Leilani Schweitzer's 20-month-old son, Gabriel, died because of two hospital errors.

The first came when a hospital in Reno, Nev. misdiagnosed Gabriel's chronic brain condition as a stomach flu.

The second came days later at Stanford University Hospital, when a nurse switched off baby Gabriel's heart monitor alarms so Schweitzer could sleep.

Gabriel's heart stopped, and he died.

Now, nine years later, Schweitzer works at the hospital where her son died as an advocate for better hospital-patient communication. She says medical mistakes – even fatal ones – are hard to totally avoid, but hospitals can control how patients and families are treated after a mistake is made.

"Those are choices. Those are deliberate things that hospitals can do to help patients and their families afterward," Schweitzer told CTV's Canada AM on Thursday. Schweitzer spoke to CTV News from Vancouver, where she was slated to speak at a conference on patient and family healthcare.

Schweitzer said Stanford Hospital did not deny nor defend the disastrous mistake that led to her son's death. Instead, hospital officials were upfront and honest about it. Schweitzer said that honesty helped her work through her grief, and also kept her from filing a lawsuit. "Instead of shutting me down, not answering my questions, they created a collaborative relationship with me," she said. "They investigated, they found the weakness in the monitoring system, and they made improvements to make all of the children at the hospital safer."

The hospital determined Schweitzer's son Gabriel died after a nurse unwittingly silenced his medical alarms so his mother could sleep. The alarms kept going off whenever the baby moved, and Schweitzer was trying to sleep in the same room as her ailing child. "I thanked her," Schweitzer said. "The nurse – she saw how exhausted and tired I was."

The nurse had meant to silence only one alarm, but she unwittingly disabled all nine monitors attached to the toddler. When Gabriel's heart stopped beating, no one noticed until it was too late.

Schweitzer said hospital staff recognized her need to make meaning from her son's tragic death, so they offered her a job as Stanford's first patient liaison. "I work with them every day to help people who have had similar experiences," she said. "No one wants these things to happen."

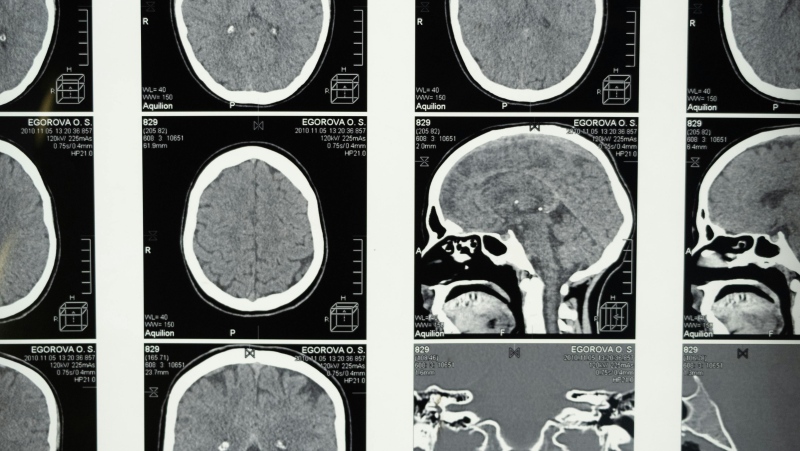

Schweitzer's son Gabriel suffered from hydrocephalus. The condition – commonly known as "water on the brain" – occurs when spinal fluid does not fully drain from the brain. Doctors implanted Gabriel with a shunt to drain the spinal fluid, but the shunt was prone to failure and occasionally needed to be changed. A complication with the shunt ultimately contributed to Gabriel's death.

Since Gabriel's death, Schweitzer has become an outspoken advocate for better hospital-patient communication. She delivered a speech on the subject for a TEDx video shot at the University of Nevada this year, and is scheduled to speak in Vancouver this week at the International Conference on Patient- and Family-Centred Care.