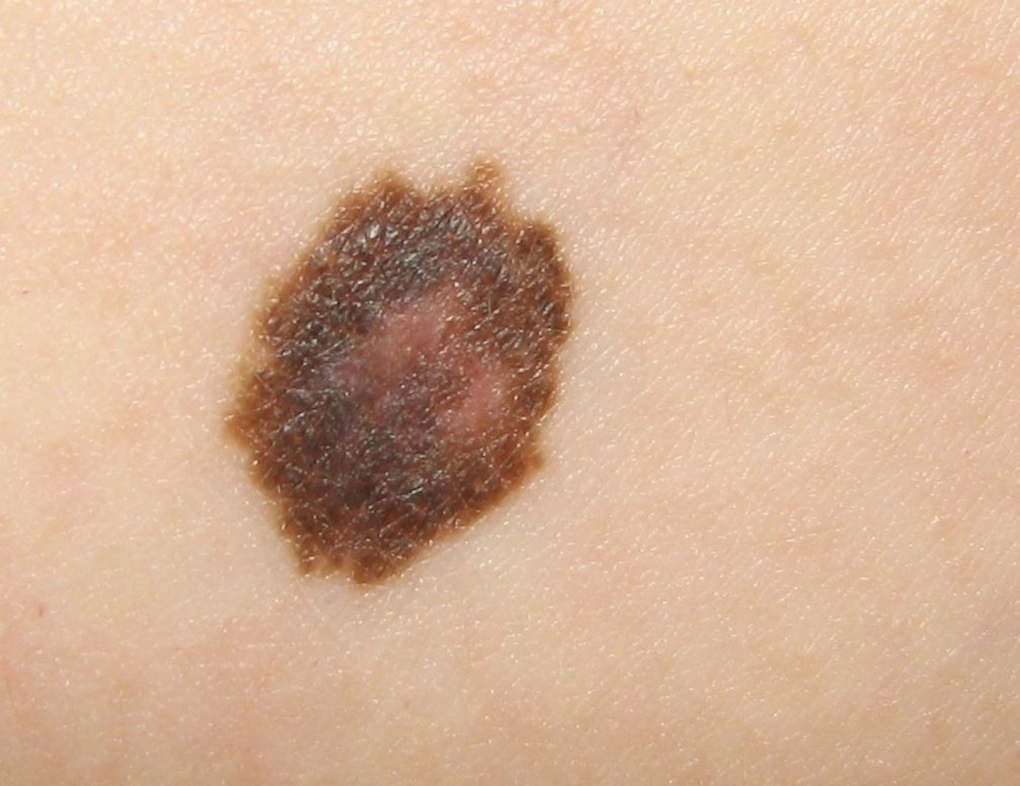

TORONTO -- Smartphone apps that analyze photos of moles to assess whether they might be potentially deadly melanoma or benign lesions vary widely in accuracy, say researchers, who warn patients against using them for diagnosis.

A study of four such applications, available free or for a modest cost from the two most popular online app retailers, found they incorrectly classified at least 30 per cent of melanomas as being of no concern.

"One of them was so bad that it actually missed over 93 per cent (of the melanomas)," said principal author Dr. Laura Ferris, a dermatologist at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center.

"That's kind of scary."

Melanoma, the most serious type of skin cancer, can develop in an existing mole or arise as a fresh pigmented or unusual-looking growth on the skin. They can develop anywhere, but are most common in areas previously exposed to sunlight, such as the back, legs, arms and face. However, melanomas can also appear on the palms of the hands and soles of the feet.

If caught early when it is confined primarily to the skin's surface and treated, this skin cancer has a high cure rate. But the survival rate for patients whose melanomas have gone undetected and spread to other areas of the body can be dismal in some cases.

"The prognosis associated with melanoma is highly dependent on when it's detected and removed," Ferris said from Pittsburgh. "If melanoma becomes deeper and deeper, your survival is lower and lower."

So if an app mistakes a melanoma for a benign lesion, a patient may feel reassured and wait to consult a doctor for several months, giving the melanoma time to further invade tissues underlying the skin.

"That can be a problem because that melanoma is getting deeper and it's able to metastasize," she said.

To conduct the study, published Wednesday in JAMA Dermatology, the researchers submitted 188 photos of lesions to each of the four smartphone apps, none of which was identified by the authors.

The researchers knew the status of the moles or lesions -- 60 were melanomas and 128 benign -- because they had been photographed before being removed or biopsied and sent to an in-house pathologist for testing.

"We knew what they were, either cancer or not," Ferris said. "And we went with the two ends of the spectrum: it's frankly melanoma or it is a really low-grade, not bad pigmented skin lesion."

The researchers wanted to see whether assessments by the four apps matched the previously confirmed diagnoses.

Ferris said three of the apps give answers within a minute after a photo is uploaded. The fourth, which forwards the photo to a U.S. board-certified dermatologist for analysis, takes about 24 hours to provide an online opinion as to whether a lesion is suspicious or not.

"And the main thing we were looking at was how often did they get melanoma right or how often did they miss it," she said.

"Interestingly, the results we got from the one where you had a dermatologist just looking at the picture ... was actually very good. It was 98.1 per cent.

"So there was a big difference between the performance of the dermatologist versus these (other three) applications."

Dr. Cheryl Rosen, a dermatologist and researcher at the University Health Network in Toronto, agrees with the authors' concern that people might use an app as a substitute for seeing a doctor about a suspicious mole or lesion.

For one thing, a photo could be blurry or of poor quality, said Rosen, noting that dermatologists use special equipment and lighting to assess a mole or skin lesion before deciding whether a biopsy is needed to confirm a diagnosis of cancer.

"My concern is that somebody will be told that it's nothing to worry about and I think that would be doing them a disservice when they need to really have their pigmented lesion ... evaluated by a physician or dermatologist."

Dr. Michael Sabel, an oncologist who specializes in melanoma, said this was a key issue when he and colleagues at the University of Michigan designed UMSkinCheck, an app designed for patients to keep track of changes in moles and skin lesions over time.

The app, available free through iTunes, asks users to input 23 photographs of various parts of the body. Within a set period of time -- perhaps every couple of months -- the app sends a reminder to take a new set of photos so the images can be compared side by side.

"When we originally started designing it, one of the things that people had suggested was should we have the option for people to send the photographs to us in order to make a diagnosis," Sabel said Wednesday from Ann Arbor, Mich.

"And we decided against it."

While it's a good idea to take advantage of mobile technology to give people the tools that allow them to be at least partially responsible for their own health care, "we're not at the point where we can substitute the app for doctors and other health-care professionals," he said

"This should be a tool to be used in concert."

Ferris said the overall performance of the apps in picking up melanomas was unacceptable.

"Some of the lesions we had looked pretty awful ... but the apps that we tested were telling us 'that looks good' or 'benign' or 'low risk,"' she said.

Currently there are no government regulations covering online health apps. "You can put whatever you want in an app store and sell it to people," she said, adding that there are more than 13,000 health-related apps available, which generated $718 million in revenue in 2011.

"And so the concern is that these are out there and they are available to the public and you can get this answer (about melanoma) with no doctor involved," she said, adding that the apps have not been tested through a clinical trial nor do they meet any quality standard.

"Would I personally like to see some sort of regulation? Yes," she said.

"I'm afraid for the safety of my patients, that if they're using something like this and it's 30 per cent of the time going to tell them that their deadly cancer is fine, not to seek attention for it, I think that's a risk, a real public health risk."