The number of people of average weight is on the decline in low- and middle-income countries, says a new joint Canadian-U.S. study -- a trend that researchers warn will make it increasingly difficult to set health-care policy as populations settle into two diverse categories: the overweight and obese, and the undernourished and underweight.

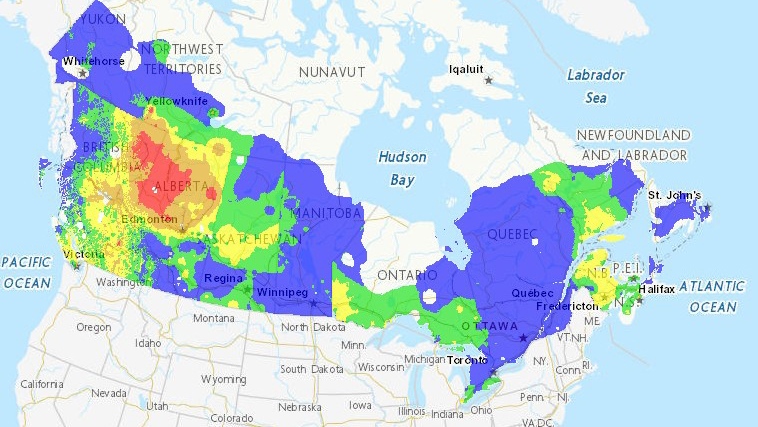

Researchers from the University of Toronto and the Harvard School of Public Health gathered data from 37 countries and found that while overweight and obese segments of the population were experiencing rapid weight gains, the same could not be said for those who were underweight.

For their study, the researchers used data from the Demographic and Health Surveys, a U.S. project that monitors health and population trends in developing countries. They looked specifically at the body mass index (BMI) of 730,000 women between 1991 and 2008.

The researchers found that, where average BMI among a population increased, the number of overweight and obese women increased far more rapidly than did the decline in the number of underweight women.

BMI is a measure of body fat, calculated by dividing weight in kilograms by height in metres squared, which health professionals use to determine whether someone is underweight, normal weight, overweight or obese.

The researchers found that for every 1.0 kg/m2 increase in mean BMI, there was a 60 per cent greater increase in overweight and a 40 per cent greater increase in obesity than the decline in underweight.

Lead researcher Fahad Razak, a fellow in internal medicine at the University of Toronto who also works at St. Michael’s Hospital, said that ideally, a population has “as many people as possible” in the average weight category.

However, the findings show that “that group is disappearing,” he said.

“We’re getting less and less of the average-weight people in these populations,” Razak told CTVNews.ca in a telephone interview. “You’re getting a persistent problem with the severely underweight and at the same time at the other end, you’re getting a lot more people who are really overweight.”

The findings are published in the journal PLOS Medicine.

According to Razak, who is also a research fellow at the Harvard School of Public Health, the problem of a large segment of the population being underweight or undernourished is unique to low-income countries, where wealth and higher incomes are linked to obesity and where lower-income residents struggle to find food.

In Bangladesh, for example, between 25 and 30 per cent of the population is severely underweight, and the percentage of people that are underweight is ten times higher than those who are overweight or obese. In such low-income countries, Razak said, this segment of the population “doesn’t have the basic ability to get enough calories for day-to-day existence.”

In wealthier countries, meanwhile, lower-income residents have access to a variety of cheaper foods, which are often more calorie-dense, which has led to a rise in obesity among this population.

Ideally, Razak said, from a health perspective, the majority of the population would be somewhere in the average weight range.

“How you are going to treat an obese, largely wealthy population is very different than how you’re treating a poor, malnourished population,” Razak said. “And they’re existing in the same countries with one healthcare system. So they’re having these very big demands from these two very different populations.”

According to the study, people who are underweight are at an increased risk of death due to complications that can arise from being malnourished. Being overweight or obese is linked to an increased risk for a myriad of health problems, from heart disease to diabetes.

Health policy aimed at treating an overweight and obese population -- diet and exercise, for example -- is very different from the approach needed for an underweight and undernourished population.

“With malnourished populations, it’s not that you have a specific health intervention that’s going to help them,” Razak said. “It’s really about economic development and ensuring that they have adequate nutrition. It’s a different kind of intervention that’s required.”

Razak said the research team is now focused on determining whether similar patterns can be observed in high-income countries, with a special focus on the United States.

They will also look at how much disease prevalence and mortality rates can be blamed on the lack of weight gain among the underweight and the excess weight again among the obese.