YANGON, Myanmar -- Myanmar voted Sunday in historic elections that will test whether popular mandate can loosen the military's longstanding grip on power, even if opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi's party secures a widely-expected victory.

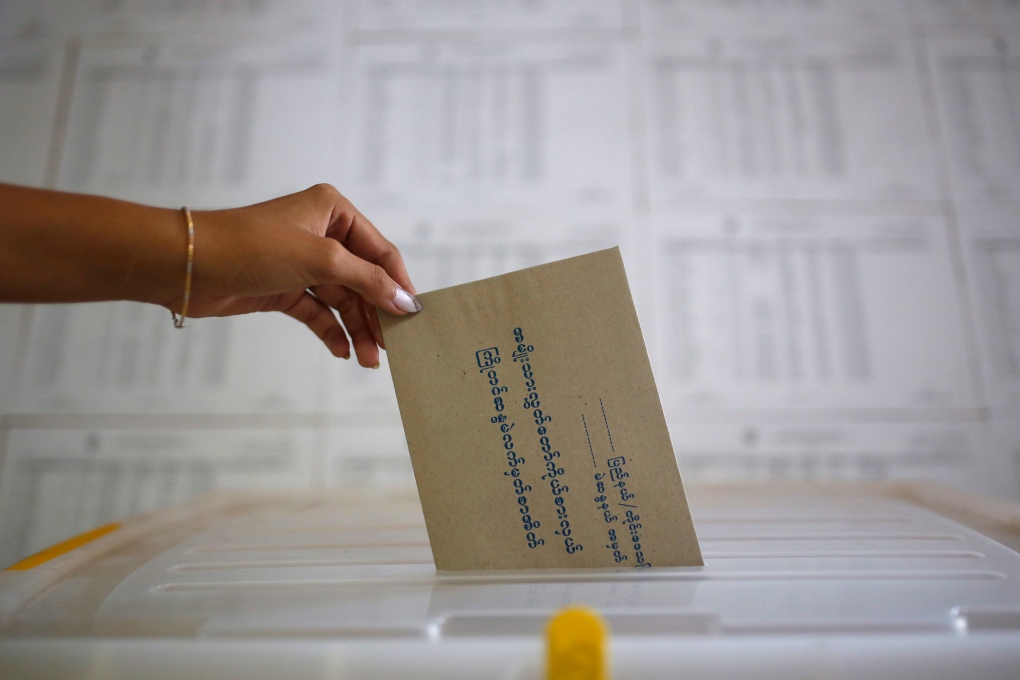

As voting opened at 6 a.m. (2330 GMT Saturday), lines began to form outside polling stations set up in Buddhist temples, schools and government buildings.

"I've am so excited to come to vote. I couldn't sleep the whole night, so I came here early," said Ohnmar, a 38 year-old woman who goes by one name. She was in a line at a polling centre in Yangon, where Suu Kyi will also vote.

"My whole family is excited. This is going to be my first experience," she said. "I came to vote because I want change in my country. I think Aung San Suu Kyi will win if this is a real free and fair election."

More than 90 parties are contesting, but the main fight is between the National League for Democracy, led by Nobel Peace laureate Suu Kyi, and the ruling Union Solidarity Development Party, made up largely of former junta members. A host of other parties from ethnic minorities, who form 40 per cent of the country's 52 million people, are also running.

Some 30 million people are eligible to vote.

"In general, these elections are important because they are the first real indicator of whether the democratic transition is going to take a big step forward or remain in a quasi-civilian middle ground for years to come," said Thant Myint-U, a historian and government adviser.

The election is seen as Myanmar's best chance in decades to move toward greater democracy if Suu Kyi's party secures the highest number of seats in the bicameral Parliament and gets the mandate to govern. But the NLD starts with a handicap: of the 664 seats in Parliament, 25 per cent are reserved for the military.

This means in theory the USDP, with the military's support, need not win an outright majority to control the legislature. To counter that scenario, the NLD would require a huge win.

That may not be farfetched, given Suu Kyi's popularity.

"I've voted a few times in my life but this would be the only time we would have a chance of change. You don't even have to ask me who I voted for. Everyone votes for the same party. It's time to change," said Aung Win, 64, after casting his ballot.

Winning the election would only be the first step toward full power for Suu Kyi's party. After the polls, the newly elected members and the military appointees will propose three candidates, and elect one as the president. The other two will become vice-presidents. That vote won't be held before February.

Suu Kyi cannot run for president because of a constitutional amendment that bars anyone with a foreign spouse or child from holding the top job. Suu Kyi's late husband and sons are British.

Also, the military is guaranteed key ministerial posts -- defence, interior and border security. It is not under the government's control and could continue attacks against ethnic groups. But critics are most concerned about the military's constitutional right to retake direct control of government, as well as its direct and indirect control over the country's economy.

Richard Horsey, an independent Myanmar analyst, said that given the powers it has, the military will not be too perturbed about allowing transfer of power to the NLD if it wins.

"But that's not to say the relationship between the new administration and the military will necessarily be a strong one. It's very difficult to imagine that anyone will be running the country without having the support of the military," he said.

There are concerns about the vote's credibility, because for the first time about 500,000 eligible voters from the country's 1.3-million-strong Rohingya Muslim minority have been barred from casting the ballot. The government considers them foreigners even though they have lived in Myanmar for generations. Neither the NLD nor the USDP is fielding a single Muslim candidate.

With some 11,000 local and international monitors overseeing 40,000 polling stations, election observers said they are hopeful any attempts at systematic wrongdoing will be spotted.

"We won't be everywhere, but we'll have a good sample," said Jonathan Stonestreet, who heads a team from the Carter Center, which has overseen more than 100 elections across the globe.

The elections are also seen as a chance for Suu Kyi to reclaim what she sees as her destiny.

Her party won just over 80 per cent of parliamentary seats in the 1990 general election, even though she and her top deputy were under house arrest. A shocked army refused to seat the winning lawmakers, with the excuse that a new constitution first had to be implemented -- a task that ended up taking 18 years to accomplish.

Suu Kyi was again under house arrest for the next general election in 2010, which the NLD boycotted because it considered election laws unfair. Still, the vote ended the junta era -- which had begun in 1962 -- and ultimately installed President Thein Sein, a former general who began instituting political and economic reforms to end Myanmar's isolation from much of the world and jumpstart its moribund economy.

Election laws were eased, and in 2012, the NLD agreed to contest a series of byelections, winning most of the seats at stake. Suu Kyi was elected a member of parliament for a suburb of Yangon.

She appears set to march back into Parliament.

"I think the country will be better if the party we chose or the leader we chose actually becomes the leader. I'm voting for NLD. That's my choice," said first-time voter Myo Su Wai.

------

Associated Press journalists Robin McDowell, Grant Peck, Denis Gray and Jerry Harmer contributed to this report.