Canada’s current disjointed approach to vaccinating children against hepatitis B makes no sense, says one hepatitis expert who would like to see all babies vaccinated against the virus at birth.

The World Health Organization recommends that all infants be vaccinated against the liver disease as soon as they are born.

But in Canada, each province has a different vaccination schedule when it comes to hep B, and that puts young children at risk of contracting the dangerous virus, says Dr. Harry Janssen, the director of the Toronto Centre for Liver Disease at Toronto General Hospital.

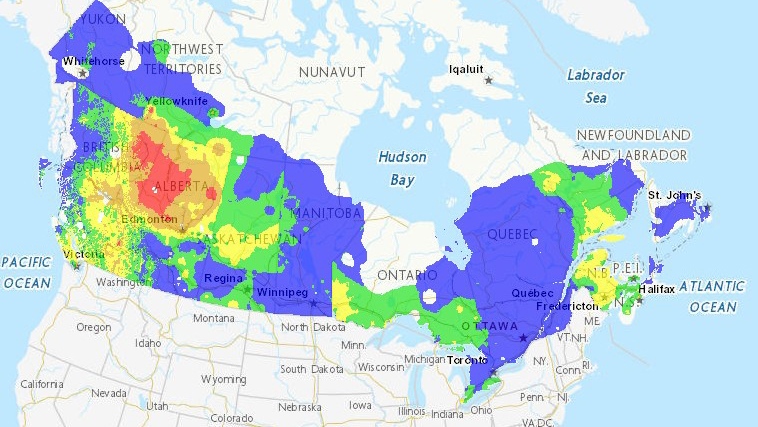

Currently, only New Brunswick, Nunavut, and the Northwest Territories offer the first dose of the vaccine at birth. Yukon, Quebec, British Columbia, and Prince Edward Island, vaccinate children at age two months.

But Ontario and Nova Scotia wait until children are 12 years old before offering the vaccine. Manitoba vaccinates at age 9, Alberta at age 10, while Saskatchewan and Newfoundland and Labrador wait until age 11.

Dr. Janssen says infant vaccination is already commonplace in most developed countries and even many developing countries. In fact, the World Health Organization recommends that infants receive their first within 24 hours of birth.

Janssen, who is presenting this week at the Global Hepatitis Summit in Toronto, says it’s critically important to vaccinate children at birth to ensure they don’t develop the chronic liver diseases the hepatitis B virus can cause.

The virus is highly contagious and is transmitted through contact with infected blood or body fluids. It can be spread by through unprotected sex, shared needles, or even by sharing contaminated personal care articles such as razors, nail clippers or toothbrushes.

“There is a misconception that we only need to offer older children vaccination in the years before they become sexually active, since sexual activity is one of the routes of transmission,” Janssen said in a statement.

“However, all babies and young children face other risks of blood to blood transmission from the moment they are born. This can happen through household contacts, at school playing together with other children and in many other places.”

A many as 95 per cent of adults who are infected with hep B will be clear of the virus within six months. But when infants and young children contract the illness, more than 90 per cent go on to develop chronic infection, which can progress to cirrhosis, liver cancer, and death if left untreated.

The risk of this progression is highest when infants are infected, while as many as 50 per cent of children between under the age of five can develop chronic infection.

Janssen says moving to infant vaccination in Canada instead of having different vaccination policies across the provinces could help to slash the number of new infections in children to nearly zero.

“Since all children across Canada will eventually be vaccinated regardless of where they live, why don’t we just remove this lottery and routinely vaccinate them all from birth?” he said. “This is the best way to ensure that they are all vaccinated and none slip through the system.”

It’s estimated that 230,000 Canadians are currently infected with hepatitis B, although only 58 per cent of them are aware of their infection.