Thousands of lifesaving heart bypass surgeries are performed in Canada every year, but now many former patients are being informed they may have been exposed to a serious bacterial infection.

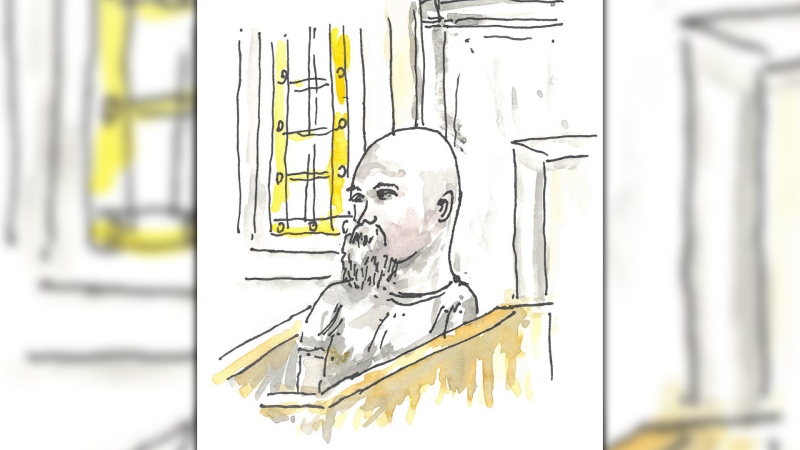

Toronto-area resident Chris Clough received a letter this week from the hospital where he had a quadruple bypass in 2012, warning him about “a potential infection risk related to their surgery.”

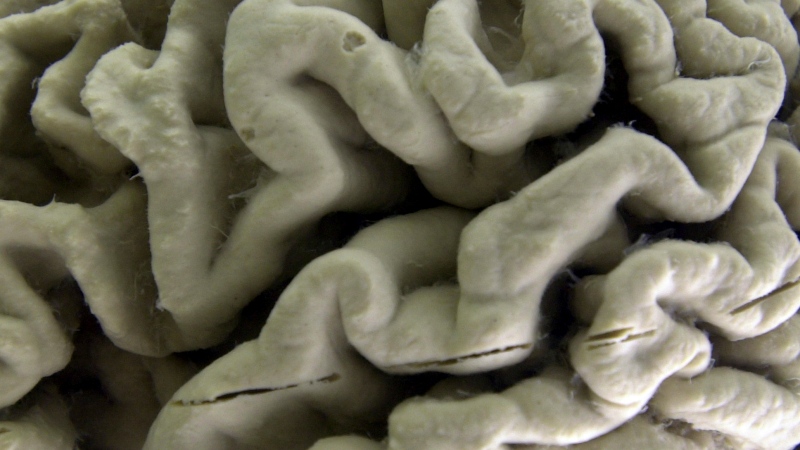

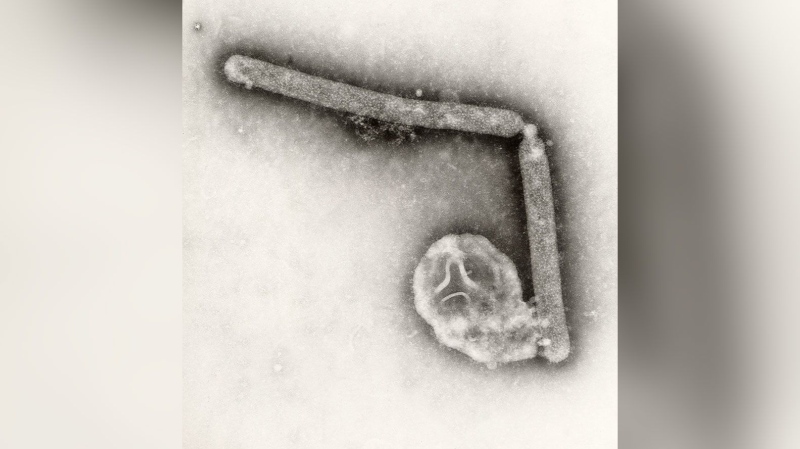

The letter told him that a device used to heat and cool his blood during the surgery has been linked to a rare bacterium called “mycobacterium chimera,” or M. chimera, which can cause potentially fatal infections.

Clough says he’s worried because although it’s been five years since his surgery, the letter informed him that the symptoms can take months or even years to appear.

“There are symptoms there in the letter that I've been complaining about for years. Muscle ache, fatigue, pain in my right side,” he told CTV Toronto.

He’s also worried because his latest blood tests have shown an alarmingly high white blood cell count, suggesting an infection of some kind.

“I'm praying to God that I don't have this infection,” he said.

Earlier this week, Alberta Health Services confirmed that an open heart surgery patient there had been diagnosed with a M. chimera infection. The patient, who had received heart surgery about a year before developing symptoms, received treatment but ultimately had to have more heart surgery.

Two other diagnoses have been made in Quebec.

Last fall, Health Canada and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control issued public warnings about the potential risk of infection in patients who had had heart surgeries since 2012.

Those warnings came after the agencies learned that some heater-cooler units manufactured by LivaNova PLC may have been contaminated with bacteria.

Heater-cooler units are used during heart procedures to help control a patient’s body temperature. The CDC says approximately 60 per cent of heart bypass procedures in the U.S. use the devices linked to these infections.

The devices contain water that is heated or cooled depending on the patient’s needs. But the water can harbour bacteria, which can then be released into the air through the unit’s exhaust vent.

Once the bacteria enter a patient’s body, they grow slowly and undetectably, often not causing symptoms for months.

The CDC estimates the risk of infection to be less than one per cent. But for those infected, the treatment is extensive, requiring taking antibiotics for more than a year.

At least 100 heart patients worldwide have been identified with M. chimaera infections after cardiac surgery, mostly in patients whose surgery were lengthy and included implants such as heart valves.

Clough is now one of hundreds of Canadian heart surgery patients receiving warning letters from the hospitals where they had their surgeries.

The letters advise patients that if they have noticed worsening health or symptoms of an infection, they should contact their cardiac healthcare provider or family physician.

Symptoms to watch for include fever, unexplained and persistent night sweats, unintentional weight loss, muscle aches, fatigue, as well as redness or pus along their surgical incision.

With a report from CTV Toronto’s Tracy Tong