It’s a maxim drilled into us from the start of our careers: a reporter is never supposed to become the story. Stay objective.

That was my plan when W5 set out to make 48 Hours, a documentary on how Vancouver is handling its intense, deadly overdose crisis.

But when our interview subject, an injection drug user, dropped to the ground and passed out in the middle of the shoot, I couldn’t be objective. My first thought was: what can I do to save her life?

It was a jarring moment, but perhaps we shouldn’t have been so surprised. On average, five people died a day in December from drug overdoses in B.C. Many from opioid drugs cut with strong, cheap substances including fentanyl.

Death is all around. Dozens of 9-1-1 calls summon paramedics and firefighters to emergencies in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside every day. We had just travelled with a paramedic in a specialized unit, Brian Twaites, to see that minutes after he clears one call, he’s on to another.

An overdose can kill because the drug stops someone from breathing.

“For someone who’s never seen it before it’s frightening. They are blue because they are cyanotic due to lack of oxygen. They’re not breathing,” Twaites told me.

Twaites’s most powerful weapon against death is the opioid antidote drug, Narcan. That’s the trade name for Naloxone. And on almost every call we saw him or another paramedic use it at least once.

One of Vancouver’s innovations to battle the overdose epidemic is to give Narcan out to users themselves. The logic is, if a drug user passes out, but his friend has a Narcan kit, it’s better to use it fast. Then when paramedics arrive there’s a better chance the patient will survive.

Drug users call out “Narcan!” when there’s a potential overdose, and those with the kits come running.

Citizens groups also have Narcan, like the Overdose Prevention Society on Hastings Street, which has a room where drug users can inject. The group teaches its volunteers how to use it.

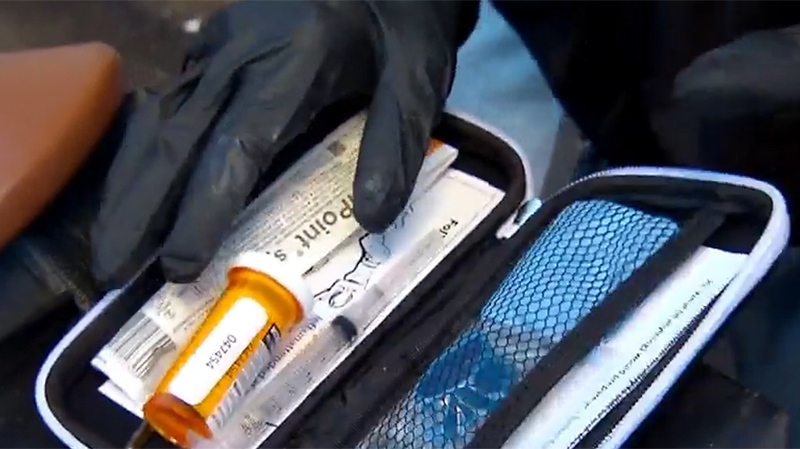

OPS head Sarah Blyth handed me a kit to use. Unzip the small black case and you find three retractable needles and three glass vials containing the heroin antidote.

“For reversal of opioid overdose,” the kit says. “Inject 1ml intramuscularly. If no improvement in 3-5 minutes, inject an additional 1ml.”

Blyth trained me, just like she trains her volunteers: on a rolled-up fleece blanket with duct tape. It was my job to snap the glass vial, fill the needle, get rid of the air bubbles, and inject.

In a controlled environment, it’s not complicated. But that night, things weren’t so controlled. We had been invited to see two women on a nightly ritual, shooting drugs. They thought they were using heroin, but couldn’t know for sure.

One of them, Patricia, absorbed it well; the other, Jessica, started dancing in the alley. Then her movements became more erratic. She started flailing.

And then she was on the ground. Not moving. I couldn’t see her breathing either.

One of us got our cell phone out to call 9-1-1. Patricia didn’t have Narcan. But I still had the kit from the earlier demonstration. We’d used one glass vial and one needle but there were two left. So I dropped my plan to be the impartial observer, and started to prep the needle.

As I was doing that, Patricia ran over to see if her friend was OK. She shook her. And she woke up. She was lucky.

I didn’t have to use the needle. But it showed me something more: the panic and fear in a population of Canadians where death can strike any time.

And you can’t feel that by being objective.