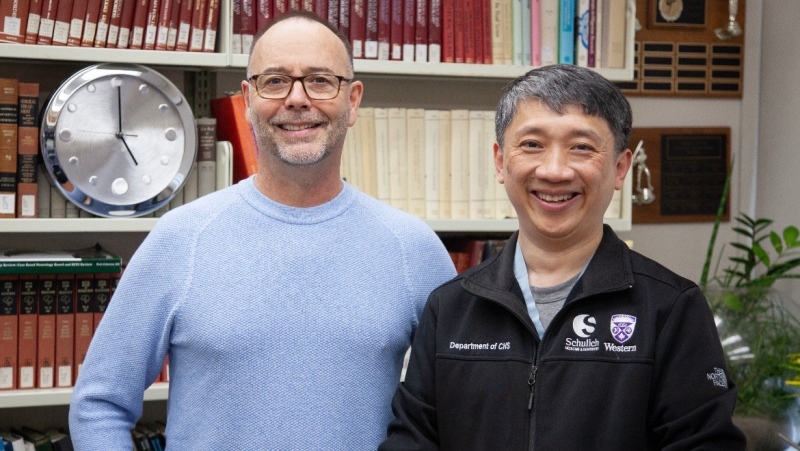

Canadian researchers say they’ve shed new light on a “genetic basis” for higher blood pressure in women -- something that could help identify which women are at greater risk for heart disease later in life.

A study out of Western University -- published online this week in the British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology -- points to a variation in the estrogen receptor GPER.

When functioning normally, GPER relaxes blood vessels, lowering blood pressure.

But a common genetic variant of GPER -- P16L GPER -- makes the receptor less active, which can drive up blood pressure and lead to hypertension.

The gene variant is found in about 20 per cent of the overall population. But researchers found only female carriers of this variant -- not male -- have higher blood pressure.

“This is one step in understanding the effects of estrogen on heart disease, and understanding why some women are more prone to heart attack and stroke than others,” lead researcher Ross Feldman said in a statement.

According to the Heart and Stroke Foundation, high blood pressure is the single biggest risk factor for stroke and a major factor in developing heart disease.

To reach their conclusions, the team studied two groups: 507 “healthy” subjects and 150 patients currently being treated for high blood pressure.

The subjects went through a series of blood pressure and heart rate tests, while also having a blood sample taken to test for genetics.

The researchers found:

-

Systolic blood pressure was “significantly higher” for individuals with the P16L GPER variant in the “healthy” group – but only in female subjects.

-

Twice as many women with high blood pressure (31%) had the variant, compared to men with the condition (16%).

- One-third of women with high blood pressure (31%) had the variant, compared to only 23 per cent of “healthy” females.

The mean age of women in the “healthy” group was 24, compared to 54 for women already being treated for high blood pressure.

Women tend to develop high blood pressure after undergoing menopause. But while the research does point to a possible explanation for this sex-specific phenomenon, awareness of the health risks is as important as pinpointing their cause, said cardiologist Beth Abramson.

“Even with very exciting research like this that does point to a genetic difference between women and men, we have good treatments available for women,” said Abramson, who works at St. Michael’s Hospital in Toronto.

“Women need to know their risk and reduce their risk as we’re working on cutting-edge treatments down the road.”

Feldman, also a clinical pharmacologist at London Health Sciences Centre, said heart disease is often thought of as a “men’s only” disease.

But he noted that post-menopausal women are just as likely as men to develop heart disease, and are less likely to be properly diagnosed and treated because of these misconceptions.

“We used to think that women lived longer than men; heart disease wasn’t a problem. We know that’s not true,” Feldman said.

The GPER variant can be detected using standard diagnosis techniques. And Feldman says these findings could be used to shed light on the differences between hypertension in men and women, leading to more effective treatments based on sex.

“Our work is a step forward in developing approaches to treating heart disease in this underappreciated group of patients,” he said.

“I think we’re starting to open the door on the genetics of heart disease.”