WASHINGTON -- A deeply divided Supreme Court upheld the use of a controversial drug in lethal-injection executions Monday, even as two dissenting justices said for the first time they think it's "highly likely" the death penalty itself is unconstitutional.

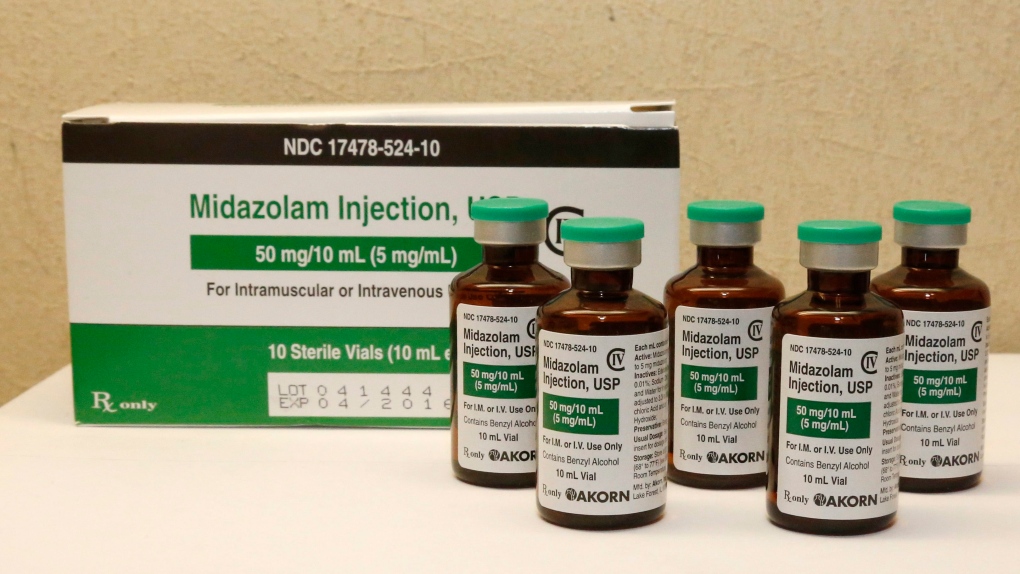

On their last day together until the fall, the justices voted 5-4 in a case from Oklahoma that the sedative midazolam can be used in executions without violating the U.S. Constitution's Eighth Amendment which prohibits cruel and unusual punishment.

The court also divided 5-4 in a case upholding independent commissions that draw congressional districts in Arizona, California and 11 other states in a bid to reduce partisanship in electoral mapmaking. By a similar margin, the court called into question first-ever limits on emissions of mercury and other toxic pollutants from power plants, in a ruling that said the federal Environmental Protection Agency failed to account for the cost of the regulations at the outset.

In addition, the justices agreed to hear an important case from Texas about the use of race in college admissions for its term that begins in October. The court also granted an emergency appeal from Texas abortion clinics to prevent the state from enforcing regulations that would close more than half the state's 19 clinics. The order suggests the court will add abortion regulations to its calendar for next term.

In the dispute over the lethal-injection drug, midazolam was used in Arizona, Ohio and Oklahoma executions in 2014. The executions took longer than usual and raised concerns that the drug did not perform its intended task of putting inmates into a coma-like sleep.

Justice Samuel Alito said for a conservative majority that arguments the drug could not be used effectively as a sedative in executions were speculative and he dismissed problems in executions in Arizona and Oklahoma as "having little probative value for present purposes."

In a biting dissent, Justice Sonia Sotomayor said, "Under the court's new rule, it would not matter whether the state intended to use midazolam, or instead to have petitioners drawn and quartered, slowly tortured to death, or actually burned at the stake."

Alito responded, saying "the dissent's resort to this outlandish rhetoric reveals the weakness of its legal arguments."

In a separate dissent, Justice Stephen Breyer said the time has come for the court to debate whether the death penalty itself is constitutional. Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg joined Breyer's opinion. They stopped short of declaring their outright opposition to capital punishment.

"I believe it highly likely that the death penalty violates the Eighth Amendment," Breyer said, drawing on cases he has reviewed in more than 20 years on the Supreme Court bench.

More than 100 death row-inmates have been exonerated, showing that the death penalty is unreliable, Breyer said. He said it also is imposed arbitrarily, takes far too long to carry out and has been abandoned by most of the country. Last year, just seven states carried out executions, he said.

In 1972, the Supreme Court struck down every state's death penalty laws. Some justices believed at the time that this decision effectively would end capital punishment.

Instead, many states wrote new laws, and four years later the court reinstated the death penalty.

In an extremely unusual turn Monday, four justices read their opinions from the bench in the lethal execution case.

Justice Antonin Scalia, part of the court's majority, complained that the liberal justices were willing to discard long-settled principles in a term in which the left side of the court won most of the closely contested cases, though not the lethal injection dispute.

The Supreme Court's involvement in the case began in January with an unusually public disagreement among the justices over executions. As the case involving the pending executions of three Oklahoma death-row inmates was being heard, Justice Samuel Alito said death penalty opponents are waging a "guerrilla war" against executions by working to limit the supply of more effective drugs. On the other side, liberal Justice Elena Kagan contended that the way states carry out most executions amounts to having prisoners "burned alive from the inside."

In 2008, the court upheld Kentucky's use of a three-drug execution method that employed a barbiturate as the first drug, intended to render an inmate unconscious. But because of problems obtaining drugs, no state uses the precise combination at issue in that case.

Last April's execution of Clayton Lockett was the first time Oklahoma used midazolam. Lockett writhed on a gurney, moaned and clenched his teeth for several minutes before prison officials tried to halt the process. Lockett died after 43 minutes.

Executions in Arizona and Ohio that used midazolam also went on longer than expected as inmates gasped and made other noises before dying.

Meanwhile, the court challenge has prompted Oklahoma to approve nitrogen gas as an alternative death penalty method if lethal injections aren't possible, either because of a court ruling or a drug shortage.

In response to Monday's decision, Oklahoma Gov. Mary Fallin said she expects state courts to set new execution dates for the three inmates involved in the case. Oklahoma Department of Corrections spokeswoman Terri Watkins said the state has the necessary drugs for carrying out the executions.

Associated Press writers Jessica Gresko and Sam Hananel in Washington and Sean Murphy in Oklahoma City contributed.