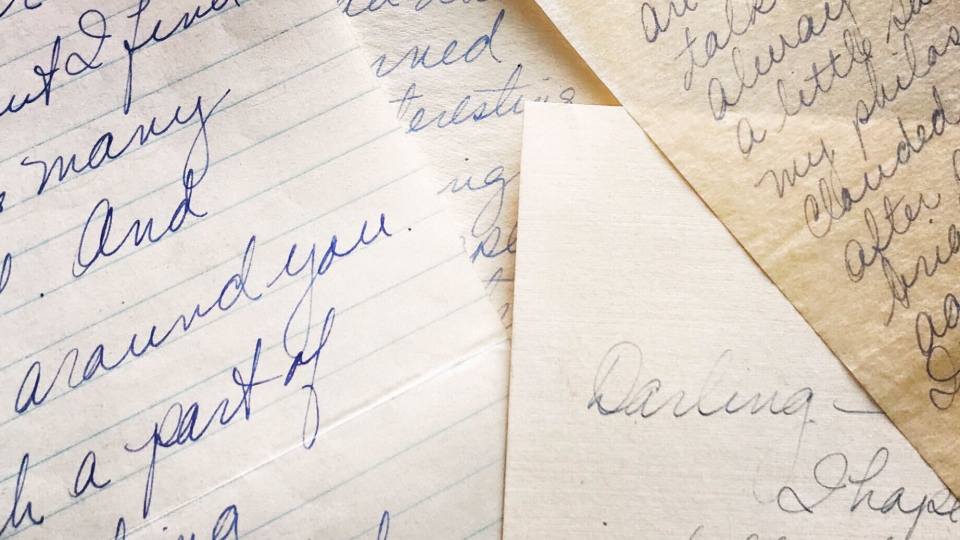

The search for clues about why people choose to die by suicide often starts with the words they leave behind. Dr. Rahel Eynan, a scientist with the Lawson Health Research Institute in London, Ont., is unravelling such mysteries one heart-wrenching note at a time.

“When I’ll open a file, in my head I’ll say, ‘Tell me your story,’” she told CTV News. “Sometimes you actually can feel the pain of the individual that wrote them.”

In a 2018 study published by The American Association of Suicidology, Eynan analyzed 383 suicide notes left by children as young as 11 and adults as old as 98 to find signs that can be used to identify and help others who are at risk.

“I’ve been invested in suicide research a long time, over 20 years,” Eynan said. “I’m trying to save lives after all -- that’s what all of this research is all about.”

‘THE PAIN WAS OVERWHELMING’

For a year, Eynan sifted through the notes, copying them out by hand because Ontario coroner’s office rules would not allow her to remove them from their files. That, Eynan says, was a “difficult” endeavour.

“It was like hearing their voices in my head,” she said. “The intensity of the emotion was great. The pain was overwhelming.”

While such notes are only left in less than half of all suicide cases, Eynan discovered some striking commonalities.

“About 57 per cent expressed love for others,” she explained. “Very few expressed that they felt loved… About 53 per cent expressed ‘sorry’ and apologies.”

Half, Eynan also found, were escaping illness, physical or psychological pain.

“They are so constricted in their thinking that they don’t see any other option -- the only option is to die,” she said.

The other half, she learned, were dealing with financial crises or heartbreak.

“It’s not exclusively women that kill themselves because they were divorced or a relationship broke down,” Eynan said. “Men are quite invested and that was very clear from the notes… And when their relationships end, that they are devastated.”

In her research, Eynan also uncovered an emerging phenomenon: 25 per cent of the suicide notes she analyzed were electronic -- primarily text messages -- and many were written by young people who had never been diagnosed with mental illness.

“Some of them were not even sent -- they were left on the phone itself,” she recalled. “But if the message is prepared and not sent, how can we then intervene in those cases?”

‘A MISSED OPPORTUNITY’

Eynan’s study provides clues on how to prevent future suicides.

“Those that left suicide notes, 10 per cent had seen their doctor the same day,” she said. “Thirty three per cent saw their doctor within that week, yet some were not assessed for suicide.”

For doctors, Eynan says that finding presents “a missed opportunity.”

“So what we can learn from that is, how can we improve primary care assessments in terms of suicide risk?” she said.

Doctors, she suggests, should actively be asking at-risk patients if they think about suicide. As for families and loved ones, “absolutely there are cues,” that they “should be alert to,” Eynan said.

Some are behavioural, such as giving away possessions or sudden changes in mood.

“Individuals that have been depressed for a long time and then suddenly they are very cheerful, they might have come to the decision that they are going to kill themselves,” Eynan explained.

Other cues can come from speech.

“Like, ‘I’m done,’ or, ‘I’m checking out,’” Eynan said. “One has to inquire, ‘What do you mean by that?’”

Such cues, she adds, should spark an immediate intervention.

“Because if there is time, let’s use the time to save a life,” she said.

But among the hundreds of suicide files Eynan reviewed for her study, more than 54 per cent left no known notes. Eynan characterizes this group as being older and having experienced “more hospitalizations, more diagnoses” than those that left words behind.

“Families were aware that they were struggling, (that) they were having challenges for a long period of time -- they didn’t need to explain,” she said. “But if it’s someone (for whom) the struggles (have) just started… they felt that they needed to explain.”

‘THEY TOUCHED MY LIFE’

For Eynan, her line of research -- listening to the dead to safeguard the living -- can be a painfully emotional experience.

“They touch my heart,” she said while choking back tears at the end of her interview. “I’m human. They were human. They left people that are hurting and if they touched my life, I’m certainly hurting because they died. And I’ve never met them, yet they touched my life.”

REACH OUT

If you need help, the Canadian Mental Health Association’s Reach Out program is a 24-7 telephone hotline and internet service for those needing to talk about issues regarding mental health. Reach Out can be contacted toll free at 1-866-933-2023 or online at www.reachout247.ca.