingray) propped on its front and started stabbing (Steve) with its tail. Hundreds of strikes in a few seconds.”

Those strikes were punctuated by a sharp barb at the end stingray’s tail, which plunged rapidly into Irwin’s chest.

“It went through his chest like a hot knife through butter,” Lyons said. “He thought it had punctured his lung, and he stood up out of the water and said ‘it’s punctured my lung.’ ”

Lyons said he believes the stingray had mistaken Irwin’s shadow for a tiger shark, one of its natural predators.

Blood and fluid began rapidly flowing out of Irwin. Within seconds, crewmembers on the inflatable reached the two men, and Irwin was pulled on board.

“He was in extraordinary pain,” said Lyons, adding that the stingray’s barb also contained venom. “He had an extraordinary threshold for pain, so I knew that when he was in pain, it must have been painful.”

Lyons said he kept talking to Irwin, telling him: “Think of your kids, Steve. Hang on. Hang on. Hang on.”

A father of two, Irwin’s son and daughter were just three and eight at the time.

“And he just sort of calmly looked up at me and said ‘I’m dying,’” Lyons said. “And that was the last thing he said.”

Lyons believes Irwin lost consciousness after that, though his eyes remained open.

Lyons said he clung to hope, believing at the time that the barb had punctured Irwin’s lung. It had actually pierced his heart.

Lyons said he performed CPR on Irwin for more than an hour before a medical team arrived.

“They pronounced him dead within ten seconds,” Lyons said.

The damage to his heart had been massive.

Lyons said that everything, from the attack to the CPR, was all captured on video. Irwin had made a rule that no matter who was injured, someone was to always keep filming; a second cameraman filmed Lyons' efforts to revive Irwin.

The footage has never been released, and Lyons said he doesn’t know what happened to it. He said he hopes it never airs, out of respect to Irwin’s family.

Lyons has continued working on documentaries since Irwin’s death, including on one called “E-Motion,” which explores how human emotions affect the human body.

He said he always thought that if an animal was going to kill Irwin, it wouldn’t be the dangerous crocodiles or sharks he was legendary at tracking down and handling.

“We always thought it would be a crazy, silly accident,” Lyons said. “And that’s what it was.”