LONDON -- The governor of the Bank of England on Wednesday waded into the delicate question of whether Scotland would be able to use the pound should it become independent, saying a successful currency union would require giving up some sovereignty.

Independence advocates say they want to continue to use the pound as the country's currency if the Scottish people vote for separation this year.

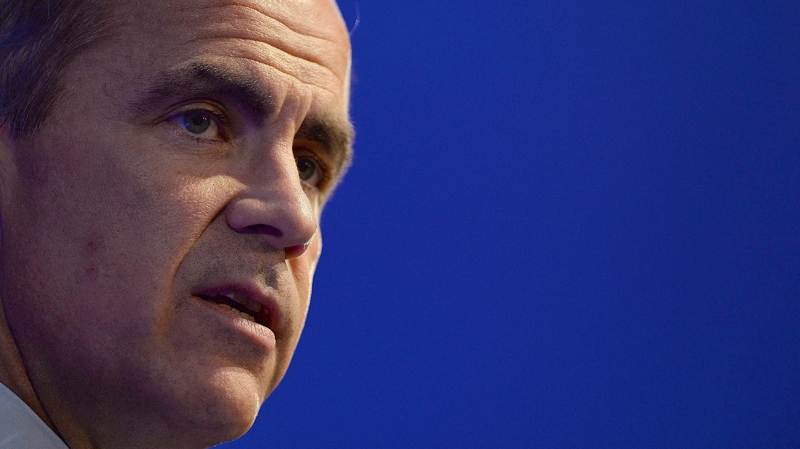

Mark Carney warned that successful currency unions still require some level of common fiscal policy and bank supervision. The recent debt crisis in the countries sharing the euro shows the risks of what can happen if those measures aren't put into place, he said.

"In short, a durable, successful currency union requires some ceding of national sovereignty," Carney said at a meeting in Edinburgh of the Scottish Council for Development and Industry.

Carney stressed it was up to the parliaments of Britain and Scotland to decide whether Scotland continues to use the pound in the case of independence. The Bank of England would implement whatever policy they chose.

"Decisions that cede sovereignty and limit autonomy are rightly choices for elected governments and involve considerations beyond mere economics," he said.

Carney's remarks are important because independence leader Alex Salmond, Scotland's first minister, has repeatedly stressed that the pound would remain the country's currency -- a selling point to his movement. While Scotland is part of the U.K., it has had its own Parliament since 1999 and makes its own laws in many areas -- but it is considering a full break.

Salmond's governing Scottish National Party supports independence, but the opposition Labour and Conservative parties oppose it. The U.K. would have to agree to a currency union for it to become reality.

Carney stressed, however, he was not taking a position on the vote and that he was simply offering information.

"This is a technocratic assessment of what makes an effective currency union between independent nations," he said.

The Scottish National Party quickly praised Carney's "serious and sensible analysis of how a currency union can work in practice.

"Ultimately, as Mr. Carney makes clear, a Sterling area is a matter for the two governments to agree," Scottish Finance Secretary John Swinney said. "Such a shared currency area is the common sense position as it is in the overwhelming interests of both Scotland and the rest of the U.K."

Such an agreement would not be simple, said Monique Ebell, an economist at the National Institute of Economic and Social Research who is working on the economic issues of Scottish independence. Countries in a monetary union agree to support each other -- and the U.K. economy would dwarf that of Scotland.

"Would a country the size of Scotland really be able to bail out the rest of the U.K.?," she said. "In theory, the insurance is a two-way street. In practice, it would likely be a one-way street."

Scotland votes on Sept. 18, and political battles in the run-up to the referendum have come in many ways other than straightforward pocketbook politics. British Prime Minister David Cameron has argued fiercely against it, saying among other things that people living in Scotland would pay an extra 1,000 ($1,600) a year in taxes. Salmond said Scots would actually pay less than they pay now.

Polls have consistently put support for independence at between 25 per cent and 30 per cent over the past three years, with support for remaining in the union at between 45 per cent and 50 per cent. But the number of undecided voters is significant.