WASHINGTON -- Hillary Clinton's defenders say she's sufficiently explained why she set up a do-it-yourself home email system when she was secretary of state, insist there's nothing to see here, and it's time to move on.

You know who disagrees?

The senior-most freedom-of-information official in the executive branch of the United States government for over a quarter-century, whose job it was to help four administrations -- including the Clinton White House -- interpret the Freedom of Information Act, offer advice, and testify before Congress on their behalf.

Daniel Metcalfe doesn't buy her explanation. In fact, he calls it laughable.

"What she did was contrary to both the letter and the spirit of the law," says Metcalfe, the founding director of the Justice Department's Office of Information and Privacy, which advised the rest of the administration on how to comply with the law. Metcalfe ran the office from 1981 to 2007.

"There is no doubt that the scheme she established was a blatant circumvention of the Freedom of Information Act, atop the Federal Records Act."

Metcalfe says he doesn't have any partisan axe to grind. He's a registered Democrat, through steadfastly non-partisan. He says he was embarrassed to work for George W. Bush and his attorney general, and left government for American University, where he now teaches government information law and policy.

And he says what Clinton did was wrong. Here's how he would have reacted if he'd heard about a cabinet member in his day setting up a personal email system -- and deciding what got deleted and what got preserved as a government record.

"I would've said, 'You've gotta be kidding me," he said.

"You can't have the secretary of state do that; that's just a prescription for the circumvention of the FOIA. Plus, fundamentally, there's no way the people at the archives should permit that if you tell them over there."'

He said he knows from working under the Clintons that Hillary -- secretary of state, senator, 2016 presidential hopeful and lawyer -- understands the Freedom of Information Act.

Clinton's defenders point out that there was nothing in the law explicitly forbidding what she did. Public records were to be preserved, but it didn't say personal emails were public records. Until a 2014 change to the law, it didn't say those personal-account emails had to be turned over.

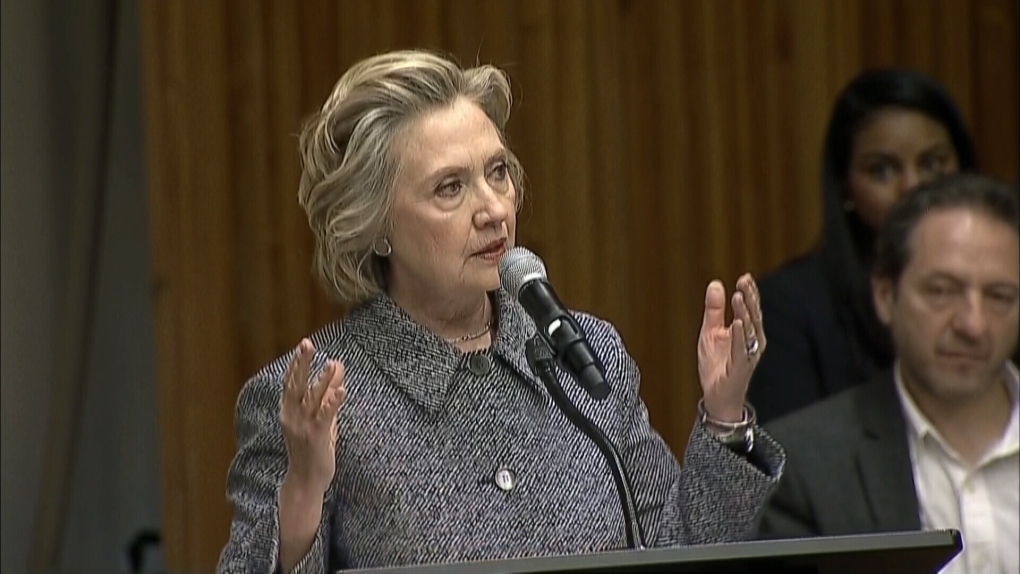

Clinton told a news conference that she deleted about half of her 60,000 emails -- personal messages about her daughter's wedding, mother's funeral, and yoga routines.

She said there was also correspondence with her husband. Given that he ran a multibillion-dollar charitable foundation that received foreign donations while she represented the U.S. abroad, even their correspondence could be of interest to researchers, journalists and political opponents.

Metcalfe examined a transcript of her press conference, provided by The Canadian Press.

And he dissected it Wednesday, point by point, annotating it in 23 places where he called her statements "deceptive," "grossly misleading" and impossible to verify.

His overall conclusion from her public appearance: "Her suggestion that government employees can unilaterally determine which of their records are personal and which are official, even in the face of a FOIA request, is laughable."

There were signs Wednesday that the email storm could linger a while:

--The Associated Press filed a lawsuit against the State Department to force the release of email correspondence and documents from Clinton's tenure as secretary of state. The suit followed repeated requests filed under the U.S. Freedom of Information Act that have gone unfulfilled.

--A spokesman for Barack Obama dodged queries about whether the president approved of her email arrangement. He also referred questions about the process for deciding what got deleted to the Clinton team.

--The Clinton team, meanwhile, was in fighting spirits. Its willingness to push back was illustrated in a feisty letter from the head of the pro-Clinton group Media Matters.

David Brock dismissed a demand that she turn over her email server. He called it "Orwellian" -- and in a letter to the Republican congressman who made the demand, he asked that congressman to lead by example and release his own email.

This was after the chairman of a House committee investigating the deadly 2012 attacks in Benghazi, Libya, announced that he wants a neutral third party, such as a retired judge, to review Clinton's email server and determine which of her emails should be made public.