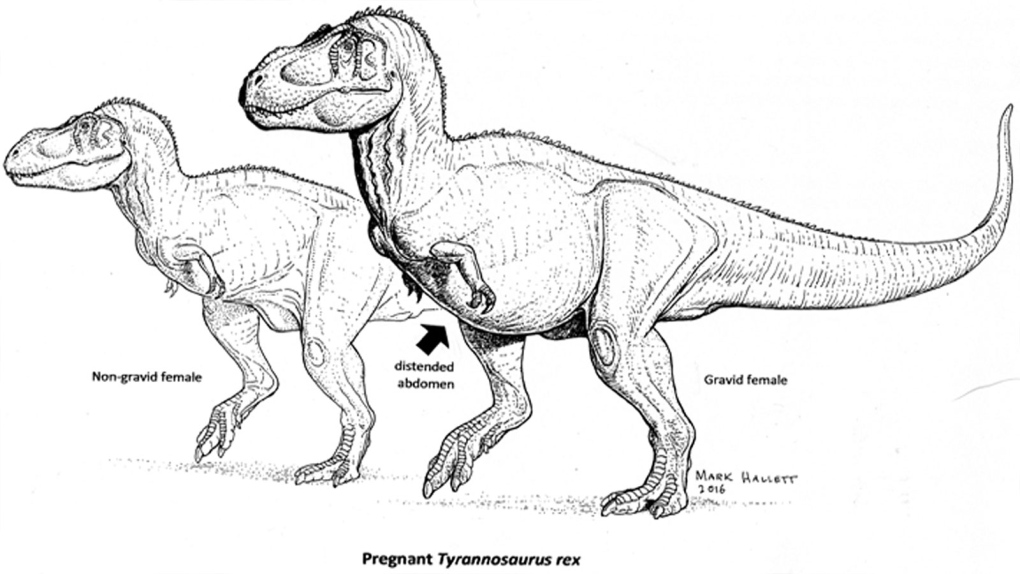

Researchers have found the remains of a pregnant Tyrannosaurus rex, a major discovery that they say could shed light on the differences between male and female meat-eating dinosaurs.

Scientists from North Carolina State University and the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences confirmed the discovery on Tuesday.

According to the researchers, the pregnant dinosaur roamed what is now Montana about 68 million years ago.

In a university press release, study co-author Lindsay Zanno said the dinosaur discovery could provide answers to some of paleontology's biggest questions.

"It's a dirty secret, but we know next to nothing about sex-linked traits in extinct dinosaurs," she said. "Dinosaurs weren't shy about sexual signalling, all those bells and whistles, horns, crests and frills, and yet we just haven't had a reliable way to tell males from females."

Scientists were able to confirm the Tyrannosaurus rex's pregnant condition and gender by examining her femur, or thigh bone, and looking for material known as "medullary bone."

Today, medullary bone is found in female birds before and after they lay eggs.

This type of bone is chemically different from regular bones, the university press release explains, because it helps birds shell their eggs.

And because the Tyrannosaurus rex belonged to the same dinosaurian group that includes modern birds, scientists theorized that pregnant dinosaurs may also form medullary bone.

North Carolina State Paleontologist Mary Schweitzer first found what she believed to be Tyrannosaurus rex medullary bone in 2005. But it wasn't until more recently that scientists were able to chemically analyze the material and confirm what it was.

"All the evidence we had at the time pointed to this tissue being medullary bone," Schweitzer says, "but there are some bone diseases that occur in birds, like osteopetrosis, that can mimic the appearance of medullary bone under the microscope."

Using a series of tests, the scientists compared the tyrannosaurus bone to medullary tissue from ostrich and chicken bones.

In the end, the findings confirmed that the dinosaur was pregnant around the time of her death.

"This analysis allows us to determine the gender of this fossil, and gives us a window into the evolution of egg laying in modern birds," Schweitzer said.

According to Zanno, the important find could lead to further discoveries and a better understanding of how dinosaurs reproduced.

In the future, Zanno said CT scans may help scientists in their search for other specimens with medullary bone.

"Just being able to identify a dinosaur definitively as a female opens up a whole new world of possibilities," she said. "Now that we can show pregnant dinosaurs have a chemical fingerprint, we need a concerted effort to find more."