Indian envoy warns of 'big red line,' days after charges laid in Nijjar case

India's envoy to Canada insists relations between the two countries are positive overall, despite what he describes as 'a lot of noise.'

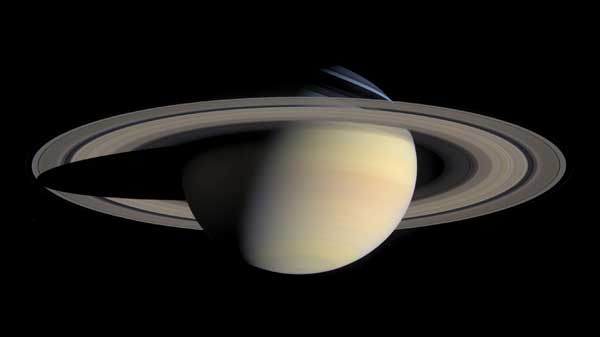

An ancient moon which was torn apart after it spun too close to Saturn may be the cause of the planet’s tilted rings, according to new research.

Saturn’s lean has always been clear through its rings, which spin around the planet at a 26.7-degree angle compared to the planet’s orbit around the Sun.

While this was long thought to be connected to the gravitational force of Saturn’s neighbour, Neptune, due to how closely the spin of Saturn aligns with the pattern of Neptune’s orbit, astronomers now believe that connection between the two planets has since been broken.

But if Saturn isn’t tilting to pull toward Neptune, what is the reason behind its current tilt? And could it be connected to the relatively recent formation of Saturn’s rings, which have previously been estimated to be only 100 million years old?

Astronomers believe they have found an explanation that could answer a number of these unexplained Saturn anomalies: an extra moon which died so the rings could form.

In a new study published Thursday in the journal Science, authors have dubbed this moon “Chrysalis.”

If Chrysalis existed as moon number 84, it would’ve assisted in keeping Saturn in line with Neptune for several billion years, the study suggests.

Then, around 160 million years ago, according to researchers’ computer modelling, Chrysalis’s orbit became unstable and it grazed the planet itself — a catastrophic event which would’ve pulled the moon apart, and would also explain how Saturn was pulled from its pattern with Neptune to acquire its current tilt.

The shattered pieces of Chrysalis which didn’t fall to Saturn were then flung into orbit around it, eventually crumbling into smaller icy pieces to make up the planet’s rings.

“Just like a butterfly’s chrysalis, this satellite was long dormant and suddenly became active, and the rings emerged,” Jack Wisdom, professor of planetary sciences at Massachusetts Institute of Technology and lead author of the new study, said in a press release.

This theory patches a number of holes in previous explanations for Saturn’s orbit, rings and tilt, researchers say.

It was first suggested in the 2000s that Neptune and Saturn were bound in a gravitational association, but when NASA’s Cassini flew out to visit the planet from 2004 to 2017, its observations brought new complications.

Cassini’s observations of Titan, Saturn’s largest moon, led to the theory that this large moon was actually responsible for Saturn’s tilt, forcing it into alignment with Neptune. However, this only made sense if the gas giant’s mass was distributed in a particular way — since the planet’s composition makes it difficult for us to tell if its mass is concentrated more towards the core or not, the planet’s moment of inertia is hard to pinpoint.

Wisdom and his colleagues set out to see if Cassini’s final observations — gathered in the last moments of its existence as the spacecraft plunged towards the surface of Saturn — could shed light on the issue.

These final observations made it possible to create a gravitational field of Saturn that allowed researchers to model the way mass is distributed across the planet.

They found that the moment of inertia they’d been searching for meant that Saturn was actually slightly out of alignment with Neptune. The planets were no longer in sync.

“Then we went hunting for ways of getting Saturn out of Neptune’s resonance,” Wisdom said.

After modelling numerous scenarios, the team discovered that the math balanced out if a new moon was added and then subtracted in a cataclysmic event.

They theorize that Chrysalis’ orbit became chaotic between 100-200 million years ago, and that after it had some near misses with some of the other large moons such as Titan, it grazed by Saturn itself, travelling too close to survive the encounter.

Chyrsalis would’ve had to be about the size of Iapetus, Saturn’s third-largest moon, to explain how its destruction and loss could’ve pulled Saturn out of resonance with Neptune.

“It’s a pretty good story, but like any other result, it will have to be examined by others,” Wisdom says. “But it seems that this lost satellite was just a chrysalis, waiting to have its instability.”

India's envoy to Canada insists relations between the two countries are positive overall, despite what he describes as 'a lot of noise.'

With Donald Trump sitting just feet away, Stormy Daniels testified Tuesday at the former president's hush money trial about a sexual encounter the porn actor says they had in 2006 that resulted in her being paid to keep silent during the presidential race 10 years later.

The U.S. paused a shipment of bombs to Israel last week over concerns that Israel was approaching a decision on launching a full-scale assault on the southern Gaza city of Rafah against the wishes of the U.S.

Footage from dozens of security cameras in the area of Drake’s Bridle Path mansion could be the key to identifying the suspect responsible for shooting and seriously injuring a security guard outside the rapper’s sprawling home early Tuesday morning, a former Toronto homicide detective says.

A chicken farmer near Mattawa made an 'eggstraordinary' find Friday morning when she discovered one of her hens laid an egg close to three times the size of an average large chicken egg.

Susan Buckner, best known for playing peppy Rydell High School cheerleader Patty Simcox in the 1978 classic movie musical 'Grease,' has died. She was 72.

Accused killer Jeremy Skibicki could have a challenging time convincing a judge that he is not criminally responsible for the deaths of four Indigenous women, a legal analyst says.

A Calgary bylaw requiring businesses to charge a minimum bag fee and only provide single-use items when requested has officially been tossed.

Two Nova Scotia men are dead after a boat they were travelling in sank in the Annapolis River in Granville Centre, N.S., on Monday.

An Ontario man says he paid more than $7,700 for a luxury villa he found on a popular travel website -- but the listing was fake.

Whether passionate about Poirot or hungry for Holmes, Winnipeg mystery obsessives have had a local haunt for over 30 years in which to search out their latest page-turners.

Eighty-two-year-old Susan Neufeldt and 90-year-old Ulrich Richter are no spring chickens, but their love blossomed over the weekend with their wedding at Pine View Manor just outside of Rosthern.

Alberta Ballet's double-bill production of 'Der Wolf' and 'The Rite of Spring' marks not only its final show of the season, but the last production for twin sisters Alexandra and Jennifer Gibson.

A mother goose and her goslings caused a bit of a traffic jam on a busy stretch of the Trans-Canada Highway near Vancouver Saturday.

A British Columbia mayor has been censured by city council – stripping him of his travel and lobbying budgets and removing him from city committees – for allegedly distributing a book that questions the history of Indigenous residential schools in Canada.

Three men in Quebec from the same family have fathered more than 600 children.

A group of SaskPower workers recently received special recognition at the legislature – for their efforts in repairing one of Saskatchewan's largest power plants after it was knocked offline for months following a serious flood last summer.

A police officer on Montreal's South Shore anonymously donated a kidney that wound up drastically changing the life of a schoolteacher living on dialysis.

This Oct. 6, 2004 photo provided by NASA, taken by the Cassini Saturn Probe, shows the planet Saturn and its rings. (AP Photo / NASA)

This Oct. 6, 2004 photo provided by NASA, taken by the Cassini Saturn Probe, shows the planet Saturn and its rings. (AP Photo / NASA)