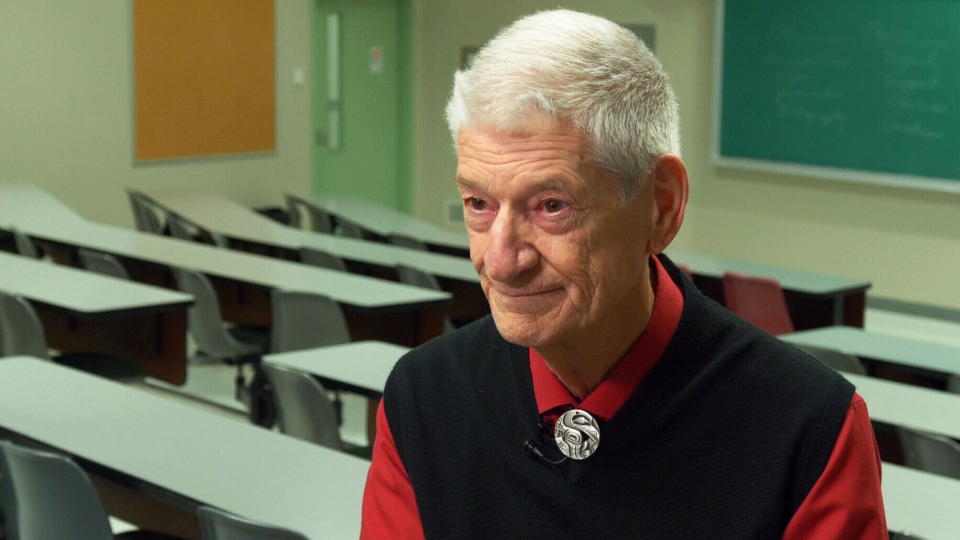

After being diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, 81-year-old Ron Robert decided to enroll in university as a personal experiment to see if education could keep the chronic neurodegenerative disease at bay.

“I thought when I was given this diagnosis, I got to change my lifestyle; I’ve got to do something about this thing,” Robert told CTV News. “I mean, I’m not just going to sit on my butt and let my brain turn to mush.”

Robert is now a first-year undergraduate student at King’s University College in London, Ont., where he takes classes twice a week in political science and disability studies. He is also one of the faces of the Alzheimer Society of Canada’s “Yes. I live with Dementia” campaign to mark Alzheimer’s Awareness Month in January. By “shining a light on the facts about people living with Alzheimer's and other forms of dementia,” the campaign aims to challenge “misconceptions so that the stigma that surrounds the disease can be reduced.”

According to the society, more than half a million Canadians are living with dementia. In less than 15 years, moreover, that number is expected to double to nearly one million.

“Too many people, they get diagnosed with something like Alzheimer’s and they think somehow it’s the end,” Robert said. “Well, it’s not an end -- it’s just a new beginning. It’s something you’ve got to work at. And actually, it’s a good thing because I was getting quite bored being retired! So this is all a new challenge for me.”

‘You don’t look like you have Alzheimer’s!’

At school, Robert has made no secret of his diagnosis with his peers, many of whom are young enough to be his grandchildren. A common response, he says, is “Well, you don’t look like you have Alzheimer’s!”

“I basically say I’m here to keep it at bay and they all think it’s wonderful,” Robert added. “They’re so receptive to it. They sort of look a bit sad at first, but then after I talk to them for a little bit, then they’re all for it.”

After a long career as both a political journalist and an aide to former Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau, Robert’s diagnosis at age 78 came as a shock -- even though two of his siblings both died with the disease.

“I should have been aware, but I was in denial just like so many other Canadians are,” Robert said. “We don’t think that we’re going to get it.”

Even how the diagnosis was delivered was jarring.

“All they told me was, number one, you have Alzheimer’s, number two, you’ve lost your (driver’s) licence and (the) conversation was over,” Robert recalled. “So you’re on your own basically and that, by the way, I’ve heard that repeated many times by people that have Alzheimer’s.”

So, Robert decided to take matters into his own hands. With no effective medication to stop Alzheimer’s, Robert instead thought that academic assignments and deadlines would help keep his mind sharp. The strategy seems to be working.

“I feel really good,” he said. “The short-term memory is terrible; long-term memory has improved. I feel better mentally, and I think that’s a big important part too. You’ve got to be upbeat.”

And if Robert gets disorientated or lost on the sprawling Southwestern Ontario university campus, his peers always put him back on track.

“One or two or three of them can come over and say, ‘Are you OK? Can we help you?’” Robert said. “You know, that kind of caring means a lot to people like me.”

‘Just like any other student’

Dr. Jeff Preston, who teaches Robert’s disability studies class, describes the octogenarian as “very eager,” “passionate” and “just like any other student.”

“One of the greatest things about Ron being in the classroom is he brings a different perspective: a perspective of his life, but also a perspective of somebody who has a… diagnosed disability,” Preston told CTV News. “I’m so thankful that Ron is stepping forward and saying, ‘I’m going to add my voice… to this fight to think differently about Alzheimer’s and dementia,’ to say, ‘This isn’t the end, this is just the start of a new chapter.’”

As for Robert, he hopes his example will inspire more research into living well after receiving an Alzheimer’s diagnosis.

“What annoys me is all of the money that goes into research on Alzheimer’s, it seems it’s always about the pills,” he said. “I haven’t seen one study yet about how to handle it. I’ve written a brief paper recommending a study be done based on what I’m doing and it’s really hard to get the researchers interested in it.”

And what started as a way to keep his mind active has also given him some new goals too.

“I want to cross that stage with some of those great, bright young adults… to graduate,” Robert said. “I’m hoping I’m the beginning of a wave -- I hope that all those people out there listening that have given up on Alzheimer’s will just get off their butts and join me out here!”