Scientists at the University of Waterloo are working on a new tool they hope could protect women from HIV infection, and drew their inspiration from a group of Kenyan women who are naturally immune to the virus.

Dr. Emmanuel Ho, a professor in the School of Pharmacy at Waterloo, has designed the device that is meant to mimic what protects a unique group of sex workers in Kenya who have a natural immunity to HIV.

What Ho learned about these women is that they have low levels of activity in their T cells, which are the cells the immune system sends into action whenever a virus enters the body.

Normally, T cells become fighter cells and kill off infecting viruses, but Dr. Ho explains that HIV outwits T cells by corrupting and destroying them.

“HIV says, ‘Hey, you know what? These T cells play an important role. Let me infect them and deactivate them.’ And once there are low level of T cells in the body, that's what leads from HIV infection to AIDS,” he told CTV Toronto.

When T cell levels drop, the body is vulnerable to even the mildest of infections. But if the T cells are “resting” and do not attempt to fight HIV, HIV won’t attempt to destroy them. This state of T cell resting is called being “immune quiescent.”

Ho decided to look at whether there was a way to induce T cell quiescence in women with a medication delivered right at the point of infection in the vagina. Ho decided to try hydroxychloroquine, a drug commonly used to prevent malaria, and to treat rheumatoid arthritis and other autoimmune conditions

“We thought: can a drug similar to hydroxychloroquine that has some kind of immunomodulatory effect, can it maintain or induce this resting T cell state?” Ho said.

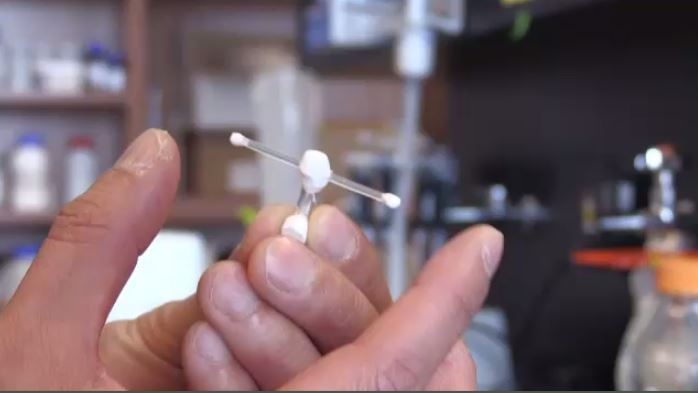

His team decided to test the idea by creating a vaginal implant composed of a hollow tube with two flexible arms to hold it in place. The tube is filled with hydroxychloroquine which is released slowly and absorbed by the walls of the vaginal tract.

The implants were tested in animals and Ho’s team noticed a significant reduction in T cell activation, meaning the vaginal tract demonstrated an immune quiescent state. Their results appear in the Journal of Controlled Release.

Ho says further research will help his team learn whether the implant could be a stand-alone option for preventing HIV or if it could be used in conjunction with other transmission prevention strategies.

But he thinks the implant would be a more reliable system than pills since people tend to forget to take pills. His team hopes to begin clinical trials on humans within the next five years.

With a report from CTV Toronto’s health specialist Pauline Chan