OTTAWA – Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has pledged to eradicate all drinking water advisories in First Nations communities by March 2021. With three years left and more than 60 communities still turning to alternative water sources for drinking, bathing and cooking, critics are weary about the pace and scope of work left to be done.

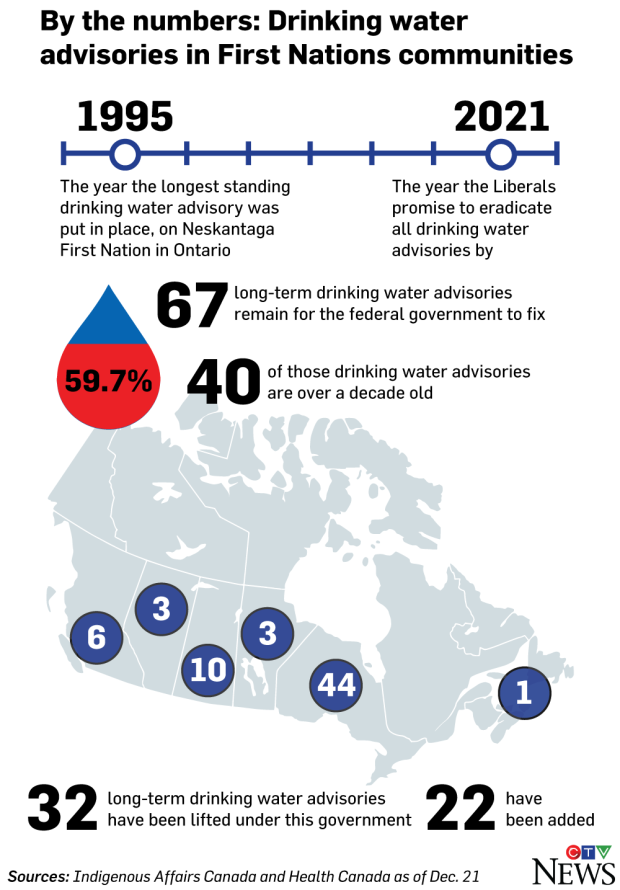

As of Dec. 21, there were 67 long-term drinking water advisories in effect for public water systems managed by the federal government. These drinking water warnings have been in place for over a year.

There are an additional 18 communities that are currently at risk of developing long-term drinking water advisories, meaning they’ve had water issues for between two and 12 months.

Since forming government, the Liberals have lifted 32 drinking water advisories. However, 22 new advisories have been added in that time, according to the Indigenous and Northern Affairs department.

On the Liberals' mandate tracker, the promise—which is wrapped into a category about improving essential Indigenous infrastructure—is listed as “underway with challenges.”

"There's a sense of you make two steps forward, one step back," said Conservative Indigenous affairs critic Cathy McLeod. She said for every two communities that come off a drinking water advisory, it seems another warning is issued, making the 2021 target "an extreme challenge" to meet.

Graphic by Nick Kirmse / CTVNews.ca

Graphic by Nick Kirmse / CTVNews.ca

40 water warnings in place for a decade or more

The government's most recent projection was that by the end of 2017 there would be 65 advisories left to lift, dropping to 37 in 2018. The projection prior to the latest update was more optimistic, showing the number of unclean water sources left to clear up dropping slightly.

The longest-standing boil water advisory is on the Neskantaga First Nation in northern Ontario. It's been in place since 1995, for the community of around 240 people. The construction of a replacement treatment system is underway and the government estimates the problem will be solved by October, 2018.

Forty communities across Canada have been dealing with drinking water limitations for a decade or more.

There are three types of drinking water advisories:

- 'Boil water' advisories, which requires the water to be boiled before consuming or for cooking or cleaning;

- 'Do not consume' advisories, which means the water cannot be consumed or used for cooking or cleaning, but adult bathing is okay; and

- 'Do not use' advisories, where people cannot use the water for any reason.

