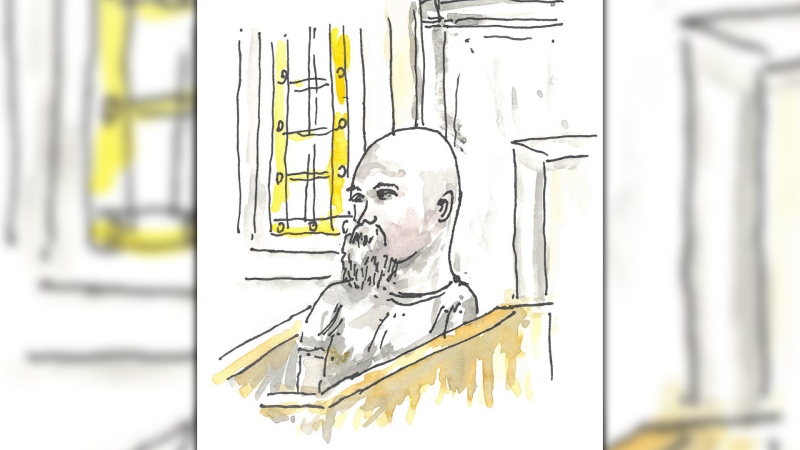

TEGUCIGALPA, Honduras - A surveillance camera captured it all: Rigoberto Paredes shoved the lawyer into an elevator and stabbed him 10 times with a small knife before he slit Eduardo Montes' throat. The assailant tried to escape down a stairwell, but was caught by security guards.

"Nobody told me to do this - this was for the people. The people deserved this," Paredes declared in a taped confession.

The murder video was widely circulated, but rather than condemn the brutality, many Hondurans defended Paredes as a national hero for standing up to corruption. Some went so far as to say that a country sickened by theft and scandal was the real cause of the death.

Paredes justified the killing by saying Montes had defended politicians accused of embezzling money from the country's social security system in which an estimated $400 million assigned for hospitals and medications simply disappeared. And Montes aspired to a seat on the Supreme Court.

For months, tens of thousands of Hondurans have taken to the streets to demonstrate against official corruption, and especially the social security scandal, which has left thousands of people without access to medical care in a country with an already limited health care. While the government has not released any information on how many people may have died as a result, protesters claim thousands have lost their lives due to a lack of access to dialysis treatment, chemotherapy and myriad other medications for acute and chronic ailments.

The scandal has tainted congressmen, businessmen, Cabinet members, government officials and even the president, Juan Orlando Hernandez, who admitted in a televised interview that part of the diverted money, $120,000, had been used for his election campaign. He promised to return it.

The course of the investigation into the embezzlement has mirrored the country's handling of so many other crimes: Three witnesses were killed, others have been threatened, and some linked to the scandal have been forced to flee Honduras for their own safety.

By September, when Montes, 44, was stabbed to death in the elevator, the public's disgust with politicians had reached a fever pitch.

"He should be freed, this brother did what any justice-loving person would do," said one comment on the website of a newspaper that posted the security video. "We were not born to suffer injustice, we were born to turn injustice into justice," another said. A Facebook page called "Rigoberto Paredes, National Hero" attracted 2,300 members in less than 48 hours.

Fabricio Estrada, poet, political activist and one of Paredes' oldest friends, described the 28-year-old graphic designer as having a "cause" in a country that is itself "terminally ill."

"It makes you sick in the head," Estrada said. "It is the country that kills, not the person. Nobody thought that Rigoberto could commit a crime."

In a Facebook post, Paredes' mother wrote: "You have done the most incisive and profound reading of the events around you. You have looked beyond to what others do not see. I know that if you were not living in a country like ours, you would not be in the situation in which you find yourself."

But Rafael Canales, the vice-president of Honduras' bar association said: "What happened is unfair. It is unfair to attack a lawyer for defending this person or that person. Defending someone who is on trial is a constitutional right. It is what lawyers do. Being a lawyer in Honduras is a frightening, high-risk experience."

Honduras, a Central American country of 8 million people, has long teetered on the brink of national collapse. It has one of the highest homicide rates in the world. More than 90 per cent of criminal cases are never solved. Competing gangs terrorize the populace, with thousands of people paying extortion fees merely to run fruit stands, drive taxis and operate small stores. Even renters and homeowners must pay the fees or face death.

