Indian envoy warns of 'big red line,' days after charges laid in Nijjar case

India's envoy to Canada insists relations between the two countries are positive overall, despite what he describes as 'a lot of noise.'

Scientists in the U.K. believe they have discovered the reason why some people experienced the very rare side-effect of blood clots after receiving the AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine.

The findings, published in the journal Science Advances on Wednesday, reveal that a protein found in blood is drawn to a component of the vaccine, which triggers a reaction from the body’s immune system that can result in clots.

The AstraZeneca vaccine, like other viral vector vaccines, uses a safe virus as a “host” to deliver genetic information about the COVID-19 spike protein to the vaccine recipient's cells so that they can build an immune response and create antibodies.

The AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine uses a cold virus from a chimpanzee, also known as a chimpanzee adenovirus, as the delivery system. This is because it cannot make humans sick – and, because they have not been exposed to it before, they will not have antibodies against it.

Viral vector vaccines modify the delivery virus so that it cannot spread, they simply delivers the instructions for the body’s cells.

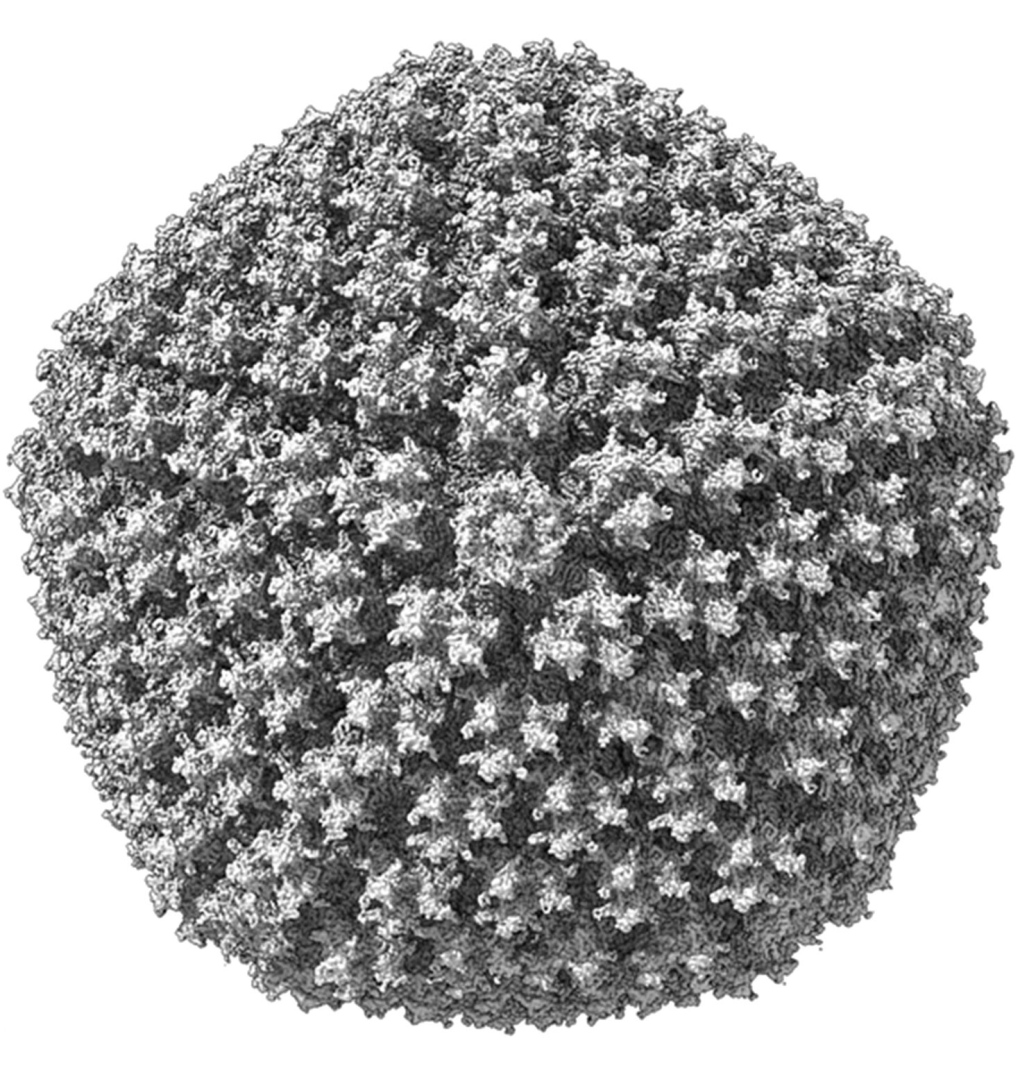

By analyzing the chimpanzee adenovirus used by AstraZeneca with cryo-electron microscopy, which allows for molecular-level details to be seen, researchers found that the adenovirus attracts the blood protein known as “platelet factor 4” to it.

Cryo-electron microscopy involves flash-freezing the study subject and then bombarding them with electrons to produce microscope images of individual molecules. Those are then used to reconstruct the structure of the subject in minute detail.