In any case, the advisories force community members to find alternate water sources, adding an extra step to basic daily functions like bathing a child, or cooking dinner.

The water advisories are based on quality tests, and are issued by First Nations leadership on reserves, and municipal or provincial/territorial governments off-reserve.

Health Canada also tracks the drinking water advisories in First Nations communities where the public water source is privately owned, by a gas station, for example. When these warnings are added to the ones the federal government is responsible for managing, the total number of long-term and short-term advisories jumps to 136, as of Nov. 30, 2017. This number excludes advisories in British Columbia, which are tracked by the First Nations Health Authority, and the Saskatoon Tribal Council, which monitors its own.

Over $1 billion short

To tackle the issue, the Liberals earmarked $1.8 billion in the 2016 budget over five years to fix and maintain the on-reserve water and wastewater infrastructure, as well as training water system operators. Another $141.7 million over five years is going into Health Canada’s coffers to improve the monitoring and testing of drinking water on reserves.

The government says its approach to seeing First Nations communities finally having clean drinking water will be successful because unlike past governments, the Liberals are committing long-term funding.

The drinking water advisories force community members to find alternate water sources, adding an extra step to basic daily functions like bathing a child, or cooking dinner. (CTV News)

But in a Dec. 7 report, the Parliamentary Budget Officer (PBO) found that the money the federal government is planning to spend to clean up these communities’ water systems will not be sufficient.

The PBO estimated that the minimum spending required to meet the current and future needs of these First Nations is $3.2 billion, meaning the Liberals are looking at coming up over a billion dollars short. Depending on population growth, what they’ve planned to spend will only end up covering between 54 and 70 per cent of the cost needed.

When the report was released, Indigenous Services Minister Jane Philpott said she’d make sure the government was "appropriately resourced" to fulfill its commitment.

In an interview with CTV News.ca, Philpott said while she will take into consideration the PBO’s findings and is committed to seeing the advisories lifted, she couldn’t say more money will be coming.

'That’s appalling, and that's Canada'

The PBO's report was done on the request of NDP MP and Indigenous and northern affairs critic Charlie Angus.

He's worried that, as has happened with past governments, the money pledged to once and for all fix the drinking water deficiencies in First Nations communities will be spread too thin.

Angus told CTV News.ca that over the years he's watched governments commit what should be enough money to solve the problem. But once they realize the amount won’t cut it, instead of spending more, they spread it too thin in an effort to meet their pledge, he said.

"We end up with the same old… they build systems that aren’t sufficient, they do things on the cheap, the systems don’t work, and then the cycle repeats itself," he said in an interview.

My first political battle in Ottawa was over the water crisis in Kashechewan. It was a frightening time for the community. I remember the promises made to end the water crisis once and for all. And yet, 13 years later Indigenous communities are still waiting. pic.twitter.com/yoy1QXQDee

— Charlie Angus NDP (@CharlieAngusNDP) December 11, 2017

Former Liberal prime minister Paul Martin put $1.9 billion into building brand new water treatment plants across First Nations reserves during his 2003-2006 government.

"That should have settled it," Angus said. "So, he [Trudeau] made a grand gesture… but unless you’re going to sit down and do this in a coherent, systematic manner, putting the full resources, at the end of the day we’re not going to be all that much further ahead."

The issues with water in First Nations communities are complex, and different depending on where the communities are located and where they source the water from. For some, the water treatment plants aren’t sufficient to meet the needs of the community. In others there’s a lack of training to keep the plants humming, and sometimes, when little fixes are needed the federal government is slow to step in.

Angus said he was speaking with a group of young First Nations people from northern Ontario about the water and a few young women told him they didn’t want to wash their hair because they got burns from the amount of chlorine that had to be put in the water to clean it.

"That's appalling, and that’s Canada," he said.

