A new report is shedding more light on “alarmingly high” food prices in remote northern Ontario communities, including one First Nation where residents spend more than half of their income on basic nutrition.

The Food Secure Canada report looked at food costs on three reserves in northeastern Ontario: Moose Factory, Fort Albany and Attawapiskat. It found that on-reserve households in Fort Albany need to spend 56 per cent of their income on a basic nutritious diet.

Although current income data was not available for Attawapiskat and Moose Factory, the report said “a reasonable assumption must be made” that people in those communities also spend at least 50 per cent of their income on groceries.

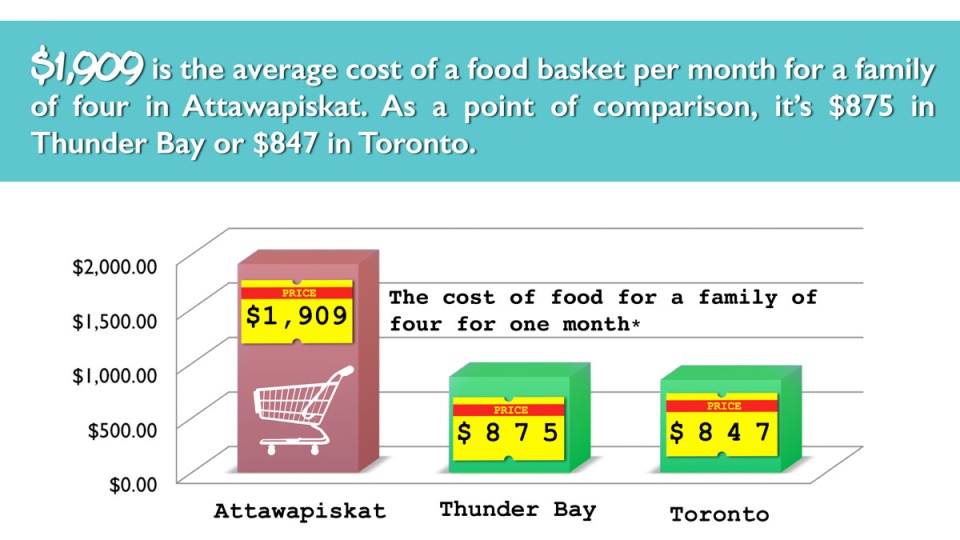

In Attawapiskat, the average cost of a monthly food basket for a family of four was $1,909 in June 2015, compared to $847 in Toronto. Both Attawapiskat and Fort Albany, where the monthly food basket was priced at $1,831.76, qualify for the federal government’s Nutrition North Canada subsidy program, which aims to make fresh food more affordable in northern communities.

“I think this report highlights the wildly inappropriate assistance levels that exist in Ontario,” Joseph LeBlanc, a Food Secure Canada board member, told CTV News Channel on Monday.

“It really showcases the reality of purchasing a healthy diet in remote communities and how inaccessible it really is.”

For example, a 1.3-kilogram bag of apples in Attawapiskat cost $8. A 4.5-kilogram bag of potatoes in Fort Albany cost nearly $10.

Other examples include:

- $8.99 for a 680-gram box of Cornflakes in Moose Factory

- $10.65 for a 2.5-kilogram bag of all-purpose flour in Fort Albany

- $20 for a kilogram of ground beef in Moose Factory

LeBlancsaid one of the biggest issues lies with government-approved suppliers and retailers associated with the controversial Nutrition North program, which was heavily criticized by the federal auditor general in his 2014 fall report.

In many cases, a northern community’s only grocery store is part of a chain that holds a virtual monopoly on the supply of perishable food items, Food Secure Canada says.

“In doing that, they constrain the buying power of the consumer and really, community initiatives that had been attempted to be developed to address this,” LeBlanc said.

Other factors that contribute to high food prices in the North include higher transportation, fuel and maintenance costs and a complex food distribution system that is often restricted to limited deliveries by plane, the report said.

The report also notes that out of 32 remote reserves in Ontario, only eight are eligible for a full Nutrition North subsidy.

“The Nutrition North Canada subsidy program, while important, does not lower the cost of food in northern communities to affordable levels,” the report says. It calls on federal and provincial governments to “make access to nutritionally adequate and culturally appropriate food a basic human right in Canada.”

The Liberals’ 2016 Budget included $64.5 million over five years and $13.8 million per year ongoing to expand Nutrition North “to support all isolated communities.”

LeBlanc said the larger issues facing remote northern communities, such as high suicide rates, poor education and health outcomes, can all be linked to food insecurity.

“All of these are symptomatic of a broken food system and a broken economy,” he said.

Arlen Dumas, Chief of Mathias Colomb Cree Nation in northern Manitoba, agreed that expensive food is linked to health issues like diabetes.

Even where produce is available, “you’re more likely to go purchase something that comes in a can or a package because it’s less expensive,” he said.

“There aren’t a lot of jobs, a lot of people are on assistance,” he added. “It’s very difficult when those are the types of prices you have to pay for food.”

With a report from Manitoba Bureau Chief Jill Macyshon