Ten days after a Malaysia Airlines jet with 239 people on board vanished, new questions are being raised about the men at the controls.

Particular attention is being paid to the fact that the plane's pilot, Zaharie Ahmad Shah, reportedly had built a flight simulator in his home. Authorities have now seized that equipment.

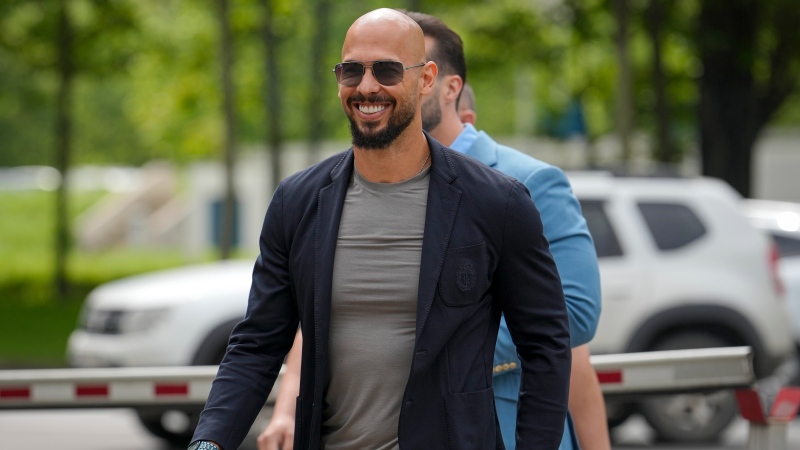

Aviation expert, Savik Ramkay, the coordinator of the aviation operations & safety program at Seneca College in Toronto, tells CTV's Canada AM that while some pilots might keep such simulators at home, "in this situation, it would have to raise some concerns."

He says investigators will now examine the machinery to try to determine whether it was used for fun or for something perhaps more sinister.

Anthony Brickhouse, an associate professor of aerospace safety at Embry-Riddle University in Florida, agrees the simulator is not unusual but bears examination.

"If you're in aviation, you probably have a lot of love for aviation and when you're not actively flying, you might want to be doing something that is connected to flying. So for a commercial pilot to have a simulator in his home is not something that would raise a flag," he told CTV News Channel from Daytona Beach.

"But… it's something you'd want to take a look into, to see if there were any odd manoeuvers the pilots would have been practising."

Also worrying is that Malaysian officials said over the weekend that it appears that two of the plane's key communication systems had been deliberately turned off before the plane turned sharply west onto a known flight route toward the Indian Ocean.

But officials backtracked from that position Monday.

Officials had previously said one of the jetliner's data communications systems called ACARS -- which relays information about the plane's performance -- had already been switched off by the time of the last communication between the flight crew and traffic controllers.

But Malaysian Airlines CEO Ahmad Jauhari Yahya said Monday that while the last data transmission from ACARS came before co-pilot Fariq Abdul Hamid calmly bid air traffic controllers, "All right, good night," it was still unclear at what point the system was switched off.

He said it's also possible that both ACARS and the plane's transponders went off later and at the same time.

“We don’t know when the ACARS system was switched off,” Ahmad told a news conference Monday evening.

Still, investigators have not ruled out the possibility that the plane was intentionally diverted, either by the pilots themselves or by someone else on board with aviation experience.

Ramkay notes that since the 9-11 attacks in which terrorists charged into the flight deck, changes have been made throughout the aviation industry to secure the door into the flight deck. In fact, it doesn't appear as if anyone has been able to breach a cockpit since those changes were made, Ramkay says.

"Post 9-11, we secured the flight deck door. But the question now is what happens behind that flight deck door now that it's secured," he said Monday.

It appears that whoever shut down these systems had "very, very specific knowledge" of how to do so, Ramkay says.

Questions are now being asked about the mental state of the pilots. Malaysian police say they are investigating the backgrounds of the pilots, as well as other flight and ground staff for any clues to a possible motive.

Ramkay says pilots undergo stringent psychological testing and interviews before they are hired for commercial airlines. The problem, he says, is that there is further testing once a pilot's career is underway.

"So how do you ensure that a pilot stays within the mental framework that you want for a pilot?" he wonders.

Incidents of pilots using their planes for suicide are very low. A 2014 .S. Federal Aviation Administration study found that in the U.S. at least, just 0.3 per cent of the 2,700 or so fatal aviation accidents has been caused by pilot suicide.

But that report also acknowledged that incidents of deliberate pilot sabotage "are most likely under-reported and under-recognized," That's because the topic of deliberate pilot sabotage appears to be a sensitive one among pilots, with investigators often wary to conclude a pilot purposely crashed a plane, even when most of the evidence suggests otherwise.

In 1999, the co-pilot of EgyptAir Flight 990 switched off the auto-pilot when he found himself alone on the flight deck, pointed the plane straight downward near the Massachusetts island of Nantucket, and calmly repeated the phrase "I rely on God" over and over. All 217 aboard died.

Yet the National Transportation Safety Board didn't use the word "suicide" in the 160-page report of the crash although it acknowledged the co-pilot’s actions were deliberate. Instead it said the reason for his actions "was not determined."

Egyptian officials rejected that report and the theory of suicide, insisting instead there was a mechanical reason for the crash.

There was also disagreement over the cause of the crash of SilkAir Flight 185, which plunged into a river in 1997 during a flight from Jakarta, Indonesia, to Singapore, killing all 104 aboard. A U.S. investigation found that the Boeing 737 had been deliberately crashed, but an Indonesian investigation was inconclusive.

Ramkay says that just as 9-11 changed security operations of the flight deck, this incident too will likely lead to changes because it's proven that it's possible to take a large commercial aircraft and simply make it disappear in the sky.

"This challenges both the civilian and military capability to manage and find a plane that has gone incognito, or stealth in a sense," he said.

With reports from The Associated Press