OTTAWA -- Rob Oliphant believes he was uniquely suited to chair the special joint parliamentary committee that wrestled with the emotionally and politically charged issue of an individual's right to seek medical help to die.

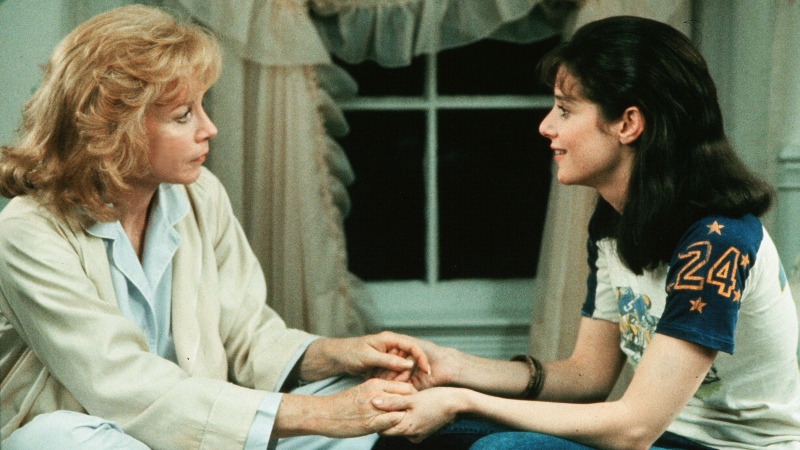

As a United Church minister for 30 years, the Liberal MP has sat "many, many times" at the bedsides of dying individuals, offering prayers, counsel, comfort or just an ear to listen to their final thoughts.

And he's helped guide family members as they agonize over whether to turn off life support machines that are keeping a loved one breathing.

Such cases, he says, raise social, theological and ethical questions which "demand you to have an understanding of what is compassion and what is pain and what is suffering and how do you make sense of this thing called life."

Most people, he muses, don't like to talk about death or confront profound questions like what constitutes quality of life or how to deal with unbearable suffering.

"These are questions that I've had to deal with my whole life," Oliphant said in an interview.

The issue of medical assistance in dying is deeply personal for everyone, each person's views informed by their beliefs, their own experience with death and suffering, their fears and hopes about the manner in which they will meet their own end.

And it's no different for the politicians who will ultimately determine how broadly or narrowly to give effect to the Supreme Court's ruling that the law must recognize the right of consenting adults enduring intolerable mental or physical suffering to seek medical help to end their lives.

Oliphant's committee this week came down on the side of permissiveness, recommending a regime that would make it relatively easy for consenting adults to obtain medical assistance in dying, extend it through advance directives to people diagnosed with capacity-impairing diseases like dementia and, eventually, give mature minors an equal right to choose a doctor-assisted death.

For Oliphant, the recommendations flow from his experience at the bedsides of dying parishioners, where he's sometimes found he has "more intimacy than family because people will tell you things that they won't tell their own family."

"Most people I have talked to express more fear of living with a debilitating disease than dying from it," he says.

"They really are anxious about the journey, they're anxious about pain, they're anxious about prolonging and they would like some kind of way of saying goodbye and knowing that that would be when they're saying goodbye."

Oliphant believes that just knowing they have the option to choose medical assistance to end their lives will be a comfort to people who are suffering. But he doubts many will actually follow through.

"I really believe that there's a stage in a dying person's cycle where they're very nervous about potential suffering ... and they doubt their own capacity to handle it and they really hope there'll be something to help them," he says.

"I really think that the incidence of using medical assistance in dying will be quite small, that people will generally want to hold onto life and they will recognize that their suffering isn't as bad as they thought it was going to be and they'll actually have more courage because they know they have the option."

For those facing a diagnosis of dementia or other degenerative conditions that rob them of their mental capacity, Oliphant says the fears are different: loss of dignity and loss of identity.

"I think that's why people are looking for advance directives because they know there'll be a moment in their life that they're no longer themselves and they don't want that."

While he respects that, Oliphant says dementia is not personally "a big worry" for him, he's "kind of interested to know what that experience would be like, whether there is a kind of cognitive capacity that we just don't know about that's there."

Still, if there's anything he's learned in his ministry, it's that life is "an individual journey" and each person must come to terms with their mortality in their own way.

"I put life at the top of the list of values but it has to have quality associated with it, not just a quantity, that life that is not acceptable to someone then becomes not life."