'It’s been confusing and it's been long'

Serpent River First Nation in Ontario was one of the communities that the government recently touted in a press release as having their drinking water advisory lifted. However, Chief Elaine Johnston told CTV News.ca that their water woes aren’t over yet.

Situated between Sudbury and Sault St. Marie on the northern edge of Lake Huron, the community of 370 people has had a new water treatment system since 2015, but has only been able to start drinking the water a few months ago.

Shortly after the ribbon cutting on the multi-million dollar water treatment plant, it was discovered that the level of trihalomethane (THM) in the water was nearly double the safe consumption limit. The filter membranes used by the plant weren’t adequately filtering it out of the source water.

Johnston compared learning this news to a balloon deflating.

Serpent River Chief Elaine Johnston, shown here at a celebration in her community in May. (Joe Maurice / Twitter)

For two years the community relied on bottled water for drinking and cooking because the THM could not be boiled out of the tap water, and the fix was not quick. Serpent River had to bring in different filters from outside of Canada.

The new membranes are working and Serpent River's water is finally drinkable, though the community is currently in talks with the government over another $1 million to deal with a chlorine treatment needed for the Lake Huron source water, to target zebra mussels.

"It's been confusing and it’s been long," Johnston said of navigating the federal government's process for getting clean water.

Even though the water has been cleared for public consumption, there are still people who don’t trust what’s coming through their taps.

"We have to build that trust with them," Johnston said.

Based on what Serpent River has gone through, she doesn’t think the 2021 target is realistic unless the federal government changes the way Indigenous Affairs manages their cases and reduces the red tape involved.

She also thinks because so many Canadians take clean drinking water for granted, it’s easy to forget that there are many people who don’t have the ability to turn on the tap and not think twice.

"Our community, we're grateful," Johnston said.

Training water operators

During Serpent River's 'do not use' water advisory, the water treatment plant operators delivered the clean water. They were also the ones who had to do other community maintenance, like snowplowing. Johnston described them as the local "jack of all trades."

Part of the federal spending to lift the drinking water advisories is on training water and wastewater operators who will be able to keep on top of their communities’ new water systems once installed.

In Dryden, Ont., there is a training school solely dedicated to this. The Keewaytinook Centre of Excellence teaches hands-on water plant skills, to certify local water operators. It’s tied to the Safe Water Project, a First Nations initiative to eliminate boil water advisories in First Nations communities.

In 2016 the federal government put $4 million towards the project.

In its 2017 report, "Glass Half Empty," the David Suzuki Foundation called the Safe Water Project "unique" and praised it for having directly helped end local boil water advisories.

"It takes into account the context of each First Nation rather than taking a one-size-fits-all approach," the report said.

Angus called it an "amazing" example of how Indigenous people are working to improve conditions for themselves.

But McLeod cautioned that in some communities, the people who get trained as water operators end up leaving because they can get paid more for their skills in another community, making retention an issue.

"We’re looking at how we can provide more training and also retain these people in communities," Philpott said.

'Every one is going to get lifted'

Philpott is hoping to see a sharper drop in the number of communities that can’t drink tap water in 2018, now that those with long-term advisories are working on individualized plans with the federal department to see their water cleaned up.

Philpott said she has instructed her officials to keep her appraised of the progress, and update her if there’s slippage.

Minister of Indigenous Services Jane Philpott speaks at the Assembly of First Nations Special Chiefs Assembly in Ottawa on Wednesday, Dec. 6, 2017. (Justin Tang / THE CANADIAN PRESS)

Her experience living in West Africa for nine years, where she wasn’t able to turn on the tap and drink, gives her an understanding of what these communities face on a daily basis, Philpott said.

"Access to clean drinking water is a fundamental basic need. Water is essential to survival, and it has to be clean water so that people can stay healthy," said Philpott. "Every one (advisory) is going to get lifted. Some of them… will be lifted in the next year, and others will take a couple more years yet."

It's expected the federal government will provide a public update in January on the progress lifting these drinking water advisories.