The cryo-electron microscopy image of the chimpanzee adenovirus, which is less than 100 nanometres across, that delivers the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine. (Science Advances Journal)

The cryo-electron microscopy image of the chimpanzee adenovirus, which is less than 100 nanometres across, that delivers the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine. (Science Advances Journal)

The cryo-electron microscopy image of the chimpanzee adenovirus which delivers the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine. (Science Advances Journal)

Platelet factor 4 is implicated in the origins of another clotting event called heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT), which causes changes to the blood that may cause a clot to form in the blood vessels.

Researchers posit that the body begins to attack the platelets that are attached to the adenovirus, after mistaking it as part of the foreign virus. Then, when antibodies are released into the bloodstream to attack, they clump together with the platelet factor 4 and can form a dangerous blood clot known as vaccine-induced thrombotic thrombocytopenia or VITT.

Because that sequence of events in the body is so specific, it may explain why the development of blood clots after receiving the vaccine is such a rare phenomenon.

The U.K. findings echo a Canadian study conducted by researchers at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ont., and published this July in the scientific journal Nature.

In the Canadian study, researchers analyzed blood samples from five patients with VITT and compared them to blood samples of 10 patients with HIT and 10 samples from healthy individuals.

Looking at the amino acids of the interaction between the VITT antibodies and platelet factor 4 protein, researchers found eight specific amino acids on the platelet protein that were identical to the binding site of HIT, which they believe could explain the similar patterns in how the blood clots form after vaccination.

However the U.K. study was able to render the highest resolution of the adenovirus used in the AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine to date, allowing them to better understand its primary cell attachment proteins and its structure.

VITT has been linked to at least one death in Canada after an Ontario man received the AstraZeneca vaccine in May, and to 73 deaths out of close to 50 million doses of AstraZeneca administered in the U.K.

The Public Health Agency of Canada’s National Advisory Committee of Immunization stopped recommending AstraZeneca’s COVID-19 vaccine as a second dose option after some Canadian recipients reported blood clots in the spring of 2021.

Researchers in the U.K. hope their study findings can be used to improve future vaccines and reduce the risk of blood clots.

-----

With files from CTVNews.ca writer Brooklyn Neustaeter

India's envoy to Canada insists relations between the two countries are positive overall, despite what he describes as 'a lot of noise.'

With Donald Trump sitting just feet away, Stormy Daniels testified Tuesday at the former president's hush money trial about a sexual encounter the porn actor says they had in 2006 that resulted in her being paid to keep silent during the presidential race 10 years later.

The U.S. paused a shipment of bombs to Israel last week over concerns that Israel was approaching a decision on launching a full-scale assault on the southern Gaza city of Rafah against the wishes of the U.S.

Footage from dozens of security cameras in the area of Drake’s Bridle Path mansion could be the key to identifying the suspect responsible for shooting and seriously injuring a security guard outside the rapper’s sprawling home early Tuesday morning, a former Toronto homicide detective says.

A chicken farmer near Mattawa made an 'eggstraordinary' find Friday morning when she discovered one of her hens laid an egg close to three times the size of an average large chicken egg.

Susan Buckner, best known for playing peppy Rydell High School cheerleader Patty Simcox in the 1978 classic movie musical 'Grease,' has died. She was 72.

Accused killer Jeremy Skibicki could have a challenging time convincing a judge that he is not criminally responsible for the deaths of four Indigenous women, a legal analyst says.

A Calgary bylaw requiring businesses to charge a minimum bag fee and only provide single-use items when requested has officially been tossed.

Two Nova Scotia men are dead after a boat they were travelling in sank in the Annapolis River in Granville Centre, N.S., on Monday.

An Ontario man says he paid more than $7,700 for a luxury villa he found on a popular travel website -- but the listing was fake.

Whether passionate about Poirot or hungry for Holmes, Winnipeg mystery obsessives have had a local haunt for over 30 years in which to search out their latest page-turners.

Eighty-two-year-old Susan Neufeldt and 90-year-old Ulrich Richter are no spring chickens, but their love blossomed over the weekend with their wedding at Pine View Manor just outside of Rosthern.

Alberta Ballet's double-bill production of 'Der Wolf' and 'The Rite of Spring' marks not only its final show of the season, but the last production for twin sisters Alexandra and Jennifer Gibson.

A mother goose and her goslings caused a bit of a traffic jam on a busy stretch of the Trans-Canada Highway near Vancouver Saturday.

A British Columbia mayor has been censured by city council – stripping him of his travel and lobbying budgets and removing him from city committees – for allegedly distributing a book that questions the history of Indigenous residential schools in Canada.

Three men in Quebec from the same family have fathered more than 600 children.

A group of SaskPower workers recently received special recognition at the legislature – for their efforts in repairing one of Saskatchewan's largest power plants after it was knocked offline for months following a serious flood last summer.

A police officer on Montreal's South Shore anonymously donated a kidney that wound up drastically changing the life of a schoolteacher living on dialysis.