The rampant violence, fueled by the cocaine trade from South America to the U.S., has led to a wholesale exodus, with tens of thousands of people abandoning their homes each year in hope of a better life up north.

An engrained feeling of helplessness and frustration over the health care scandal "undoubtedly affected" Paredes' behaviour, said Arabeska Sanchez, a top Honduras crime expert. Under those circumstances he "looks like a hero and part of society believes that," she said.

"There's a clear link between what is going on in the country and this crime," Sanchez said.

She noted that despite a supposed investigation into the missing millions, "there has not been a single sentence against a single politician, a powerful family or businessman, even though for months the media has published details of the corruption scandals."

To date, some two dozen people have been detained, including the director of the country's social security agency, two deputy ministers and several businessmen.

Montes, the slain lawyer, represented Lena Gutierrez, the vice-president of Congress, as well as two of her siblings and her father. All four are charged with selling overpriced and inferior medications to the Social Security Institute, which manages public health care. They remain under house arrest after posting $4 million bail. Like others facing charges in the scandal, Gutierrez has not resigned, and their trials have not yet been scheduled.

Montes also represented Rigoberto Cuellar, a deputy attorney general who is being investigated over allegations that he accepted bribes in an attempt to derail the probe.

Many Hondurans don't believe the nation's justice system can handle the inquiry and are demanding that an international, independent commission be named along the lines of the one in neighbouring Guatemala. There, the commission investigating a corruption scandal resulted in the imprisonment of many government officials, including former President Otto Perez Molina.

Hondurans' skepticism is not unfounded: In addition to the attacks on witnesses, the prosecutor who began the inquiry was forced to leave the country last April along with his family after the government told him it could not guarantee his safety. Most suspects are being held on a military base instead of prison due to similar concerns.

The health care scandal began making headlines at the end of 2013 amid reports that the Social Security Institute had paid almost $1 million for 10 ambulances that were not much more than repainted vans. The head of the government agency, Mario Zelaya, fled the country but was captured in Nicaragua.

A group called the Association for a More Just Society began looking into suspicious purchases of medications in 2007 and handed a report to the attorney general's office as 2013 drew to a close.

Carlos Hernandez, president of the Association for a More Just Society, said his group's research found that the health care scheme was not much different than those used by drug cartels. The research concluded that three big business chains owned 15 to 20 companies that control Honduras' medication supply. The amount of money embezzled over four years, nearly $400 million, equals roughly a tenth of the government's annual budget.

According to the association, those who controlled pharmaceuticals meant for the public frequently stole drugs and resold them to private pharmacies, and some doctors took the drugs to private hospitals and sold them to patients at inflated prices. Others hid or buried medications so they could justify further purchases.

"The purchase documents are perfectly fine, with the required signatures and stamps, but the drugs never made it to the health ministry's storage facilities," Hernandez said.

In some cases, bottles of medication were empty or contained pills with no active ingredients. Some were expired. Sometimes, thieves were hired to steal drugs from drivers en route from the storage facility to a hospital, in order to resell them later, the association found. For that reason, drug deliveries now are handled by the military.

In one case in Comayagua, north of Tegucigalpa, one hospital's management purchased $1.5 million in medications that were never delivered, even though Hernandez said the purchase order was signed by 110 different officials.

German Leitzelar, a former minister who was part of a local commission investigating the issue in January 2014, said that hospitals had only 20 per cent of the medications necessary to function when his panel began its work and that some medications had been jacked up as much as five times their original price.

Hernandez said the association had to give the public prosecutor's office computer disks to store evidence because the authorities lacked the necessary equipment to handle such a large amount of information.

"They don't have enough prosecutors. They don't have adequate training. The same prosecutor who is investigating a cellphone theft has to be in charge of a case like this one," he said. "If the justice system doesn't even have the capacity to store the information on a computer drive in a case like this, imagine what they would need to investigate corruption in all levels of government."

Many of those who have joined protests hold little hope that much will change, like Gloria Cabrera, who regularly marches to mourn the death of her son, Felix Cruz, who suffered from birth defects related to malpractice when doctors failed to treat him for an incompatibility with his mother's blood.

Cabrera won a court settlement requiring the social security agency to care for her son, but the government got the ruling reversed, with a judge decreeing that the boy's medical costs caused "great harm" to the social security system.

"My mother's heart cries out for justice," Cabrera's protest banner reads. She wrote the words in her own blood.