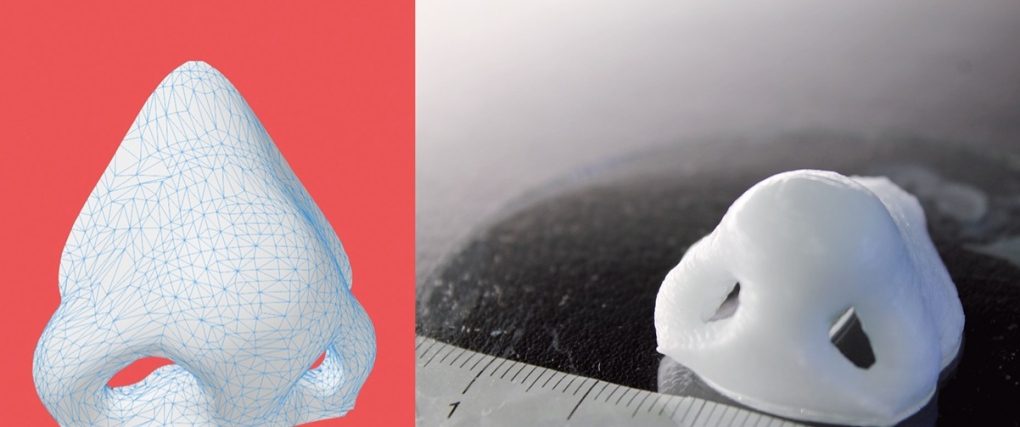

In just 16 minutes, it's possible to print out living cartilage to give you a new nose, thanks to scientists at the Federal Polytechnic University in Zurich (ETH Zurich).

They call the process bioprinting, because they use actual cellular materials -- in this case living cartilage cells, mixed with biopolymers.

In case you shatter your nose, the doctors would biopsy your cartilage, in either the knee, finger, ear splinters or pieces of your broken nose to mix them with the biopolymers and print out a new, intact nose.

The research team says that after the nose has been surgically implanted, the body's cartilage cells break down the polymers, and about two months later, your new nose would become impossible to distinguish from the old one, if it was still there.

Traditional nose jobs use silicone implants, which are sometimes rejected by the body.

Using your own cells carries less risk of rejection, and young patients who may still be growing benefit from using their own cartilage, which grows with them, according to the researchers.

In an interview, a representative of the research team says they are in the process of submitting their paper for publication.

The Zurich team says that printed cartilage transplants will likely be applied first to treating injuries to the knees and ankles.

In December, researchers at Columbia University Medical Center announced that they were able to successfully implant 3D-printed cartilage in sheep.

Sheep were used in the experiment because their knees closely resemble those of humans.

In this particular case, the researchers replaced the meniscus, which is a piece of C-shaped cartilage, the tearing of which is one of the most common knee injuries, according to the Mayo Clinic.

The meniscus regenerated in four to six weeks after the 11 sheep had their operations, and three months later, they were walking normally.

Timewise, the Swiss research team has an edge on the Columbia team, for their implants take just 16 minutes to print, whereas the Columbia meniscus takes a half hour.

The Columbia paper was published in the online edition of Science Translational Medicine.