A registered nurse recently posted an unusual X-ray to Figure 1, an image-sharing network sometimes referred to as the Instagram of the medical world.

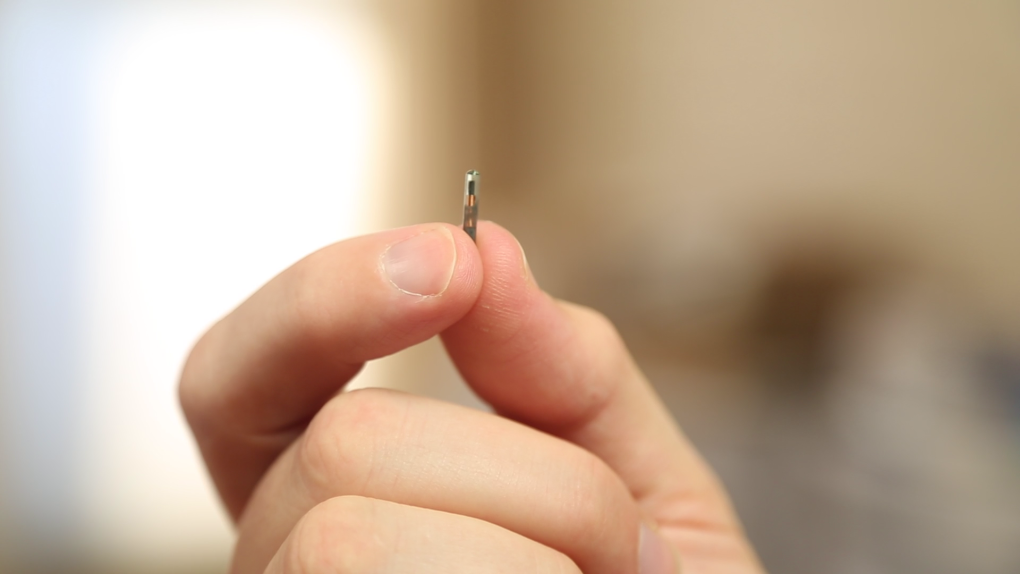

The image struck the nurse because of a curious, tube-shaped object implanted in the webbing between the man’s fingers. When the nurse asked about it, the patient replied that it was a chip that allowed him to “wave his hand to pay for things.”

While the patient sought medical attention for an unrelated issue, the curious little chip piqued the nurse’s interest. So the nurse shared the X-ray online.

“He says he's planning to insert a few other devices so that he can open his garage door, etc.,” the nurse later wrote in a comment on the photo. “I told him I do all of that from my phone, without the risk of infection, and with the ability to update as needed. Pffff, strange cat this one is.”

Strange as it may seem, the practice of implanting tiny chips inside the hand to unlock doors, phones or even a computers isn’t entirely uncommon.

Supporters call this biohacking, and estimates suggest that thousands of people around the world have similar radio frequency identification (RFID) implants in their hands.

But some doctors aren’t convinced it’s a great idea.

“These are always do-it-yourself jobs, and typically health care professionals aren’t physically involved with the implantation of these devices,” said Toronto-based physician Dr. Josh Landy, who is also co-founder and chief medical officer at Figure 1.

“Obviously as a health care professional I couldn’t possibly advise somebody that the convenience is worth the risk of infection or damaged tissue.”

Figure 1 shared the story behind the strange X-ray last week in a Medium post titled “Part man, part wallet.” The platform, used by an estimated one million medical professionals, was looking to highlight the phenomenon, which Landy says health care providers see “from time to time.”

What is biohacking?

Followers of the biohacking movement, which emerged around the mid-2000s, believe that technology can be harnessed to enhance the human body. Some say these implants could provide new technology-based capabilities and render wallets and keys obsolete. Some even suggest that biohacking could offer a technological leap forward in human evolution.

In a broader sense, the term “biohacking” has been used to describe non-traditional research by scientists who tinker with biology, often in the realm of genetics, or people who use non-intrusive means to alter their bodies, such as applying electricity to the muscles or brain for a certain desired outcome.

Anywhere from 10,000 to 20,000 people across the globe are estimated to have the RFID implants in their hands, according to Amal Graafstra, who owns a U.S. company that sells the chips.

“Really, the question is why wouldn’t you do this?” Graafstra told CTVNews.ca. “It’s kind of a no-brainer when you think of what the potential is.”

Graafstra has referred to himself as a “pioneer of the DIY RFID implantation movement,” and with good reason. He’s had a chip in his left hand for over 11 years, has written a book about the uses of implant technology and has personally performed implants on an estimated 800 people.

How does it work?

The battery-free technology is primarily used for identification purposes. For instance, users could program a receiver on their front door to read their unique chip with the wave of a hand. The chip can similarly be linked to security features on personal technology, such as a computer hard drive or cell phone.

Graafstra’s company, Dangerous Things, has partnered with body piercers across the world to provide a sterile environment to get the implants. He compares the level of risk involved to having an ear pierced.

As for future possibilities, Dangerous Things is in the midst of developing a platform that would allow users to upload an array of applications onto the chip, such as a local transit pass, a Bitcoin wallet or a variety of personal keys.

“You can imagine a future where somebody goes into a bank, opens an account, accesses it online, transfers money at an ATM but never having to put a PIN or using a password because they’re proving their identity through this system in a very strong cryptographic way,” Graafstra said.

“The same thing (could be done) with Facebook, with messengers, with any kind of transaction.”

But what happens when technology evolves? Graafstra says that while advances are inevitable, the way people use technology is grounded in personal choice. For instance, a person can surf the internet on a state-of-the-art laptop or a desktop they purchased in 2009.

“Still today, I can go on eBay and buy a brand-stinkin’ new (chip) reader for $10 that will read it,” he said, referring to the RFID chip in his left hand. “The idea of obsolescence is more of a choice then necessity.”

Changing times

When Graafstra first began selling RFID chip implants about three years ago, he said his customers often fit a certain profile: they were already deeply familiar with the technology.

“Now today, it’s a mix. We definitely have people who come to our site and come to events and see what we’re doing and say, ‘Wow, that’s interesting, what can I do with it?’” he said. “So they’re not aware of the technology in a technical or intimate sense, but they are intrigued by the possibilities.”

Graafstra admits that biohacking isn’t for everyone.

“I totally accept that. I’m not expecting everyone in the world to run out and get one,” he said.

But Graafstra stands by the belief that the implants are more than a passing novelty.

“I’m sure there are a lot of critical technologies that we have today that were just thought of as novelties. It just takes time. Over the last decade I’ve had various types of media coverage, and even the media coverage is changing. Originally it was, ‘Why are you such a freak?’ Now it’s like, ‘Oh, this is very interesting.’”

Medicine vs. convenience

Back at the doctor’s office, Landy points out that technologies similar to the RFID chip have become part of many doctors’ 21st century “tool kit.” For instance, cardiologists can now use tiny implants placed near a patient’s heart to detect heartbeat abnormalities and relay them back to a doctor using radio frequencies.

“So these things exist both for convenience and for what I’ll call conventional medical application,” Landy said. “And I’m sure the berth between those things is going to be growing smaller as time goes by.”

Still, Landy insisted that getting a non-medical implant outside a medical environment “does not strike me as a safe idea.”