The secret to restoring age-related memory loss – at least temporarily – could be through a series of brief, painless pulses of electricity to the brain.

Several studies have demonstrated how electric stimulation can revive aging brains and improve failing memory.

Most recently, a study published in the medical journal Neurology found that regular electric stimulation to the brain could restore memory loss among seniors to a level comparable to healthy young adults.

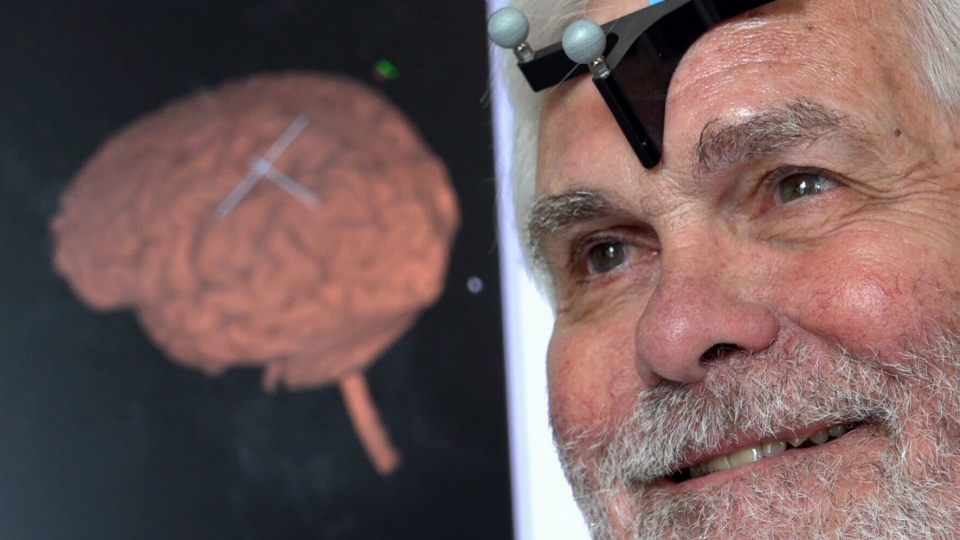

A team from Northwestern University in Illinois conducted the small pilot study on 15 seniors. For five days, the seniors underwent 30 minutes of transcranial magnetic stimulation, or TMS, a procedure administered from a non-invasive device that uses magnetic fields to stimulate nerve cells in the brain.

The stimulation specifically targeted the brain regions linked to the hippocampus, the area of the brain that stores memories. During the procedure, a paddle-like instrument containing a metal coil emitted a magnetic field next to a patient’s head, giving the sensation of a light tapping.

Participants were given the memory test at the start of the study, one day after treatment ended and again one week later. Researchers found that, when tested one day after the treatments ended, participants’ ability to recall memories improved 31 per cent compared to their abilities at the start of the study.

MRI imaging also showed more activity in the parts of the brain related to memory formation.

One day after the treatment ended, the seniors – who had an average age of 72 -- demonstrated near-normal memory scores when compared with healthy 25-year-old subjects.

The study was small, and the improvements temporary, but lead investigator Joel Voss, an associate professor at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, called his team’s findings “fairly remarkable.”

“We essentially rescued their aging memory impairment up to the level of young, healthy adults performing the same memory task,” Voss told CTV News.

There are no drugs that help improve failing human memory, a classic symptom of aging. But electric stimulation could change that, Voss said.

"As we get older, that communication between the hippocampus and the rest of its network, so to speak, goes down, and that is associated with aging memory impairment. And what we found in our study at least is TMS … improves the communication between those regions and thereby improves people’s memory ability,” he said.

Researchers in Canada are intrigued by the idea. Jed Meltzer, a scientist at Baycrest Hospital’s Rotman Research Institute in Toronto and psychology professor at the University of Toronto, said years from now the approach may offer benefits to patients with other neurodegenerative disorders, such as dementia.

“What this brain stimulation gives you is the ability to target very specific aspects of the brain, very specific areas. And so unlike giving a drug where it affects the entire brain at once, we can really home in the areas that are affected by the disease,” Meltzer said.

Even so, there are some obvious drawbacks. Studies have yet to prove that the memory-boosting benefits of electric stimulation last longer than a few days.

Meltzer is cautiously optimistic.

"I wouldn’t say that this is a cure for memory decline. We still need to learn a lot more about how much stimulation it actually takes to have a lasting effect,” he said.

“The big questions going forward are how to make it cheap and widely available and more effective than they’ve shown already.”

In the meantime, scientists across the globe are testing different forms of electric stimulation. Aside from TMS, researchers are looking into transcranial direct current stimulation, or tDCS, which uses a small 9-volt battery about the size of a smoke detector that produces electric currents via electrodes placed directly on the scalp or forehead.

A 2015 report by Harvard Women’s Health Watch looked into a large number of studies regarding electric stimulation. The studies touted a range of benefits, including improved math abilities and increased ability to recall lists and patterns.

According to the Harvard report, electric stimulation appears to work best when combined with other memory-boosting methods, such as “learning new systems for remembering names.”

The Harvard report also noted that a few small-scale studies suggested that people with mild Alzheimer’s disease could see improved function through a combination of TMS and cognitive exercises.

For the moment, electric stimulation doesn’t offer any obvious long-term benefits, but Meltzer said the current science is a starting point.

"I think it is a promising advancement,” he said.