TORONTO -- Effy Zarabi came to Canada from Iran in 1991 with her family. She was nine, and her parents were eager to escape their war-torn country and give their three children a better life.

Effy quickly learned English and by the time she was a teenager, knew she wanted a career protecting people, especially in this new country that had welcomed her family.

“It was in my early teens. I’d always been around strong, positive women and I’ve always kind of connected that with the police,” said Zarabi, in an interview with W5, about her decision to seek a career in policing. “It’s an honorable career. So it was just always something that I wanted to do from a young age.”

Getting into college, working hard and volunteering in her community was just part of her journey to becoming a police officer and wearing a uniform and badge she coveted.

“I was a Big Sister; And one of the things I wanted to do to gain experience was working at Toronto Community Housing. Because it’s kind of as close to policing as you can get.”

By the year 2008, Effy became a constable in the biggest municipal police force in Canada, the Toronto Police Service.

“Oh it was the proudest (moment), it was the best thing ever,” said Zarabi, recalling the first time she put on her uniform. ”It’s the moment you feel like, ‘Yes I finally made it. All the hard work paid off.’ You just feel so accomplished.”

It didn’t take long, however, for red flags about sexual harassment and discrimination that Zarabi claims she began seeing in police college, to also send up warning signs at her new workplace.

She alleges that while working in the Toronto Police Service, she experienced a steady barrage of unwanted sexual advances, racially explicit materials and inappropriate and sexualized messages, some targeted directly at her.

“I think everybody would say, well you knew what you're getting yourself into,” Effy recalled, “but you really don’t. You don’t know until you get there.”

The claims Zarabi is speaking out about aren’t unlike those from over 3,000 female RCMP officers. In 2016 they won a massive victory when the RCMP settled in a class-action lawsuit that claimed they had faced sexual harassment, bullying and gender discrimination.

In the wake of that landmark settlement, other female officers in Canada started coming together, to speak out – a group of 12 in Waterloo, Ontario; another 14 in Calgary – bound together by their experiences and buoyed by the hope that in numbers their voices might be heard.

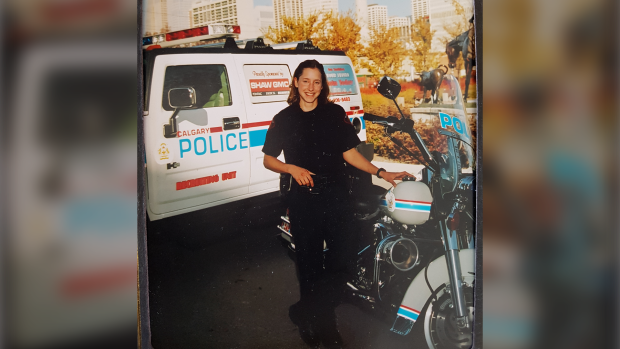

Jen Magnus was one of those female officers. As a constable for the Calgary Police Service, she also says she endured ongoing sexual harassment during her 14 years in uniform. Magnus says when she spoke up or tried to make changes, it got worse, so she gave up her badge.

When she resigned publicly in 2017, in front of a Police Commission meeting, Magnus spoke for two minutes, delivering a prepared statement.

“I have been bullied, sexually harassed, degraded and chastised,” she said, shaking and on the verge of tears. “I did not leave the Calgary Police Service, the Calgary Police Service left me. “ And then she collapsed, her head in her hands.

Magnus now focuses her attention on research. Her PhD dissertation is entitled “The Influence of a Masculine Culture in Policing.” W5 asked her whether harassment and abuse faced by female officers in this country is systemic.

Her response: “Absolutely, it is. To this day, I have a friend who’s still on the job, she hears horrific stories; she is trying to help them (female officers) but they are so fearful. So they stay quiet. It’s heartbreaking, but I understand.”

Silence is a big reason there aren’t solid statistics on this issue in Canada. It’s why third-party consultants are now being brought in to conduct impartial workplace reviews, ensuring safety for all who contribute.

A review was done for the Calgary police in 2013. The Toronto Police Service is conducting one now, expected to be complete in the spring of 2020.

W5 approached police chiefs across Canada and received some very candid responses about the culture they say they’re committed to changing. One of those chiefs was Bryan Larkin from the Waterloo Regional Police.

“It’s not perfect, it’s not where I want it to be, but I do believe we’re heading in the right direction,” said Larkin, who went on to discuss next steps.

“I think that, you know, it’s become the big focus for police leaders, is what do we want our profession to be? How do we want to reflect society? And I do believe that policing always has the opportunity to be an ambassador, to be a leader, to be a change.”

Effy Zarabi, the young girl who came to Canada and realized her dream of being a police officer, is now on stress leave. She and two other female officers threatened to sue the Toronto Police Service for enabling a “toxic, racist and sexist culture.”

That threatened lawsuit fizzled out when the other two officers settled and signed non-disclosure agreements.

Effy wanted to remain vocal, and is now bringing her claims to the Human Rights Tribunal of Ontario. Despite facing obstacles, she says she still has hope for the career she built.

“You have to be optimistic. You have to think positive. You have to believe in change. You have to, you know, keep reminding yourself of why you’re fighting the fight. Even though it’s hard, you know, you try. You have to.”