The first wave of COVID-19 triggered an increase in psychiatric drug prescriptions in long-term care homes, new data shows, and geriatrics experts warn this puts patients with dementia at risk for further harm from falls, stroke and sedation.

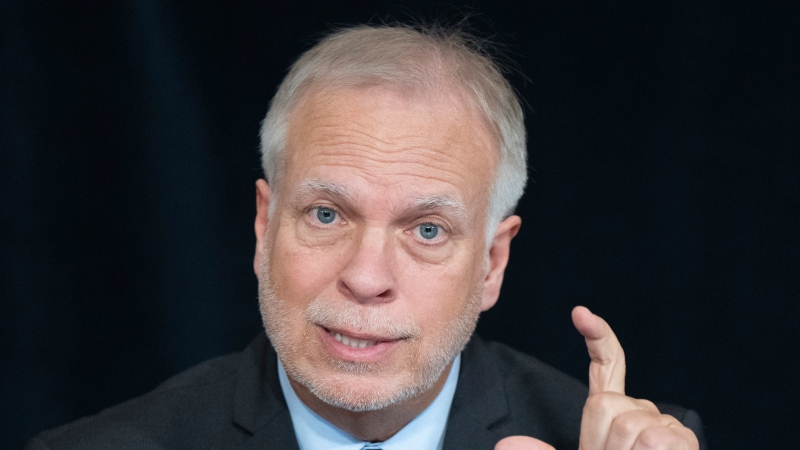

Faced with staff shortages and lockdowns that restrict caregiver visits, nursing homes increasingly fall back on medications to regulate behaviour and manage mental health concerns, says Toronto geriatrician Dr. Nathan Stall.

Prescriptions of antipsychotics, antidepressants, sleeping medications and benzodiazepines all increased between March and September, according to a study of Ontario's 623 licensed nursing homes.

This is an abrupt reversal after years of declining use of sedative medications in seniors, says Stall, who led the study.

Overall, an "additional 1,000 residents are being prescribed antipsychotics who were not on the medication before the pandemic," Stall says. The jump occurred following restrictions on visitors and congregate activities such as dining and recreational groups.

Such "knee-jerk reactions to try and medicate the distress of residents in nursing homes" during the COVID-19 pandemic are a serious concern, Stall said.

He warns that antipsychotics come with a "black-box warning" for the elderly. Stall says they increase the "risk of stroke, falls and all-cause mortality, and are not recommended for frail, older adults," such as those with dementia, who make up about 70 per cent of nursing-home residents in Ontario.

The preliminary figures from the Ontario study were released Monday on medRxiv (pronounced "med archive"), an online preprint server for medical research.

The findings, which have not yet been peer-reviewed, are in line with growing evidence that during the global pandemic, rising numbers of nursing home residents have received sedative medications, such as antipsychotics.

It could take weeks or months for the findings to be peer-reviewed, but Stall believes it is important to get this information out now in the midst of a second wave.

According to a November report in the medical journal The Lancet, a greater proportion of people with dementia in the United Kingdom have been prescribed antipsychotic medication during the pandemic than in previous years.

And in British Columbia, a survey of nursing home residents and their families by the province's seniors advocate published last month found a seven per cent rate of increase in antipsychotic use, and a three per cent rate of increase in antidepressant use during the time of visitor restrictions for COVID.

"This rate of increase is significant and is one indicator of the potential unintended consequences of the visitor restriction policies," the report states.

In Quebec, Nouha Ben Gaied, director of research and development for the Federation of Quebec Alzheimer Societies, says over the last two years, more than 100 nursing homes have taken part in a provincial initiative that promotes non-pharmacological strategies for patients with dementia and reducing antipsychotics. The pandemic halted the program.

With "a very heavy heart," her colleagues turned to chemical and physical restraints to enforce infection-control measures in Quebec's hard-hit nursing homes, Ben Gaied said. "This is not something that they wanted to do, but this was the only solution they had."

Staff reported that not only were physical barriers put up to keep people confined to their rooms, but medications such as antipsychotics, benzodiazepines and other sleeping medications have been used to sedate and restrict the movement of people with dementia in units affected by COVID with the goal of protecting residents from harm.

Such measures fail to uphold a person's dignity, and she says the stigma of dementia can lead to a curtailing of their rights. Care providers in nursing homes often "forget about the rights of people with dementia, but we should empower (residents) instead of saying `you don't have the right to do certain things' … or `this is to protect you."'

Geriatrics experts are concerned that the global pandemic is undoing years of hard-won progress in reducing the use of potentially dangerous and ineffective medications in the elderly and those with dementia.

Stall also sees these trends as indicators of something even more sinister: the pandemic response may have resulted in more mood disorders and behavioural disturbances for people with dementia.

Dr. Fred Mather, president of Ontario Long Term Care Clinicians and the medical director at Sunnyside Home in Kitchener, Ont., explains that unfortunately, not only are medications such as antipsychotics associated with significant side-effects, but they have also been proven ineffective in treating responsive behaviours in dementia.

He characterizes "responsive behaviours" as distressing behaviours, such as hitting or grabbing, exhibited by people with dementia that put themselves or others at risk. The current understanding of these behaviours is that they are not symptoms of dementia, Mather says, but rather, "a form of communication that needs to be addressed about an unmet need."

And unmet needs, such as confusion, loneliness or boredom -- which Stall has seen worsen under strict visitor restrictions and social isolation in Ontario's nursing homes -- are not best treated with medication.

Geriatric psychiatrist Dr. Andrea Iaboni, who practises at the Toronto Rehabilitation Institute and in several nursing homes, notes that "there's no such thing as a medication that will make someone stay in their room -- there's no pill for that."

"If you don't have the capacity to remember that there's a pandemic, or don't have insight into the fact that you might be at risk or that people around you are at risk (of COVID), it becomes very hard to adhere to (infection control) measures," Iaboni says of people living with dementia and cognitive impairment.

She has helped create a social isolation toolkit for long-term care providers to plan for how to best protect residents from the novel coronavirus while preserving a quality of life.

Iaboni says that if medications are used, they need to be monitored very closely, as residents on antipsychotics are "going to be more sleepy or more confused, maybe more unsteady in their gait and more at risk of an adverse event," such as a fall.

While she hasn't seen evidence of widespread use of antipsychotics as chemical restraints, Iaboni says she's getting more referrals for "mental health problems such as depression and even psychotic depression, or the development of delirium or psychosis."

Iaboni described how isolation requirements for residents exposed to or infected with the virus "are kind of like putting them in solitary confinement and under those circumstances, people start to hallucinate, they start to develop delusions" -- which would be an appropriate indication to prescribe an antipsychotic.

Stall says the rising prescription rates found in his research reflect what family caregivers have been telling him and what he has been seeing in his own clinical work: high levels of distress among residents who have been isolated and separated from essential care providers and loved ones.

He says a new approach is needed to address the social and mental-health needs of long-term care home residents.

"I think about my grandmother, about going for a walk around the block. And leaving the residence and going to her children's house to have dinner inside their home. And, you know, we should be able to create more nuanced policies that have a little more balance, that maintain the dignity and well-being of older adults."

--Kaleigh Alkenbrack is a family physician and psychotherapist in St. Catharines, Ont., and a fellow in Global Journalism at the Dalla Lana School of Public Health.